The late-great Stan Winston was responsible for some of the most memorable monsters in modern cinema: the endoskeleton robotic killing machine in The Terminator (1984), the ferocious Queen Alien in Aliens (1986), the alien that hunts Arnold Schwarzenegger in Predator (1987), and, of course, the dinosaurs in Jurassic Park (1993). I don’t know where the Kothoga from The Relic (1997) fits in the pantheon of Winston’s creatures but it is one of my favorites of his creations. Based on the best-selling horror novel of the same name by Douglas Preston and Lincoln Child, The Relic was a modest hit at the box office and predictably received mixed reviews by critics but remains one of my favorite creature features. Peter Hyams’ film has no other ambitions other than to tell an entertaining, things-go-bump-in-the-night story and does so in refreshingly no-nonsense fashion.

A ship arriving from Brazil is stopped by the Coast Guard in Lake Michigan and they find out that everybody on board has been killed. This doesn’t sit too well with Chicago police detective Vincent D’Agosta (Tom Sizemore) who has been put in charge of the investigation. Meanwhile, at the Museum of Natural History in Chicago, evolutionary biologist Dr. Margo Green (Penelope Ann Miller) is trying desperately to get a grant so that she and her team can continue their work. However, a co-worker (Chi Moui Lo) is doing his best to steal her grant away to fund his own work. They both get a chance to impress a crowd of the city’s wealthiest patrons at the gala premiere of a new exhibit. As luck would have it, D’Agosta will also be attending as he investigates a gruesome murder that occurred at the museum the night before. Could it be an ancient creature known as the Kothoga which, legend has it, is the offspring of South America’s answer to Satan? It seems that it was in one of the crates on the ship from Brazil and has now decided to snack on some bluebloods during the gala. It’s up to D’Agosta and Green to stop this creature.

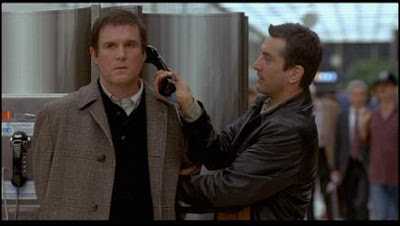

Tom Sizemore brings a solid, matter-of-fact vibe to his character that feels like he carried it over from his role in Heat (1995). D’Agosta isn’t some wisecracking cop trying to make the moves on Penelope Ann Miller’s cute biologist. He’s interested only in solving the murder. However, he does have one distinctive trait: he’s superstitious. Sizemore manages to insert it here and there throughout the film without belaboring it to the point of being painfully obvious. I like that he gives D’Agosta a genuinely inquisitive nature. He’s not some burn out or a stereotypical loose cannon but a guy good at his job. He’s also savvy enough to realize that the murder at the museum hasn’t been done by your garden variety psycho and doesn’t let anybody, not some jerk rent-a-cop or even the condescending mayor of the city, distract him from his investigation.

Sizemore enjoyed a good run in the 1990s, appearing in films like Natural Born Killers (1994), Heat, and Saving Private Ryan (1998) before a myriad of personal problems burned a lot of bridges in Hollywood and relegated him to direct-to-video hell. He’s quite good in The Relic, his first leading man role and the cheap shots by critics back in the day that blasted him as resembling an overweight George Clooney were unfair. Sizemore certainly has the presence and the intensity to be a credible leading man and his blunt cop anticipates a similar one he played in the short-lived television show, Robbery Homicide Division. He was attracted to The Relic because he finally got to play the male lead in a film: “I had the responsibility of pushing the narrative forward.”

Penelope Ann Miller is just fine as the plucky heroine and thanks to action producer Gale Anne Hurd (The Terminator, Aliens) Margo Green is smart and proactive. She’s no damsel in distress and is actually quite resourceful, which is a refreshing change in a film like this one. It is nice to see characters using their intelligence in a horror film. For example, at one point D’Agosta takes Green to her lab so that she can figure out what the creature is and how to stop it. He opens up a little bit and tells her why he’s so superstitious. It’s a brief scene but it gives us some good insight into these characters. In the ‘90s, Miller made a significant push to be regarded as an A-list leading actress in high profile studio films like Awakenings (1990), Carlito’s Way (1993), The Shadow (1994), and The Relic, but none of them set the world on fire in terms of box office and she never became much of a critic’s darling either. I always found her kind of annoying and often miscast (see Carlito’s Way) with the notable exception of The Freshman (1990) in which she was perfect as Marlon Brando’s spoiled daughter. Before The Relic, Miller had not done a horror film but was drawn to director Peter Hyams’ desire to have a strong and smart female lead.

Hyams does a decent job establishing The Relic’s premise and introducing the characters, all the while building towards the climax: gala night at the museum with the creature on the rampage. He cuts between the guests trying to escape the museum while D’Agosta and Green attempt to stop the monster. Journeyman director Hyams epitomizes meat and potatoes filmmaking with his straightforward camerawork devoid of any distinctive style. Guillermo Del Toro he is not but that’s okay. Hyams keeps things moving along while plugging in the requisite jolts at certain moments throughout the film. Once the power goes out in the museum, he uses the darkness to tease us with glimpses of the creature until the full reveal during the final showdown. If I had one complaint it is that he relies too much on the dark and sometimes it is hard to tell what is happening.

Also of note is the solid supporting cast including Linda Hunt as the pragmatic director of the museum and James Whitmore as Green’s kindly old colleague and mentor. Genre veteran Clayton Rohner (G vs E) has a nice role as the junior detective working with D’Agosta. He’s put in charge of taking the mayor and a few others to safety. It’s not a flashy role but he does the best with what he’s given.

The original novel was written by Lincoln Child and Douglas Preston, an ex-journalist and former public relations director for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Because their book portrayed the museum’s administration in an unflattering light, they turned down the film’s producers’ request to film there. Paramount Pictures, the studio backing the production, even approached the museum and offered them a seven figure amount to film there but ultimately the administration was worried that a monster movie would scare kids away from the museum. So, the filmmakers were faced with a problem as only museums in Chicago and Washington, D.C. resembled the one in New York. Fortunately, the Field Museum in Chicago loved the film’s premise and allowed the production to shoot there. In addition to shooting on location in Chicago, a set was built in Los Angeles of a tunnel flooded with water for a sequence later on in the film. Sizemore and many of the cast spent most of the shoot either damp, cold or soaking wet. He caught the flu twice and the production shut down briefly when Hyams became too sick to work.

Hyams reviewed makeup artist Stan Winston’s early drawings of the Kothoga and his only suggestion was to make the monster more hideous looking. The director suggested certain invertebrates for inspiration and Winston came up with an arachnoid outline for the creature’s face. He and his team made three creatures with two people moving the heads and people on the side working the electronics to move the arms, claws, mouth, and so on. In the scenes where the creature is running or jumping, a computer-generated version was used.

Film critics of the day gave The Relic negative to mixed reviews. In his review for the Washington Post, Richard Harrington wrote, “the DNA speculation that supposedly fuels the plot feels right out of Beavis and Butt-head.” Entertainment Weekly gave it a “C+” rating and wrote, “If you can stagger around the plot holes (how'd a Brazilian cargo ship with a dead crew get to Lake Michigan?), the last 30 minutes are pure, dumb monster-movie fun.” In his review for the Globe and Mail, Geoff Pevere wrote, “The movie is a shameless cut-and-paste of a half-century of bogeyman-movie clichés.” USA Today gave the film two out of four stars and Susan Wloszczyna wrote, “amid caviar-quality Oscar contenders, it’s a palate cleanser – if you have a taste for explicit decapitations and loopy macabre humor.” However, Roger Ebert gave the film three out of four stars and wrote, “All of this is actually a lot of fun, if you like special effects and gore. To see this movie in the same week as the hapless and witless Turbulence is to understand how craft and professionalism can let us identify with one thriller heroine and laugh at another.” In his review for The New York Times, Stephen Holden wrote, “Yes, we've seen it all before. But The Relic proves that the hoariest clichés, when stirred together with enough money, shaken vigorously and artfully lighted, can still make the adrenaline surge.”

Ultimately, The Relic is barely a notch above the cheesy creature feature films that popular the SyFy Channel but so what? The dialogue at times is kinda clunky and most of the characters never go beyond their stereotypes but that’s what you get when you have four screenwriters credited with writing the damn thing. That being said, the film is relatively devoid of narrative fat, which I like, Stan Winston’s monster looks pretty cool, there’s decapitations a-go-go for the gorehounds, Sizemore plays a gruff, superstitious cop, and Miller’s pretty scientist gets to kick ass. The Relic is a well-oiled thrill machine that delivers on its promise of providing a rollercoaster ride. What more do you want from this kind of film?

SOURCES

Cohen, David S. “Locked in

Realm of Monstrous Terror.” South China Morning Post. March 16, 1997.

Slotek, Jim. “They Created a

Monster.” Toronto Sun. January 12, 1997.

Williams, Sue. “Actor

Immerses Himself in the Part.” The Australian. May 1, 1997.