There’s

only one thing everyone can agree on regarding the assassination of American

President John F. Kennedy: he was killed on November 22, 1963. Everything else

around this watershed event in American history has been subject to intense

debate and one that has provoked people to question their own beliefs and those

of their government. Yet, for such a highly publicized affair there are still

many uncertainties that surround the actual incident. Countless works of

fiction and non-fiction have been created concerning the subject, but have done

little in aiding our understanding of the assassination and the events

surrounding it. Oliver Stone's film JFK

(1991) depicts the events leading up to and after the assassination like a

densely assembled puzzle complete with jump cuts and multiple perspectives.

Stone’s film presents the assassination as a powerful event constructed by its

conspirators to create confusion with its contradictory evidence, to then bury

this evidence in the Warren Commission Report, which in turn manifests multiple

interpretations of key figures like triggerman Lee Harvey Oswald. JFK offers a more structured examination

of the conspiracy from one person's point of view where everything fits

together to reveal a larger, more frightening picture implicating the most

powerful people in the United States government.

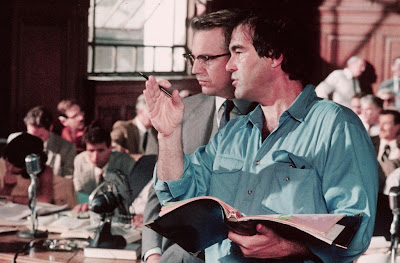

Stone’s

film filters an examination of two conspiracies, one to kill the President and

one to cover it up, from one person's point of view — Jim Garrison (Kevin

Costner) — the New Orleans District Attorney who then assembles all the

evidence at his disposal to deliver a powerful and persuasive case for a

conspiracy to kill Kennedy. Stone saw his film consisting of several separate

films: Garrison in New Orleans against Clay Shaw (Tommy Lee Jones), a key

figure in the assassination, Oswald’s (Gary Oldman) backstory, the recreation

of Dealey Plaza, and the deep background in Washington, D.C. JFK is the mother of all paranoid

conspiracy thrillers, the ultimate one man against the system film with

Garrison taking on the establishment, attempting to uncover one of the most

nefarious plots in history. It created such profound shockwaves in the real

world that Stone was criticized and vilified in the press.

“God, I’m

ashamed to be an American today,” says Garrison when he finds out that Kennedy

has been shot and we see people in the bar he’s in applaud the man’s death.

Stone and cinematographer Robert Richardson desaturate the colors in the 1963

scenes, which creates a somber tone as the country reacts to the Kennedy

assassination.

This

encounter provokes Garrison to go through all the volumes of the Warren

Commission Report and find that, “Again and again credible testimony ignored,

leads are never followed up, its conclusions selective, there’s no index. It’s

one of the sloppiest, most disorganized investigations I’ve ever seen.” He

concludes that this was by design: “But it’s all broken down and spread around

and you read it and the point gets lost.” He continues to dig deeper and the

testimony of Lee Bowers (Pruitt Taylor Vince), who hints at another shooter on

the grassy knoll, is the final straw.

Garrison

walks the streets of New Orleans with two of his investigators Lou Ivon (Jay O.

Sanders) and Bill Broussard (Michael Rooker), recounting Oswald’s time in the

city in a brilliantly written and performed monologue (one of many). He points

out to them that Oswald, a supposed communist sympathizer, spent his time in

the heart of the government’s intelligence community with the FBI, the CIA, the

Secret Service and the Office of Naval Intelligence all within spitting

distance of each other. As Garrison tells them, “Isn’t this seem to you a

rather strange place for a communist to spend his spare time?” He tells them that

they are going to reopen the investigation of the Kennedy assassination and

this is where the film really begins to gather narrative momentum.

Garrison starts interviewing people that had some link to the conspirators, namely Clay Bertrand a.k.a. Clay Shaw, which gives Stone the opportunity to trot out a parade of name actors such as Jack Lemmon, John Candy and Kevin Bacon to portray a very colorful cavalcade of characters. The interviews paint a vivid picture of David Ferrie (Joe Pesci) and Shaw working with Oswald. Stone uses Bacon and Lemmon to detail the conspiracy on a local level, expounding a ton of expositional dialogue brilliantly, while Candy’s hipster lawyer conveys the danger Garrison faces digging into the murder of the President.

Garrison starts interviewing people that had some link to the conspirators, namely Clay Bertrand a.k.a. Clay Shaw, which gives Stone the opportunity to trot out a parade of name actors such as Jack Lemmon, John Candy and Kevin Bacon to portray a very colorful cavalcade of characters. The interviews paint a vivid picture of David Ferrie (Joe Pesci) and Shaw working with Oswald. Stone uses Bacon and Lemmon to detail the conspiracy on a local level, expounding a ton of expositional dialogue brilliantly, while Candy’s hipster lawyer conveys the danger Garrison faces digging into the murder of the President.

Stone presents a series of lengthy dialogue-driven scenes conveying an incredible amount of information in palatable fashion by having recognizable actors as his mouthpieces while dynamically shooting and editing them. He has a character spout a fact or theory and then cuts to a dramatic reenactment that depicts it in black and white and/or different film stock, often blurring the line between fact and fiction, which is the point. In a case as complex as this it is hard to discern which is which as witness testimony conflicts one another making it difficult to make sense of it all.

Stone’s portrayal of Garrison is reminiscent of Jimmy Stewart in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939) – the last honest man in government – and he tries to temper this by showing the trouble he faces at home as his wife (Sissy Spacek) complains that he’s never around anymore and that he cares more about the Kennedy assassination than his own family. She is the film’s weakest character whose sole purpose, initially, is to provide strife on the home front. Stone then has her come around to her husband’s way of thinking after he tearfully tells her late one night that Robert Kennedy has been shot and killed. She admits he was right all along and they make love in a scene that is unnecessarily maudlin. These scenes feel shoehorned in and take away from the main thrust of the film. Stone is on more comfortable ground when he returns to more familiar turf as we see the press arriving in droves to Garrison’s office, making it impossible for he and his team to get any work done. Funding for his office has dried up and he is forced to use his own savings to keep the investigation going. We also see infighting among his staff and Ivon and Broussard butt heads as we see the latter scared off the case.

X posits that Kennedy was killed because he wanted to break up the CIA, make peace with Russia and end the Vietnam War, which not only pissed off a lot of powerful people but would cost a lot of money as he tells Garrison, “The organizing principle of any society, Mr. Garrison, is the war. The authority of the state over its people resides in its war powers.” He encourages Garrison to “come up with a case. Something. Anything. Make arrests. Stir the shitstorm. Hope to reach a critical mass that’ll start a chain reaction of people coming forward. Then the government’ll crack. Remember, fundamentally, people are suckers for the truth.” This is the film’s idealistic mission statement. Judging from the critical reaction towards the film, Stone certainly succeeded in stirring up the shitstorm and in the court of public opinion he helped reshape the perception of the Kennedy assassination.

While attending the Latin American Film Festival in Havana, Cuba, Stone met Sheridan Square Press publisher Ellen Ray on an elevator. She had published Jim Garrison's book On the Trail of the Assassins. Ray had gone to New Orleans and worked with Garrison in 1967. She gave Stone a copy of Garrison's book and told him to read it. He did and quickly bought the film rights with his own money. The Kennedy Assassination had always had a profound effect on his life and he eventually met Garrison, grilling him with a variety of questions for three hours. The man stood up to Stone's questioning and then got up and left. His hubris impressed the director.

In 1989, Stone met with the three top Warner Bros. executives – Terry Semel, Bob Daly, and Bill Gerber – who had been interested in his work for some time. At the time, Stone was trying to make a film about Howard Hughes but Warren Beatty owned the rights. Stone then pitched JFK to them in 15-20 minutes: “I told them I wanted JFK to be a movie about the problem of covert parallel government in this country and deep political corruption.” Semel remembers Stone asking them, “’Are you concerned politically? Would it affect your company? Are there negative reasons why you wouldn’t do it?’ My immediate reaction was, ‘No, we should do it.’ If it’s entertaining and it’s intriguing, a great murder mystery about something we all cared about and grew up thinking about, why not?” A handshake deal was done and the studio agreed to a $20 million budget.

Filming was going smoothly until several attacks on the film in the press surfaced in the mainstream media including the Chicago Tribune, published while the film was only in its first weeks of shooting. Five days later, the Washington Post ran a scathing article by national security correspondent George Lardner entitled, "On the Set: Dallas in Wonderland" that used the first draft of the JFK screenplay to blast it for "the absurdities and palpable untruths in Garrison's book and Stone's rendition of it.” The article pointed out that Garrison lost his case against Clay Shaw and claimed that he inflated his case by trying to use Shaw's homosexual relationships to prove guilt by association. Other attacks in the media soon followed. However, the Lardner Post piece stung the most as he had stolen a copy of the script. Stone recalls, "He had the first draft, and I went through probably six or seven drafts.”

The film throws many characters at us and it is easier to keep track of them by identifying them with the famous person that portrays them. Stone was evidently inspired by the casting model of a documentary epic he had admired as a child: “Darryl Zanuck's The Longest Day (1962) was one of my favorite films as a kid. It was realistic, but it had a lot of stars ... the supporting cast provides a map of the American psyche: familiar, comfortable faces that walk you through a winding path in the dark woods.” Future biopics with sprawling casts, like The Insider (1999), and Good Night, and Good Luck (2005), and The Good Shepherd (2006) would use this same approach.

SOURCES