For fans of action films from the 1980s and early 1990s, it has always been a pipe dream to see their favourite action stars team up or, better yet, battle each other. Think of it as the cinematic equivalent of fantasy football. With The Matrix (1999), the heyday of muscle-bound action stars like Sylvester Stallone was well and truly over as more normal-looking (physique-wise) actors, with the aid of cutting edge CGI, started doing their own stunts. Former marquee stars like Jean-Claude Van Damme and Steven Segal were relegated to direct-to-home video limbo.

However, over time, people began to look back at that era of action films with nostalgia and Stallone wisely capitalized on it by resurrecting two of his most popular characters, Rambo and Rocky, to critical acclaim and respectable box office. The success of those films culminated in Stallone’s penultimate film, The Expendables (2010). Using his rejuvenated clout and reputation, he cast veteran action stars like Dolph Lundgren and Jet Li, bad boy character actors Mickey Rourke and Eric Roberts, and ultimate fighters and professional wrestlers like Randy Couture and Stone Cold Steve Austin. The real coup for Stallone was coaxing two of the other popular action stars from the ‘80s, Arnold Schwarzenegger and Bruce Willis, to appear in the same scene with their fellow Planet Hollywood owner. The end result is an action film fan’s wet dream.

Barney Ross (Sylvester Stallone) is the leader of an elite group of mercenaries and, in a nice nod to current events, we are introduced to them wiping out a gang of Somalia pirates with plenty of cheeky one-liners, swagger and ultra-violence, including a cool bit where the good guys eliminate some baddies via night vision. Soon afterwards, the enigmatic Mr. Church (Bruce Willis) hires Ross and his crew to take out a ruthless dictator who controls a small, South American country. It turns out that the dictator is just a puppet for James Munroe (Eric Roberts), an ex-CIA operative now corrupt businessman. Ross and his crew of four men are forced take on a small army. The odds sound about right and much carnage ensues.

The cast of The Expendables is uniformly excellent. Mickey Rourke shows up as the guy who fixes Stallone and his gang up with jobs and we get a nice scene where the recent Academy Award nominee, in all of his Method acting glory, banters with Stallone and Jason Statham. Bruce Willis, complete with his trademark smirk and steely-eyed stare, plays the mysterious Mr. Church. Stallone shares a scene with him and Arnold Schwarzenegger that is the action film equivalent of the famous scene between Robert De Niro and Al Pacino in Heat (1995) – an understated meeting between legendary movie stars sharing the same frame. Eric Roberts gets to play a deliciously evil scumbag with just the right amount of suave menace complete with slicked-back hair and expensive suits.

All of the action stars get a chance to strut their stuff with Stallone and Statham getting the bulk of the film’s screen-time as if the former was symbolically passing the torch to the latter. One of the film’s most pleasant surprises is Dolph Lundgren as a psycho junkie ex-member of the Expendables who ends up working for the bad guys because Ross didn’t approve of his sadistic killing methods. Lundgren even gets a very cool fight scene with Jet Li.

There hasn’t been a decent men-on-a-mission film (a la Dirty Dozen) in some time. Inglourious Basterds (2009) could have been that film but Quentin Tarantino mutated it into something uniquely his own. Stallone goes for a meat and potatoes approach with The Expendables that has a refreshing old school feel to it. It has everything you could want from a film like this: bone-crunching violence, tough guys cracking wise, lots of earth-shattering explosions, and bad guys you love to hate. For fans of ‘80s action films, this is a dream come true and one hell of a fun ride.

Special Features:

There is an audio commentary by actor/director Sylvester Stallone. He talks about how he established his character and his crew visually with very little dialogue. He also defends the sparseness of dialogue against criticism that it wasn’t very well-written. Stallone praises Mickey Rourke’s performance and how he only had the actor for 48 hours because he was making Iron Man 2 (2010) at the time. Naturally, Stallone talks about the logistical nightmare of getting Arnold Schwarzenegger and Bruce Willis to have time to do their scene together. Stallone speaks eloquently about the nuts and bolts aspects of making the film and what his intentions were for a given scene.

“Before the Battle – The Making of The Expendables” is an excerpt from an upcoming feature-length documentary called Inferno: The Making of The Expendables that is on the Blu-Ray version. He narrates over behind-the-scenes footage about how The Expendables came together. He talks about his motivation behind casting all these famous action stars and athletes. We see Stallone take all kinds of physical punishment, including a nasty injury as the result of a fight scene with Steve Austin.

There is a deleted scene which is just a bit of extra footage early on where Dolph Lundgren tells a bad joke needlessly reinforcing the craziness of his character. Yeah, we get it.

“Gag Reel” is an amusing blooper reel of the cast flubbing their lines.

Finally, there is a theatrical trailer, T.V. spots and posters.

"...the main purpose of criticism...is not to make its readers agree, nice as that is, but to make them, by whatever orthodox or unorthodox method, think." - John Simon

"The great enemy of clear language is insincerity." - George Orwell

Tuesday, November 30, 2010

Wednesday, November 24, 2010

Home for the Holidays

Christmas holiday movies are a dime a dozen but how many Thanksgiving movies are there? Sure, many are set during this holiday but Home for the Holidays (1995) is the Thanksgiving movie. Director Jodie Foster captures the hassle and the horror of traveling during the holidays and presents an instantly relatable premise: going home for Thanksgiving dinner and having to put up with your relatives. Everyone has been stuck next to that annoying person on a long plane ride or have had to deal with a crowded airport or stuck in bumper-to-bumper traffic. Everybody has a Thanksgiving history and stories that go with it. Home for the Holidays collects several of these stories into one entertaining movie.

The film really comes to life when Robert Downey Jr. as Claudia’s gay brother Tommy arrives with his business partner, Leo “Go” Fish (Dylan McDermott) in tow.Downey Downey Downey

Holiday movies are like Madlibs: they present a structure and archetypes for you to impart your own experiences. Home for the Holidays contains every archetypal character so that you can identify with at least one if not many of the characters. Richter’s script perfectly captures the dysfunctional family that everyone experiences on some level, like how parents know just what to say to get under your skin. The dialogue is idiosyncratic yet very familiar and memorable, especially everything Downey

Foster sets up an idealistic façade but balances it with a realistic depiction of the family dynamic. Richter’s script nails the interplay between retired parents and how they constantly nag each other but really do love one another. And there are the little details that ring true, like how Claudia’s mother makes lists of things to get or do. Sure enough, by dinner time there’s a big blow out argument as old grudges come to the surface. The friction between Tommy and Jo Ann echoes those old arguments that we’ve all had with siblings when one was eight years old and then comes bubbling to the surface whenever you get together with them, no matter how much time has passed. Regardless of all the bad mojo – Tommy having been secretly married to his boyfriend (Chad Lowe), Claudia guilty over being fired and Jo Ann’s bitter resentment with her two free-spirited siblings – coming together for dinner will, they hope, resolve some of these issues. It is a moment where the film gets serious as real issues and true feelings are addressed but it is consistent with what came before and doesn’t take you out of the film. Like real life, some issues are resolved and some aren’t. According to Foster, “At no point did I want the comedy so raucous and exaggerated that you could not believe in it. I wanted people to be able and look at it and say, ‘This is life.’”

Home for the Holidays is not a straight-out comedy because it does have its moments of reflection and even a melancholic tinge of nostalgia. One of its underlying themes is the old chestnut that the more things change, the more we want them to stay the same. That is what makes this film so good. These characters will always be there for us to revisit and enjoy time and time again. Foster’s film has a timeless quality that allows it to endure and hold up to repeated viewings. No matter how much you’ve changed, you revert to your old self when you come home for Thanksgiving.

SOURCES

Claudia Larson (Holly Hunter) is having the worst Thanksgiving ever. She has just been fired from her job, made out with her 60-year-old boss and found out that her daughter Kit (Claire Danes) is going to have sex for the first time. To add insult to injury, Claudia is going to spend Thanksgiving with her parents. Her mother (Anne Bancroft) reads Dear Abby and constantly nags her daughter (“Claudia, I can see your roots.”) while her father (Charles Durning) has selective deafness and weaves in and out of lanes of traffic. The antagonists are represented by Claudia’s sister Jo Ann (Cynthia Stevenson), her boring husband (Steve Guttenberg) and their annoying kids. They provide the friction and conflict, exposing Jo Ann and Claudia’s deep-rooted sibling rivalry issues.

The film really comes to life when Robert Downey Jr. as Claudia’s gay brother Tommy arrives with his business partner, Leo “Go” Fish (Dylan McDermott) in tow.

Geraldine Chaplin, as the family’s eccentric Aunt Glady, all but steals every scene she’s in with her surreal non-sequiters (“Wanna see a really big boil?”) and matches Downey

Castle Rock was originally going to finance the film but canceled and Foster’s own production company, Egg Productions, acquired W.D. Richter’s screenplay. She worked with him on it so that the film ultimately reflects her point-of-view and her own life experience. She spent two weeks rehearsing with her cast before principal photography began in February 1995. Foster used this time to get input from the actors about dialogue – if a scene or speech did not ring true, she wanted to be told. According to Richter, “We all drive each other nuts at holidays like Thanksgiving. I think there is great tragedy and great humor in that. I wanted some sense of a family pulling together in spite of all the problems.”

Foster sets up an idealistic façade but balances it with a realistic depiction of the family dynamic. Richter’s script nails the interplay between retired parents and how they constantly nag each other but really do love one another. And there are the little details that ring true, like how Claudia’s mother makes lists of things to get or do. Sure enough, by dinner time there’s a big blow out argument as old grudges come to the surface. The friction between Tommy and Jo Ann echoes those old arguments that we’ve all had with siblings when one was eight years old and then comes bubbling to the surface whenever you get together with them, no matter how much time has passed. Regardless of all the bad mojo – Tommy having been secretly married to his boyfriend (Chad Lowe), Claudia guilty over being fired and Jo Ann’s bitter resentment with her two free-spirited siblings – coming together for dinner will, they hope, resolve some of these issues. It is a moment where the film gets serious as real issues and true feelings are addressed but it is consistent with what came before and doesn’t take you out of the film. Like real life, some issues are resolved and some aren’t. According to Foster, “At no point did I want the comedy so raucous and exaggerated that you could not believe in it. I wanted people to be able and look at it and say, ‘This is life.’”

The film received mixed reviews but most of the major newspaper critics liked it. In his three and half star review, Roger Ebert praised Foster's ability to direct "the film with a sure eye for the revealing little natural moment," and Downey Downey

SOURCES

Allen,

Tom. "Becoming Jodie Foster." Moviemaker. December 2, 1995.

Bibby,

Patricia. "Jodie Foster Looks Home to Heal." Associated Press.

November 12, 1995.

Hunter,

Stephen. "Foster Feels at Home Adding Fun, Meaning to Holidays Clan."

Baltimore Sun. November 19, 1995.

Kirkland,

Bruce. "Downey to Earth." Toronto Sun. November 6, 1995.

Portman,

Jamie. "Home for the Holidays No

Ordinary Family Film." Montreal Gazette. October 31, 1995.

Young,

Paul F. "Foster Moves Home to Par." Variety. November 19, 1995.

Here's an excerpt from the original short story that the film is based on.

Friday, November 19, 2010

Heat

It seems rather fitting that it took nearly 15 years for Michael Mann to get his ambitious crime epic Heat (1995) made and it has been 15 years since it was unleashed in theaters. After the commercial and critical success of The Last of the Mohicans (1992), he parlayed its commercial and critical success to get his pet project made. He was able to cast legendary actors Robert De Niro and Al Pacino as the leads in what would be their first the on-screen appearance together in a film (they were in The Godfather: Part II but never appeared in the same scene). Mann returned to a 1986 draft of a screenplay that had originated before he made The Jericho Mile (1979). He now had a much clearer idea of how he wanted Heat to be structured and decided to expand its scope.

At the core of Heat is the relationship between career criminal Neil McCauley (Robert De Niro) and dedicated cop, Vincent Hanna (Al Pacino). Mann takes the career criminal from Thief (1981) and the intensely dedicated cop from Manhunter (1986) and places them in the same film together with the sprawling metropolis that is Los Angeles as its backdrop. It is a deadly cat and mouse game realized on an epic level. Imagine Stanley Kubrick’s The Killing (1956) but on the scale of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968).

The opening of Heat introduces the two main protagonists, McCauley and Hanna without any dialogue. Mann relies entirely on their actions to illustrate their defining characteristics. McCauley, disguised as a paramedic, steals an ambulance. It is how he does it that is so impressive. He walks through a busy hospital purposefully, taking in everything and touching nothing so that he leaves no clues behind for the police to find later. Within a matter of moments he is gone.

We first meet Hanna as he is making passionate love to his wife, Justine (Diane Venora). From the beginning, Mann shows a sharp contrast between Neil and Vincent’s professional and personal lives. McCauley is all business. His life is devoted to preparing for his next score. Mann remarked in an interview that the character “is not an archetypal ex-convict, who steals mindlessly until he gets busted back. This guy is methodical and good at what he does. He's going to accumulate a certain amount of capital, and then he's going to boogie. He has a doctrine of having no attachments, nothing in his life he can't walk out on in thirty seconds flat.” Hanna is married — albeit in a relationship rife with problems but at least he has some semblance of a personal life. During the course of the film, these two men will switch roles and this will determine their respective fates.

Hanna may have a personal life but it is a relationship in decline. He is on his third marriage and is gradually losing touch with Justine and her daughter, Lauren (Natalie Portman). After Hanna and Justine make love she tries to invite him to breakfast but he brushes her off to hook up with one of his partners. But not before he comes off as a bit of hypocrite. He criticizes Lauren’s real father for being late in picking her up and for standing her up repeatedly in the past, but he hardly pays attention to her or her mother either. This scene also establishes one of Mann’s prevalent themes: the fracture that exists between parents and their children.

Hanna is not in his element in a domestic setting and this becomes obvious when he appears at the crime scene of the armored car heist perpetrated by McCauley and his crew at the beginning of the film. As soon as Hanna walks on the scene he immediately takes control. It is a real treat to see Pacino act out this scene. He dominates it both physically — in the way he gestures and moves around — and verbally, in the authoritative tone that he speaks to the people around him. Pacino displays a confidence of an actor totally committed to his role, which is appropriate considering his character is someone who is completely committed to his profession. With little prompting, Hanna’s subordinates fill him in on the evidence they found and expertly piece together what they think happened. Hanna listens intently, absorbs everything and then quickly analyzes the situation. He assigns specific tasks to his men with all the efficiency of a professional. This is the complete opposite of what we saw him like at home. He barely hears what Justine has to say and briefly acknowledges Lauren’s presence before quickly leaving for work.

If Hanna is all about the verbal side of the professional Mann protagonist, McCauley is the flip side of the same coin. He is the quiet individual who lets his actions speak for him. Mann defines McCauley’s character visually. This is achieved not only in the exciting armored truck heist sequence — the essence of ruthless efficiency but, more significantly, when he returns to his home. Like most Mann protagonists, he lives in a Spartan, empty place. The establishing shot utilizes a blue filter that saturates the frame, with the ocean infinitely stretching out in the background. This is reminiscent of the scene in Manhunter where Graham and Molly make love in their bedroom. However, Mann uses this scene to illustrate that, unlike Hanna, McCauley is a loner, a prisoner trapped in his own empty surroundings. This is further reinforced by a close-up of his handgun; placed on a coffee table. As he walks over to the large windows overlooking the ocean, the gun looms large, upsetting the composition of the frame as it dwarfs McCauley. He is a man dominated by his profession — it defines who he is as a person. The camera pans up and we see him standing in the middle of this large, empty room, the frames of the window acting as bars, metaphorically trapping him.

Mann uses architecture to illustrate McCauley’s personality. His apartment is comprised of large, blank white walls, cabinets with the bare minimum of dishes and very little furniture. There is just enough to make it functional. This simple design is also reflected in his fashion sense: simple gray or black suits with a white dress shirt. According to Mann, this was an important clue to McCauley’s character: “His main job, as he sees it, in the way he’s elected to live his life, is to minimize risk. That’s why he wears gray suits and white shirts—he doesn’t want to have anything about his personal appearance that’s memorable. He’s a gray man, just some figure who moves through the umber of a poorly lit coffee shop. It’s all invisible, and it’s strictly pragmatic.” Like Frank in Thief, Graham in Manhunter, and later, Jeffrey Wigand in The Insider (1999), McCauley is yet another Mann protagonist who is constantly shown to be a solitary figure in an empty room. He claims, at one point, that “I’m alone. I’m not lonely,” but he is a forlorn figure or else he would not feel the need to get involved with Eady (Amy Brenneman).

Heat is different from other crime films in that it goes to great lengths to show how those around these criminals and the police that chase them are affected by what their loved ones do. Most of the relationships are very dysfunctional and none more so than between Chris Sherilis (Val Kilmer), one of McCauley’s crew, and his wife Charlene (Ashley Judd). He gambles away all of the money he makes on scores and this makes her very upset. She tells him, “It means we’re not making forward progress like real grown-up adults living our lives.” They argue and she makes it clear that, for her, it is not about the money but their son, Dominick. She is concerned for his safety and well being. For her role, Ashley Judd met several women who had been prostitutes and were now housewives. Mann located them through the convicts’ wives and ex-cons he had interviewed in his pre-production research. Some of them had turned tricks in their teens and were now middle-aged housewives selling real estate.

This scene of domestic disharmony is paralleled by Hanna’s own problems. When he comes home Justine informs him that she had dinner ready for them four hours ago. She tells him, “Every time I try to maintain a consistent mood between us you withdraw.” He replies, “I got three dead bodies on a sidewalk off Venice Boulevard.” Hanna tries to articulate something resembling an apology but he is unable. This is not good enough for her and she leaves the room leaving him alone and frustrated. The final shot is of him sitting alone watching T.V. Justine, like Charlene, is frustrated with her relationship. Both women are unhappy and not afraid to let their significant others know how they feel. Justine does not understand Vincent’s devotion to his job or his obsession with taking Neil and his crew down and this results in a rift between the two that is not repaired by the film’s conclusion. Both Hanna and Chris are unable to explain themselves to their wives. They may be the best at what they do but their personal lives are a mess.

Up until this point Neil has stayed faithful to his personal credo, “Don't keep anything in your life you're not willing to walk out on in thirty seconds flat if you feel the heat around the corner.” This begins to change when he meets Eady at a coffee shop. Initially, he is guarded and stand-offish — an attitude that comes with his job. But once he realizes that she is genuinely interested in him, he softens somewhat but is still evasive, lying to her about what he does (a salesman) and asking her a lot of questions but offering little information about himself. He gives out only vague details: “My father, I don’t know where he is. I got a brother somewhere.” However, he does offer one interesting insight into his character. As they look out at the city lights of Los Angeles he tells her about his dream: “In Fiji, they have this iridescent algae. They come out once a year in the water … I’m going there someday.” Like Frank’s dream of a family in Thief and Wigand’s vision of seeing his children playing in The Insider, McCauley will be unable to realize his ambitions because of his failure to adhere to his own personal code. His fatal flaw is that he develops feelings for Eady and thereby betraying himself. Mann foreshadows McCauley’s inevitable downfall as a result of this relationship with tragic sounding electronic music that plays while McCauley and Eady kiss.

The film’s centerpiece is undeniably the classic meeting of Pacino and De Niro, on-screen together for the first time in the careers that takes place over coffee at Mantelli's restaurant in Beverly Hills. Although, ironically, Mann edits the scene so that each man is shown in over-the-shoulder shots and we don’t actually see them face-to-face at any time in the scene. This is the moment when both men size each other up and tell each other their personal philosophies. The dialogue between the two men reveals a lot about who they are:

Neil: If you’re one me and you gotta move when I move, how do you expect to keep a marriage?

Vincent: So, then if you spot me coming around that corner, you just gonna walk out on this woman? Not say goodbye?

Neil: That’s the discipline.

Vincent: That’s pretty vacant.

Neil: It is what it is. It’s that or we both better go do something else, pal.

For Mann, the coffee shop scene between De Niro and Pacino is when "every theme and every storyline in the picture winds up in that scene. It's very much the nexus of the film." Mann made sure that nothing distracted from the exchange between these two men. He wanted the place to be as invisible as possible with the “background is as monochromatic and as minimalist as I could get it, because, boy, I did not want anything to take away from what was happening on Al's face and Bob's face.”

It makes sense, then, that these two men understand each other better than they do their wives or girlfriends. They are more open with each other than with their loved ones because there is a mutual respect and bond between them. Over coffee they tell each other their dreams and Neil’s is particularly illuminating: “I have one where I’m drowning. And I gotta wake myself up and start breathing or I die in my sleep.” Vincent asks him, “You know what that’s about?” To which Neil replies, “Yeah, not enough time.” Like Frank in Thief, Neil’s dilemma is that he does not have enough time to do everything he needs to do. Neil is a fascinating variation on Frank’s character in the sense that he too is forced to decide between preserving a relationship and his work but unlike Frank, he wastes too much time deciding on which one to follow. When Neil finally does make up his mind it is too late and he is punished for his indecision.

Heat’s most exciting action sequence is the now famous bank heist scene. Right from the beginning, Mann establishes a quick pace as Neil enters the bank with pulsating electronic music that anticipates what is going to happen. With incredible precision and timing, McCauley and his crew have taken out the guards, have control of the bank and are taking out large quantities of money in under a minute. The music is underplayed but still effective in creating tension during the sequence. Once McCauley and his crew emerge from the bank and Chris fires the first shot, the music stops and the rest of this exciting sequence plays out with no music — only the deafening roar of the guns firing as McCauley and his men try to escape and turn the streets of Los Angeles into a war zone. Mann made sure that the gunshots sounded realistic and went to great pains to make sure he got the right sounds for the machine guns. He said, “There's a certain pattern to the reverberation. It makes you think you've never heard that in a film before so it feels very real and authentic. Then you really believe the jeopardy these people are in.”

Mann alternates between shaky, hand-held cameras and fluid tracking shots with kinetic editing that brilliantly conveys the exciting action that is taking place. One of the reasons why this sequence works so well and comes across as being so authentic is due in large part to one of the technical advisors for the film: Andy McNab, a Special Forces soldier who infiltrated enemy lines in the Persian Gulf War to sabotage SCUD missiles. De Niro gave Mann his copy of Bravo Two Zero, written by McNab. It so impressed the filmmaker that he hired him to train the cast how to shoot guns for two months. McNab worked from a tape of L.A. Takedown, Mann’s T.V. movie rough draft of Heat, to get an idea of what Mann wanted. The actors rehearsed carrying around the weight of the money they would be stealing in the bank heist. De Niro had to practice how he would carry Kilmer once he was shot and how to fire his weapon with one hand.

Before filming the bank heist sequence, Mann and McNab conducted a dry run with the actors on a real bank. De Niro, Tom Sizemore and Kilmer all wore disguises and body armor. Only the bank manager knew what was really going on. A couple of guys covertly videotaped everything from cameras in bags. The sequence was to be shot at the Far East Bank in Los Angeles. Location manager Janice Polley and the producers spent months beforehand meeting with officials of the bank explaining what was involved. Mann and his crew took over the entire financial district of the city every weekend for five weeks. They were allowed to shoot between 6 pm on Friday and 5 am Monday morning. The production shut down 5th street in L.A. and notified hotels and residents within earshot. The bank heist sequence was so authentic that in 1998, two men foolishly tried to copy what was done in the film. They robbed a bank in L.A. and as McNab remembered, they even "delayed the robbery for three days so they could get exactly the same bags as Kilmer had, and they used machine guns, body armor—everything."

The rest of Heat plays out the aftermath and fallout of the bank heist as McCauley ties up loose ends and attempts to escape with Eady before Hanna can catch him. Ultimately, Heat is about choices. Neil’s final choice in the film is also his most crucial. He has to decide whether to stay with Eady or run on his own from Hanna who is now in hot pursuit. However, Neil hesitates too long and this is what ultimately defeats him. He goes against his own personal code and is punished. Hanna does not and is willing to sacrifice his personal life so that he can take McCauley down. The film ends as it began — without dialogue as Hanna tracks Neil down.

The origins of Heat were based in large part from the experiences of an old friend of Mann's, Chuck Adamson. The police officer had been chasing down a high-line thief named Neil McCauley in Chicago in 1963. One day, "they simply bumped into one another. Chuck didn't know what to do: arrest him, shoot him or have a cup of coffee." Heat was also based on another person according to Mann: “Another is a guy I can't really talk about, who's bright, intuitive, and driven, and runs large operations against drug cartels in foreign countries. He's a singularly focused individual and much of the core of Hanna's character comes from him.” From these two sources, Mann created a story that explored the relationship between Neil McCauley, a career criminal and Vincent Hanna, a dedicated cop with very similar approaches to their professions but on opposite sides of the law.

Mann wrote an early draft of Heat in 1979 that was 180 pages and based on real people he knew personally and by reputation in Chicago. He wrote another draft after making Thief with no intention of directing it himself. During a promotional interview for The Keep (1983), Mann talked about making Heat into a film and was still looking for another director to make it. In the late 1980s, Mann tried to produce the film several times and offered it to his friend and fellow filmmaker, Walter Hill but he turned it down. Mann was still not satisfied with the script, which had developed the character of McCauley but Hanna still needed work.

After making The Last of the Mohicans, Mann returned to a 1986 draft of Heat and decided that he would make it himself. He felt that the L.A. Robbery-Homicide division would be an ideal basis for a television show and took his script and “abridged it severely. I abstracted probably something like 110 pages from 180 pages ... so it’s lacking in the sense that it’s not fully developed.” The result was a made-for-television movie entitled, L.A. Takedown. It was an incredibly fast shoot – uncharacteristic for the methodical Mann – with only ten days of pre-production and 19 days of shooting. In comparison, Heat would have a six-month pre-production period and a 107-day shooting schedule. Takedown starred Scott Plank as Hanna and Alex McArthur as Patrick McLaren, the character that became Neil McCauley in Heat, with Michael Rooker, Xander Berkley (who has a small role in Heat), and Daniel Baldwin. It aired on NBC on August 27, 1989 at 9 pm. In many respects, Takedown was another draft of Heat. The director said in an interview, "it had a similar kind of nucleus, which was the rapport between the thief and the cop." In the L.A. Takedown script, McCauley's gang is not fleshed out all that much. The Chris Shiherlis sub-plot does not exist, the bungled bank robbery sting is gone, and Hanna's step-daughter's sub-plot does not exist. NBC was willing to buy the show if Mann recast the lead actor. He refused and the network did not pick it up.

After L.A. Takedown, Mann had a much clearer idea of how he wanted Heat to be structured. "I charted the film out like a 2 hr 45 min piece of music, so I'd know where to be smooth, where not to be smooth, where to be staccato, where to use a pulse like a heartbeat." In 1994, Mann showed producer Art Linson another draft of Heat over lunch and told him that he was thinking of updating it. Linson read it, loved it and agreed to make the film with Mann. On April 5, 1994, Variety announced that Mann was abandoning his James Dean biopic and prepping Heat with Al Pacino and Robert De Niro attached to the project with filming to take place in either Chicago or Los Angeles.

De Niro got the script first and then showed it to Pacino who read it and wanted to be a part of the film. De Niro thought it was a "very good story, had a particular feel to it, a reality and authenticity." To research their roles Mann took Val Kilmer, Tom Sizemore, and De Niro to Folsom prison and interviewed several inmates. Sizemore talked to one career criminal in particular who was a multi-millionaire and “had socked away several million dollars and continued to do it, you know one more score ... The guys we educated ourselves about only do big jobs, they won't do anything under $2 million. It's all true, that's what's amazing,” the actor remembered.

Scouting locations for Heat started in August of 1994 and continued through December with location manager Janice Polley, who had first worked with Mann on Last of the Mohicans. She had a staff of three to four people who went all over Los Angeles to find locations that had not been filmed before — no easy task. Mann let them know the kinds of houses each character would live in according to their income and financial status, the look of the house and the surrounding area. For example, Chris Shiherlis lived in Sherman Oaks, Vincent Hanna lived in Santa Monica, Neil McCauley's house was on the beach in Malibu, and Eady's house was in the Hollywood Hills. Polley did her job: less than 10% of the 85 locations used had previously appeared in a film. Not a single soundstage was used.

It was important for Mann to capture a certain vibe of L.A. It was almost another character in the film. The director remembers, “I wanted to capture basically the way the city felt to me being out in the middle of it at two in the morning or on top of the gas tower or on top of a roof or flying over it with the LAPD helicopters. You know, there’s a glow that it has, it’s unique western.” The most challenging location for Polley to get was Los Angeles Airport, one of the busiest in the country. After much negotiation, permission was given to shoot in a restricted area where the radar towers are located. At the last minute, Polley got a call. The Unabomber had threatened the post office at LAX and the FBI were called in to investigate. A delay in filming would have cost the production thousands of dollars. They met with LAX security and the FBI and it was determined that the area they were going to shoot in was far enough away from any potential danger.

Heat was released on December 15, 1995 in 1,325 theaters, grossing $8.4 million on its opening weekend. The film was a commercial success, grossing $67.4 million in North America and $120 million in the rest of the world for a worldwide total of $187.4 million.

Heat received mostly positive reviews from critics at the time. In his review for Time magazine, Richard Schickel praised Mann’s direction: “An opening sequence that may be the best armored-car robbery ever placed on film. He proceeds to a crazily orchestrated bank heist that goes awry and finishes in a wild firefight on a crowded downtown street that is a masterpiece of sustained invention.” Newsweek magazine’s David Ansen wrote, “Mann’s not interested in good or evil, but in behavior: the choices people make, the internal pressures that can cause the best-laid plans to go awry.” Roger Ebert gave the film three-and-a-half stars out of four and wrote, “It's not just an action picture. Above all, the dialogue is complex enough to allow the characters to say what they're thinking: They are eloquent, insightful, fanciful, poetic when necessary. They're not trapped with clichés.” In her review for The New York Times, Janet Maslin wrote, “The huge, well-chosen cast for Heat attests to Mr. Mann's eye for both esthetic interest and acting talent. Even small roles are so well emphasized that they show these performers off to fine advantage.”

However, in his review for the Washington Post, Hal Hinson wrote, “Ultimately, though, the movie never transcends the limitations of its Hemingwayesque, men-with-men attitudes. Its point of view about the innate violence of men is essentially that of Peckinpah's The Wild Bunch, but while the idea itself remains valid and even relevant, Mann cancels all that out with a ridiculous ending that suggests some sort of final spiritual, metaphysical mind-meld. To call it mythic absurdity is a kindness.” Entertainment Weekly gave the film a “B-“ rating and Owen Gleiberman wrote, “Mann's most perverse decision was to cast these two legends and then keep them apart from each other. Half-way through, they finally get an extended dialogue in a coffee shop (it's the first time the actors have ever been in a scene together), and you can feel their joy in performing. We're not watching McCauley and Hanna anymore; we're watching De Niro and Pacino trying to out-insinuate each other. For a few moments, Heat truly has some.”

One of the problems critics (and some viewers) had with Heat was Pacino's sudden, loud outbursts of outrageous dialogue. However, the actor justified his character's behavior in an interview: “I think that the character is prone to these kind of explosive irrational outbursts. A lot of those interrogations and that kind of thing, I got from watching detectives working, going into a kind of, flipping into a kind of–flipomatic, as they say–this state of just general chaos in order to get something. The hysteria shakes up the subject and gets to the truth.” Mann further elaborated in an interview where he explained that Pacino's character "will rock that person of his foundation, to the point where the man loses whatever defense mechanisms he may have set up against this detective coming in."

Heat has gone on to inspire numerous other films and filmmakers. Directors for both the Hong Kong crime film Infernal Affairs (2002) and the British gangster film Layer Cake (2004) have cited the look of Heat as an influence on their own work. Most impressively, before going into production on The Dark Knight (2008), director Christopher Nolan screened Heat for all his department heads. He said, “I always felt Heat to be a remarkable demonstration of how you can create a vast universe with one city and balance a very large number of characters and their emotional journeys in an effective manner.” Indeed, the bank heist that begins the film is reminiscent of the one staged in Heat right down to a cameo by William Fichtner as a defiant bank manager in a nice reference to the actor’s role in Mann’s film.

Wednesday, November 17, 2010

DVD of the Week: The Night of the Hunter: Criterion Collection

It is one of the great tragedies of cinema that The Night of the Hunter (1955) was Charles Laughton’s lone film directing credit. An acclaimed character actor by trade, he decided to adapt David Grubb’s 1953 novel of the same name into a haunting southern gothic horror film cum fairy tale. He enlisted film critic/screenwriter James Agee (The African Queen) to write the screenplay and hired cinematographer Stanley Cortez (The Magnificent Ambersons) to bring his considerable expertise to the textured black and white imagery. Sadly, audiences at the time were not ready for this atmospheric fable and it failed to perform at the box office. Laughton died seven years later and never directed another film. However, over the years, The Night of the Hunter was rediscovered by critics and film buffs and its reputation grew as people finally caught up to a film that was ahead of its time. Its legacy is now firmly established and the film is regarded as a classic. It is rather fitting that the Criterion Collection has delivered the definitive edition of this film.

One of The Night of the Hunter’s earliest images is a disturbing one as a group of children playing come across the body of a dead woman. All we see are her legs lying on steps leading down to the cellar of a house. There is something unsettling about how one of her shoes is twisted off an odd angle from her foot. This scene sets the tone for the rest of the film – that of innocence lost. We are soon introduced to Harry Powell (Robert Mitchum), a fire and brimstone preacher who preys on vulnerable widows – killing them and stealing their money, all in the name of God. He talks to God about his disgust for the feminine aspects of women and the next thing we see is him watching a curvy burlesque dancer swaying suggestively in front of him. Powell clearly embodies the dual nature of love and hate – the words of which are tattooed on the fingers of both his hands.

We meet John (Billy Chapin) and Pearl (Sally Jane Bruce) playing in an idyllic rural setting. Their fugitive father, Ben Harper (Peter Graves), arrives with the law hot on his trail. He has stolen $10,000 and hides it amongst his two children. He goes to prison and is put in the same cell as Powell. The crazy preacher finds out about the money but Harper doesn’t tell him where it’s hidden. After his cellmate is executed for his crimes, Powell gets out and makes his way to Harper’s hometown, traveling on an ominous-looking train by night. He ends up marrying Harper’s widow, Willa (Shelley Winters) in an attempt to get closer to the children and find out what happened to the money.

John learns pretty quickly that not many adults can be trusted, especially Powell whom he figures out his true intentions early on. John also looks out for his sister as their mother and her friends are easily captivated by Powell’s charisma. This is beautifully illustrated in a scene where Powell tells the story of love and hate, quoting The Bible with a gusto that is pretty funny and brilliant in the way Robert Mitchum enthusiastically tells it. Normally cast as laconic soldiers (G.I. Joe) or film noir tough guys (Out of the Past) prior to this film, he cranks up the intensity with this role and is not afraid to look silly at one moment and viciously evil in the next. Powell is the film’s metaphorical boogeyman that ends up chasing John and Pearl across the countryside in pursuit of the money like if the Adventures of Huckleberry Finn had been written by William Faulkner.

Laughton gets very impressive performances out of the two children, both of whom more than hold their own with veteran actors like Mitchum, Shelley Winters and Lillian Gish. The latter is excellent as Rachel Cooper, a kind old lady who takes the children in and protects them against Powell. The showdown between her and Mitchum is one of the film’s best scenes.

With The Night of the Hunter, Laughton fuses a theatrical sensibility in the performances with a German expressionistic look that results in a fairy tale unlike any other. There are images that linger afterwards and haunt you for a long time, like the iconic shot of a woman bundled up in a car at the bottom of a lake. The Night of the Hunter explores the destructive nature of greed and the dangers of religious fanaticism while the eternal struggle between love, as represented by Cooper, and hate, as personified by Powell, plays out with the two children’s lives hanging in the balance.

Special Features:

The first disc starts off with an audio commentary moderated by film critic F.X. Feeney and featuring the film’s second-unit director Terry Sanders, film archivist Robert Gitt, and Preston Neal Jones, author of Heaven and Hell to Play With: The Filming of The Night of the Hunter. They point out that Laughton wanted the film to seem like it was being told from the children’s point-of-view, as if they were having a nightmare. The participants analyze the use of humor throughout the film and how it offsets the darkness of the Harry Powell character. They also get into a lively discussion about James Agee’s screenplay and how the original, longer version was very faithful to the source novel. There is some debate about how much of it Laughton rewrote. This is a very informative track, chock full of factoids, analysis and filming anecdotes to satisfy any fan of this film.

“The Making of The Night of the Hunter” is a 38-minute retrospective featurette that takes us through the genesis of the film as producer Paul Gregory talks about how he met Laughton. Interestingly, Laurence Olivier was considered for the role of Powell. Laughton worked closely with Davis Grubb and James Agee to make sure that the film was a faithful adaptation.

“Moving Pictures” is a 15-minute documentary about the film with interviews with key cast and crew members, including Mitchum, Winters and cinematographer Stanley Cortez. While this extra does repeat information from the previous supplement, it is nice to hear these details directly from the people that actually worked on the film.

There is a 1984 interview with Cortez about filming The Night of the Hunter. He speaks admiringly of Laughton and his ability to work with the actors. Cortez says that Laughton knew nothing about the technical aspects of cinematography and trusted him implicitly with the look of the film. Cortez also touches upon the use of light and how he lit certain scenes for a specific effect.

Also included is a theatrical trailer.

“Simon Callow on Charles Laughton” is an interview with the author of Charles Laughton: A Difficult Actor. He talks about the man’s career and how The Night of the Hunter affected his life. Callow points out the irony that Laughton is known more for directing this film than his extensive acting career. He was very active in live theater and this is what led to his involvement in the film. Callow talks about what drew Laughton to Grubb’s novel and covers the production with an obvious emphasis on Laughton.

There is an interest excerpt from the September 25, 1955 episode of The Ed Sullivan Show where Peter Graves and Shelley Winters perform a scene not in the film. Willa visits Harper in prison, which sheds some insight into their relationship.

“Davis Grubb Sketches” is a collection of drawings that he produced for Laughton to help convey how he envisioned his novel. These sketches are juxtaposed with stills from the film to demonstrate how closely Laughton stuck to them while filming.

The second disc contains the crown jewel for fans of the film. “Charles Laughton Directs The Night of the Hunter” is two-and-a-half hours of unused footage and outtakes. There is a conversation between film archivist Robert Gitt and film critic Leonard Maltin that provides some backstory on how this footage was discovered. Gitt was given it in the mid-1970s but it was so disorganized that it took him several years to make sense of it all. Doing it piecemeal when he had the time, he and many volunteers worked away until they had eight hours of footage. He then edited it down to two-and-a-half hours and screened it at UCLA. This footage provides fascinating insight into Laughton’s working methods, especially how he got those great performances out of the two children. For fans of The Night of the Hunter, this is a treasure trove of material.

One of The Night of the Hunter’s earliest images is a disturbing one as a group of children playing come across the body of a dead woman. All we see are her legs lying on steps leading down to the cellar of a house. There is something unsettling about how one of her shoes is twisted off an odd angle from her foot. This scene sets the tone for the rest of the film – that of innocence lost. We are soon introduced to Harry Powell (Robert Mitchum), a fire and brimstone preacher who preys on vulnerable widows – killing them and stealing their money, all in the name of God. He talks to God about his disgust for the feminine aspects of women and the next thing we see is him watching a curvy burlesque dancer swaying suggestively in front of him. Powell clearly embodies the dual nature of love and hate – the words of which are tattooed on the fingers of both his hands.

We meet John (Billy Chapin) and Pearl (Sally Jane Bruce) playing in an idyllic rural setting. Their fugitive father, Ben Harper (Peter Graves), arrives with the law hot on his trail. He has stolen $10,000 and hides it amongst his two children. He goes to prison and is put in the same cell as Powell. The crazy preacher finds out about the money but Harper doesn’t tell him where it’s hidden. After his cellmate is executed for his crimes, Powell gets out and makes his way to Harper’s hometown, traveling on an ominous-looking train by night. He ends up marrying Harper’s widow, Willa (Shelley Winters) in an attempt to get closer to the children and find out what happened to the money.

John learns pretty quickly that not many adults can be trusted, especially Powell whom he figures out his true intentions early on. John also looks out for his sister as their mother and her friends are easily captivated by Powell’s charisma. This is beautifully illustrated in a scene where Powell tells the story of love and hate, quoting The Bible with a gusto that is pretty funny and brilliant in the way Robert Mitchum enthusiastically tells it. Normally cast as laconic soldiers (G.I. Joe) or film noir tough guys (Out of the Past) prior to this film, he cranks up the intensity with this role and is not afraid to look silly at one moment and viciously evil in the next. Powell is the film’s metaphorical boogeyman that ends up chasing John and Pearl across the countryside in pursuit of the money like if the Adventures of Huckleberry Finn had been written by William Faulkner.

Laughton gets very impressive performances out of the two children, both of whom more than hold their own with veteran actors like Mitchum, Shelley Winters and Lillian Gish. The latter is excellent as Rachel Cooper, a kind old lady who takes the children in and protects them against Powell. The showdown between her and Mitchum is one of the film’s best scenes.

With The Night of the Hunter, Laughton fuses a theatrical sensibility in the performances with a German expressionistic look that results in a fairy tale unlike any other. There are images that linger afterwards and haunt you for a long time, like the iconic shot of a woman bundled up in a car at the bottom of a lake. The Night of the Hunter explores the destructive nature of greed and the dangers of religious fanaticism while the eternal struggle between love, as represented by Cooper, and hate, as personified by Powell, plays out with the two children’s lives hanging in the balance.

Special Features:

The first disc starts off with an audio commentary moderated by film critic F.X. Feeney and featuring the film’s second-unit director Terry Sanders, film archivist Robert Gitt, and Preston Neal Jones, author of Heaven and Hell to Play With: The Filming of The Night of the Hunter. They point out that Laughton wanted the film to seem like it was being told from the children’s point-of-view, as if they were having a nightmare. The participants analyze the use of humor throughout the film and how it offsets the darkness of the Harry Powell character. They also get into a lively discussion about James Agee’s screenplay and how the original, longer version was very faithful to the source novel. There is some debate about how much of it Laughton rewrote. This is a very informative track, chock full of factoids, analysis and filming anecdotes to satisfy any fan of this film.

“The Making of The Night of the Hunter” is a 38-minute retrospective featurette that takes us through the genesis of the film as producer Paul Gregory talks about how he met Laughton. Interestingly, Laurence Olivier was considered for the role of Powell. Laughton worked closely with Davis Grubb and James Agee to make sure that the film was a faithful adaptation.

“Moving Pictures” is a 15-minute documentary about the film with interviews with key cast and crew members, including Mitchum, Winters and cinematographer Stanley Cortez. While this extra does repeat information from the previous supplement, it is nice to hear these details directly from the people that actually worked on the film.

There is a 1984 interview with Cortez about filming The Night of the Hunter. He speaks admiringly of Laughton and his ability to work with the actors. Cortez says that Laughton knew nothing about the technical aspects of cinematography and trusted him implicitly with the look of the film. Cortez also touches upon the use of light and how he lit certain scenes for a specific effect.

Also included is a theatrical trailer.

“Simon Callow on Charles Laughton” is an interview with the author of Charles Laughton: A Difficult Actor. He talks about the man’s career and how The Night of the Hunter affected his life. Callow points out the irony that Laughton is known more for directing this film than his extensive acting career. He was very active in live theater and this is what led to his involvement in the film. Callow talks about what drew Laughton to Grubb’s novel and covers the production with an obvious emphasis on Laughton.

There is an interest excerpt from the September 25, 1955 episode of The Ed Sullivan Show where Peter Graves and Shelley Winters perform a scene not in the film. Willa visits Harper in prison, which sheds some insight into their relationship.

“Davis Grubb Sketches” is a collection of drawings that he produced for Laughton to help convey how he envisioned his novel. These sketches are juxtaposed with stills from the film to demonstrate how closely Laughton stuck to them while filming.

The second disc contains the crown jewel for fans of the film. “Charles Laughton Directs The Night of the Hunter” is two-and-a-half hours of unused footage and outtakes. There is a conversation between film archivist Robert Gitt and film critic Leonard Maltin that provides some backstory on how this footage was discovered. Gitt was given it in the mid-1970s but it was so disorganized that it took him several years to make sense of it all. Doing it piecemeal when he had the time, he and many volunteers worked away until they had eight hours of footage. He then edited it down to two-and-a-half hours and screened it at UCLA. This footage provides fascinating insight into Laughton’s working methods, especially how he got those great performances out of the two children. For fans of The Night of the Hunter, this is a treasure trove of material.

Thursday, November 11, 2010

High Fidelity

Have you ever spent hours organizing your record collection in chronological order and by genre? Have you ever had heated debates with your friends about the merits of a band who lost one of its founding members? Or argued about your top five favorite B-sides? If so, chances are you will love High Fidelity (2000), a film for and about characters obsessed with their favorite bands and music. What Free Enterprise (1999) did for film geeks; High Fidelity does for music geeks. Based on the British novel of the same name by Nick Hornby, it is a film made by and for the kind of people who collect vintage vinyl and read musician and band biographies in their spare time yet is still accessible to people who like smart, witty romantic comedies.

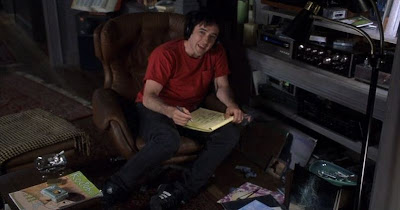

Rob Gordon (John Cusack) is an obsessed music junkie who owns a record store called Championship Vinyl. He has just broken up with Laura (Iben Hjejle), a long-time girlfriend and the latest in a countless string of failed relationships. Rob addresses the audience directly throughout the film (just like Woody Allen did in his 1977 film, Annie Hall) about this latest break-up and how his top five break-ups of all-time inform his most recent one. It’s a great way for Rob to try and come to terms with his shortcomings and the reasons why his past relationships did not work out. He is talking directly to us and in doing so we relate to him and his dilemma a lot easier. And so, he goes on a quest to find out why, as he puts it, “is doomed to be left, doomed to be rejected,” by revisiting his worst break-ups. The purpose of this trip down memory lane is an attempt to understand his most recent falling out with Laura.

Along the way we meet a colorful assortment of characters, from his past girlfriends (that includes the diverse likes of Lili Taylor and Catherine Zeta-Jones) to his co-workers at Championship Vinyl (Jack Black and Todd Louiso). They really flesh out the film to such a degree that I felt like I was seeing aspects of my friends and myself in these characters. Being a self-confessed obsessive type when it comes to film and music, I could easily relate to these people and their problems. And that’s why High Fidelity works so well for me. The extremely funny and wryly observant script by D.V. DeVincentis, Steve Pink, and John Cusack (the same team behind the excellent Grosse Pointe Blank) not only zeroes in on what it is to love something so passionately but why other things (like relationships) often take a backseat as a result. A girlfriend might not always be there for you, but your favorite album or film will. A song will never judge you or walk out on you and there is a kind of comfort in that.

The screenplay also makes some fantastic observations on how men view love and relationships. Throughout the film Cusack’s character delivers several monologues to us about his thoughts on past love affairs, one of my favorite being the top five things he liked about Laura. It’s a touching, hopelessly romantic speech that reminded me a lot of Woody Allen’s list of things to live for in Manhattan (1979). Usually, this technique almost never works (see Kuffs) because it often comes across as being too cute and self-aware for its own good but in High Fidelity it works because Cusack uses it as a kind of confessional as Rob sorts out his feelings for Laura and sorts through past relationships and how they led him to her.

The screenplay works so well because not only is it well written but it is brought to life by a solid ensemble cast. The role of Rob Gordon is clearly tailor-made for John Cusack. Rob contains all the trademarks of the kinds of characters the actor is known for: the cynical, self-deprecating humor, the love of 1980s music, and the inability to commit to the woman of his dreams. Even though High Fidelity is not directed by Cusack, like Grosse Pointe Blank, it is clearly his film, right down to the casting of friends in front of and behind the camera (i.e. actors Tim Robbins, Lili Taylor, his sister Joan, and screenwriters, D.V. DeVincentis and Steve Pink). Along with Say Anything (1989), this is Cusack’s finest performance. I like that he isn’t afraid to play Rob as a hurtful jerk afraid of commitment despite being surrounded by strong women, like his mother who chastises him for breaking up Laura, and his sister Liz (Joan Cusack) who is supportive at first until she finds out why he and Laura really broke up. Rob had an affair with someone else while Laura was pregnant and as a result she got an abortion. This horrible act runs the risk of alienating Rob from the audience but Cusack’s natural charisma keeps us hanging in there to see if Rob can redeem himself.

All of the scenes that take place in the record store are some of the most entertaining and funniest moments in the film, from Rob listing off his top five side one, track ones, to Barry schooling an Echo and the Bunnymen fan on The Jesus and Mary Chain, to Rob fantasizing about beating the shit out of Laura’s new boyfriend Ian (Tim Robbins) when he shows up one day to clear the air. These scenes showcase the excellent comic timing of Cusack and his co-stars, Jack Black and Todd Louiso. The interplay between their characters instantly conveys that they’ve known each other for years by the way they banter and bicker.

Louiso’s Dick is a shy, introverted guy that you can imagine listening to Belle and Sebastian religiously, while Black’s Barry is a rude, annoying blowhard who says everything you wish you could actually say in public. It’s a flashy, scene-stealing role that Black does to perfection, whether it is discussing the merits of Evil Dead II’s soundtrack with Rob or doing a spot-on cover of Marvin Gaye’s “Let’s Get It On” for the launch of Rob’s record label. And yet, Barry isn’t overused and only appears at the right moments and for maximum comic effect. His sparing usage in High Fidelity made me want to see more of him, which is why he works so well. However, Louiso, with his quiet, bashful take on Dick, is the film’s secret weapon. The scene where he tells a customer (Sara Gilbert) about Green Day’s two primary influences which is a nice example of the understatement he brings to the role.

The casting of Danish actress Iben Hjejle is an atypical choice but one that works because she brings an emotional strength and an intelligence to a character that is largely absent from a lot of female romantic leads. She’s not traditionally beautiful, like Catherine Zeta-Jones, who plays one of Rob’s ex-girlfriends, Charlie Nicholson. Sure, Charlie is drop-dead gorgeous but her personality is so off-putting that any kind of deep, meaningful relationship would be impossible. Laura is so much more than that. While Rob refuses to change and to think about the future, Laura is more adaptable, changing jobs to one that she actually enjoys doing even if it means she can’t have her hair dyed some exotic color. Laura is easily Rob’s intellectual equal, if not smarter, and the voice of reason as well as having no problem calling him on his shit.

Nick Hornby’s book was optioned by Disney’s Touchstone division in 1995 where it went into development for the next three years. Disney boss Joe Roth had a conversation with recording executive Kathy Nelson who recommended John Cusack (whom she had worked with on Grosse Pointe Blank) and his screenwriting and producing partners D.V. DeVincentis and Steve Pink adapt the book. They wrote a treatment that was immediately green-lit by Roth. In adapting the book into a screenplay, Cusack found that the greatest challenge was pulling off Rob’s frequent breaking of the fourth wall and talking directly to the audience. They did this to convey Rob’s inner confessional thoughts and were influenced by a similar technique in Alfie (1966). However, Cusack initially rejected this approach because he thought, “there’d just be too much of me.” Once director Stephen Frears came on board, he suggested utilizing this approach and Cusack and his writing partners decided to go for it.

The writers decided to change the book’s setting from London to Chicago because they were more familiar with the city and it also had a “great alternative music scene,” said Pink. Not to mention, both he and Cusack were from the city. I like how they shot so much of the film on location, making the city like another character and even including visual references to local record labels like Touch & Go and Wax Trax! Another challenge they faced was figuring out which songs would go where in High Fidelity because Rob, Dick and Barry “are such musical snobs.” Cusack, DeVincentis and Pink listened to 2,000 songs and picked a staggering 70 cues for the film. DeVincentis was the record-collection obsessive among the writers with 1,000 vinyl records in his collection and thousands of CDs and cassettes. They also thought of the idea to have Rob have a conversation with Bruce Springsteen in his head, never thinking they’d actually get him to be in the film but that putting him in the script would get the studio excited about it. They were inspired by a reference in Hornby’s book where the narrator wishes he could handle his past girlfriends as well as Springsteen does in the song, “Bobby Jean” on Born in the USA. Cusack knew the Boss socially, called the musician and pitched the idea. Springsteen asked for a copy of the script and after reading it, agreed to do the film.

Roger Ebert gave the film four out of four stars and wrote, "Watching High Fidelity, I had the feeling I could walk out of the theater and meet the same people on the street — and want to, which is an even higher compliment.” The Washington Post’s Desson Howe praised Jack Black as "a bundle of verbally ferocious energy. Frankly, whenever he's in the scene, he shoplifts this movie from Cusack.” In his review for The New York Times, Stephen Holden praised Cusack's performance, writing that he was "a master at projecting easygoing camaraderie, he navigates the transitions with such an astonishing naturalness and fluency that you're almost unaware of them." Entertainment Weekly gave the film a "B-" rating and Owen Gleiberman wrote, "In High Fidelity, Rob's music fixation is a signpost of his arrested adolescence; he needs to get past records to find true love. If the movie had had a richer romantic spirit, he might have embraced both in one swooning gesture." Rolling Stone’s Peter Travers wrote, "It hits all the laugh bases, from grins to guffaws. Cusack and his Chicago friends — D.V. DeVincentis and Steve Pink — have rewritten Scott Rosenberg's script to catch Hornby's spirit without losing the sick comic twists they gave 1997's Grosse Pointe Blank." However, the USA Today was not crazy about the film: "Let's be kind and just say High Fidelity ... doesn't quite belong beside Grosse Pointe Blank and The Sure Thing in Cusack's greatest hits collection. It's not that he isn't good. More like miscast." Nick Hornby was impressed by how faithful the film was to his book: “At times it appears to be a film in which John Cusack reads my book.”

High Fidelity is now a historical document thanks to the rise of iTunes and the subsequent demise of brick and mortar record stores. The film is a tribute to these places where one could spend hours sifting through bins of vinyl records and used CDs, looking for that forgotten gem or a rare deal on something you were looking for. I’m not talking about places like Tower Records or Virgin Megastore but those cool, local stores that catered to obsessive collectors. This film is a love letter and a eulogy to these stores. It’s scary to think that it’s only been ten years since High Fidelity came out and indie record stores are almost an extinct breed, except for the ones hanging on in big cities. Even though the world and the characters in High Fidelity are unashamedly of a rarified type: the obsessive music geek or elitist, which some people may have trouble relating to, the film’s conclusion suggests that there is much more to life than one’s all-consuming passion for these things. It also helps to be passionate about someone. And that message is delivered in a refreshingly honest and cliché-free fashion as it provides what is ultimately the humanist core of High Fidelity.

For more on the film, check Chronological Snobbery's excellent retrospective look, here.

Rob Gordon (John Cusack) is an obsessed music junkie who owns a record store called Championship Vinyl. He has just broken up with Laura (Iben Hjejle), a long-time girlfriend and the latest in a countless string of failed relationships. Rob addresses the audience directly throughout the film (just like Woody Allen did in his 1977 film, Annie Hall) about this latest break-up and how his top five break-ups of all-time inform his most recent one. It’s a great way for Rob to try and come to terms with his shortcomings and the reasons why his past relationships did not work out. He is talking directly to us and in doing so we relate to him and his dilemma a lot easier. And so, he goes on a quest to find out why, as he puts it, “is doomed to be left, doomed to be rejected,” by revisiting his worst break-ups. The purpose of this trip down memory lane is an attempt to understand his most recent falling out with Laura.

Along the way we meet a colorful assortment of characters, from his past girlfriends (that includes the diverse likes of Lili Taylor and Catherine Zeta-Jones) to his co-workers at Championship Vinyl (Jack Black and Todd Louiso). They really flesh out the film to such a degree that I felt like I was seeing aspects of my friends and myself in these characters. Being a self-confessed obsessive type when it comes to film and music, I could easily relate to these people and their problems. And that’s why High Fidelity works so well for me. The extremely funny and wryly observant script by D.V. DeVincentis, Steve Pink, and John Cusack (the same team behind the excellent Grosse Pointe Blank) not only zeroes in on what it is to love something so passionately but why other things (like relationships) often take a backseat as a result. A girlfriend might not always be there for you, but your favorite album or film will. A song will never judge you or walk out on you and there is a kind of comfort in that.

The screenplay also makes some fantastic observations on how men view love and relationships. Throughout the film Cusack’s character delivers several monologues to us about his thoughts on past love affairs, one of my favorite being the top five things he liked about Laura. It’s a touching, hopelessly romantic speech that reminded me a lot of Woody Allen’s list of things to live for in Manhattan (1979). Usually, this technique almost never works (see Kuffs) because it often comes across as being too cute and self-aware for its own good but in High Fidelity it works because Cusack uses it as a kind of confessional as Rob sorts out his feelings for Laura and sorts through past relationships and how they led him to her.

The screenplay works so well because not only is it well written but it is brought to life by a solid ensemble cast. The role of Rob Gordon is clearly tailor-made for John Cusack. Rob contains all the trademarks of the kinds of characters the actor is known for: the cynical, self-deprecating humor, the love of 1980s music, and the inability to commit to the woman of his dreams. Even though High Fidelity is not directed by Cusack, like Grosse Pointe Blank, it is clearly his film, right down to the casting of friends in front of and behind the camera (i.e. actors Tim Robbins, Lili Taylor, his sister Joan, and screenwriters, D.V. DeVincentis and Steve Pink). Along with Say Anything (1989), this is Cusack’s finest performance. I like that he isn’t afraid to play Rob as a hurtful jerk afraid of commitment despite being surrounded by strong women, like his mother who chastises him for breaking up Laura, and his sister Liz (Joan Cusack) who is supportive at first until she finds out why he and Laura really broke up. Rob had an affair with someone else while Laura was pregnant and as a result she got an abortion. This horrible act runs the risk of alienating Rob from the audience but Cusack’s natural charisma keeps us hanging in there to see if Rob can redeem himself.

All of the scenes that take place in the record store are some of the most entertaining and funniest moments in the film, from Rob listing off his top five side one, track ones, to Barry schooling an Echo and the Bunnymen fan on The Jesus and Mary Chain, to Rob fantasizing about beating the shit out of Laura’s new boyfriend Ian (Tim Robbins) when he shows up one day to clear the air. These scenes showcase the excellent comic timing of Cusack and his co-stars, Jack Black and Todd Louiso. The interplay between their characters instantly conveys that they’ve known each other for years by the way they banter and bicker.

Louiso’s Dick is a shy, introverted guy that you can imagine listening to Belle and Sebastian religiously, while Black’s Barry is a rude, annoying blowhard who says everything you wish you could actually say in public. It’s a flashy, scene-stealing role that Black does to perfection, whether it is discussing the merits of Evil Dead II’s soundtrack with Rob or doing a spot-on cover of Marvin Gaye’s “Let’s Get It On” for the launch of Rob’s record label. And yet, Barry isn’t overused and only appears at the right moments and for maximum comic effect. His sparing usage in High Fidelity made me want to see more of him, which is why he works so well. However, Louiso, with his quiet, bashful take on Dick, is the film’s secret weapon. The scene where he tells a customer (Sara Gilbert) about Green Day’s two primary influences which is a nice example of the understatement he brings to the role.

The casting of Danish actress Iben Hjejle is an atypical choice but one that works because she brings an emotional strength and an intelligence to a character that is largely absent from a lot of female romantic leads. She’s not traditionally beautiful, like Catherine Zeta-Jones, who plays one of Rob’s ex-girlfriends, Charlie Nicholson. Sure, Charlie is drop-dead gorgeous but her personality is so off-putting that any kind of deep, meaningful relationship would be impossible. Laura is so much more than that. While Rob refuses to change and to think about the future, Laura is more adaptable, changing jobs to one that she actually enjoys doing even if it means she can’t have her hair dyed some exotic color. Laura is easily Rob’s intellectual equal, if not smarter, and the voice of reason as well as having no problem calling him on his shit.

Nick Hornby’s book was optioned by Disney’s Touchstone division in 1995 where it went into development for the next three years. Disney boss Joe Roth had a conversation with recording executive Kathy Nelson who recommended John Cusack (whom she had worked with on Grosse Pointe Blank) and his screenwriting and producing partners D.V. DeVincentis and Steve Pink adapt the book. They wrote a treatment that was immediately green-lit by Roth. In adapting the book into a screenplay, Cusack found that the greatest challenge was pulling off Rob’s frequent breaking of the fourth wall and talking directly to the audience. They did this to convey Rob’s inner confessional thoughts and were influenced by a similar technique in Alfie (1966). However, Cusack initially rejected this approach because he thought, “there’d just be too much of me.” Once director Stephen Frears came on board, he suggested utilizing this approach and Cusack and his writing partners decided to go for it.

The writers decided to change the book’s setting from London to Chicago because they were more familiar with the city and it also had a “great alternative music scene,” said Pink. Not to mention, both he and Cusack were from the city. I like how they shot so much of the film on location, making the city like another character and even including visual references to local record labels like Touch & Go and Wax Trax! Another challenge they faced was figuring out which songs would go where in High Fidelity because Rob, Dick and Barry “are such musical snobs.” Cusack, DeVincentis and Pink listened to 2,000 songs and picked a staggering 70 cues for the film. DeVincentis was the record-collection obsessive among the writers with 1,000 vinyl records in his collection and thousands of CDs and cassettes. They also thought of the idea to have Rob have a conversation with Bruce Springsteen in his head, never thinking they’d actually get him to be in the film but that putting him in the script would get the studio excited about it. They were inspired by a reference in Hornby’s book where the narrator wishes he could handle his past girlfriends as well as Springsteen does in the song, “Bobby Jean” on Born in the USA. Cusack knew the Boss socially, called the musician and pitched the idea. Springsteen asked for a copy of the script and after reading it, agreed to do the film.

Roger Ebert gave the film four out of four stars and wrote, "Watching High Fidelity, I had the feeling I could walk out of the theater and meet the same people on the street — and want to, which is an even higher compliment.” The Washington Post’s Desson Howe praised Jack Black as "a bundle of verbally ferocious energy. Frankly, whenever he's in the scene, he shoplifts this movie from Cusack.” In his review for The New York Times, Stephen Holden praised Cusack's performance, writing that he was "a master at projecting easygoing camaraderie, he navigates the transitions with such an astonishing naturalness and fluency that you're almost unaware of them." Entertainment Weekly gave the film a "B-" rating and Owen Gleiberman wrote, "In High Fidelity, Rob's music fixation is a signpost of his arrested adolescence; he needs to get past records to find true love. If the movie had had a richer romantic spirit, he might have embraced both in one swooning gesture." Rolling Stone’s Peter Travers wrote, "It hits all the laugh bases, from grins to guffaws. Cusack and his Chicago friends — D.V. DeVincentis and Steve Pink — have rewritten Scott Rosenberg's script to catch Hornby's spirit without losing the sick comic twists they gave 1997's Grosse Pointe Blank." However, the USA Today was not crazy about the film: "Let's be kind and just say High Fidelity ... doesn't quite belong beside Grosse Pointe Blank and The Sure Thing in Cusack's greatest hits collection. It's not that he isn't good. More like miscast." Nick Hornby was impressed by how faithful the film was to his book: “At times it appears to be a film in which John Cusack reads my book.”