"I saw the best minds of my

generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked, / dragging

themselves through the negro streets at dawn looking for an angry fix / angelheaded

hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly connection to the starry dynamo in

the machinery of night," - from "Howl" by Allen Ginsberg

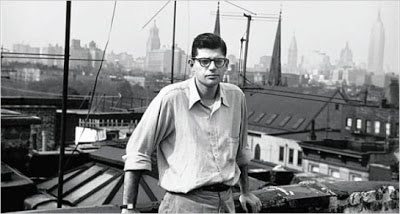

And with those words, poet Allen Ginsberg created a manifesto for a

whole generation – a group of people who felt like they didn't belong anywhere

in 1950s society. Not in the paranoid hype of Senator Joseph McCarthy's

Communist witch hunts, not in President Eisenhower's military war machine, and

not in the sterile sitcom suburbia of Leave

It To Beaver. Ginsberg was speaking for the disenfranchised everywhere with

his poem that celebrated everything that was taboo. The media soon picked up on

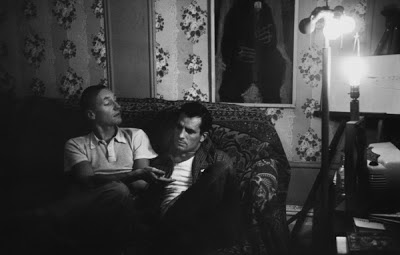

this small movement, and built up its most charismatic members – Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, and William S. Burroughs – to mythic proportions. The Beat Generation,

as it came to be known, began to mutate into something different from its

original intentions. Antiquated terms like "beatnik" and

"hipster" became the watchwords of this new entity. It even acquired

its own dress code: berets, turtlenecks, and goatees, all to the beat of the

bongos. In short the Beat Generation became a parody of itself. But it didn't

start out that way.

In 1943, a young Allen Ginsberg arrived at Columbia University in New

York City with the intention of becoming a labor lawyer. Being the son of a

poet, Ginsberg had some pretensions to the written word and with fellow

undergraduate Lucien Carr they became interested in finding a "New

Vision" in literature. This pursuit led them to form a friendship with two

aspiring writers, Jack Kerouac and William S. Burroughs in 1944. Kerouac was at

Columbia on a football scholarship, but an injury had cut his career short and

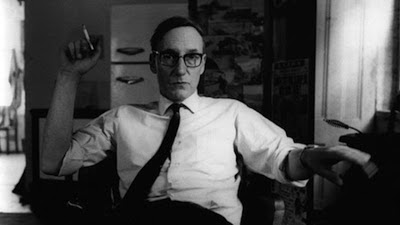

as a result he began to study literature. Burroughs met the other three men

through an acquaintance of Kerouac's and impressed them with his vast knowledge

of literature and the refined way in which he carried himself. Being older than

the others, Burroughs became like a teacher to the young men, introducing them

to all kinds of European authors and initiating them into drug culture. He

subsequently presented the group to his drug contact, Herbert Huncke, a Times

Square hustler who embodied what would later become the rather nebulous term,

"beat."

The arrival of 1946 brought an important element to this ever-increasing

group of writers. Neal Cassady, a friend of Ginsberg's from Denver, arrived in

New York City on a Greyhound bus and became Ginsberg's lover and good friends

with Kerouac. Cassady, with his charismatic manic energy, was an important

catalyst to the group – particularly to Kerouac who transformed Cassady into

the mythical central character of two of his novels, On the Road and Visions of Cody. Cassady also symbolized everything that was "beat" but on

the opposite end of the spectrum to Huncke: he was wild, unpredictable, and,

more importantly in Kerouac's eyes, the essence of spontaneity. Along with

be-bop jazz, Cassady's frenetic lifestyle provided the inspiration for

Kerouac's own literary style, which he later called, "Spontaneous Bop

Prosody." In essence, it was Kerouac's attempt to emulate jazz in his

prose. As he once explained, "by not revising what you've already written

you simply give the reader the actual workings of your mind during the writing

itself." The musical cadences in Kerouac's work become readily apparent

when you hear the man himself read his own prose and this gives a whole new

perspective to the printed word.

"...because the only people

for me are the mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be

saved, desirous of everything at the same time, the ones who never say a

commonplace thing, but burn, burn, burn like fabulous yellow roman

candles..." - from On the Road by Jack Kerouac

The group now had all the elements that they needed for their "New

Vision" except a name for their group, which did not present itself until

1948 when Kerouac met another aspiring writer in New York named John Clellon Holmes. As Kerouac remembers they were "sitting around trying to think up

the meaning of the Lost Generation and the subsequent Existentialism and I said

'You know this is really a beat generation.' And he leapt up and said

"That's it, that's right!'" The "beat" for Kerouac and the

others took on several meanings. It could be seen as being "beat" and

"beaten down," as in being tired and worn out, or the

"beat" could be interpreted as "beatitude," or a sincere

belief in spirituality and God, or the third significant distinction of the

word was applied to the rhythmic beat of jazz and the fast tempo of this musical

form. Despite the many meanings of the word "beat," the core of this

crew, according to Kerouac, was "a swinging group of new American men

intent on joy," and not a group of hoodlums and criminals as the media

later tried to label them.

However, Kerouac and the others were hardly angels either. More than

anything they were a product of post-World War II malaise and out of this

developed Ginsberg's fear of the atomic age: a fear of the bomb, a fear of

contamination, and of radiation sickness or what he saw as a "disease of

the age." To escape this fear, the group experimented with all kinds of

drugs: marijuana, morphine, heroin, and Benzedrine which fueled their writing

and aided in what Ginsberg termed, "some kind of opening of mind." It

also pushed them outside of mainstream society so that they became a

"community of outlaws," as Burroughs biographer, Ted Morgan later

observed. Burroughs was known to forge stolen prescriptions for drugs and often

robbed drunks on the subway for money. Kerouac even went to jail as a material

witness for helping Lucien Carr destroy evidence after the latter had fatally

stabbed David Kammerer, another member of their group while at Columbia. This

incident also resulted in Ginsberg being sent to the Columbia Psychiatric Institute

for a short duration. They were no strangers to the fringes of society, for

they constantly lived on its edges.

"And always cops: smooth

college-trained state cops, practiced, apologetic patter, electronic eyes weigh

your car and luggage, clothes and face; snarling big city dicks, soft-spoken

country sheriffs with something black and menacing in old eyes color of a faded

grey flannel shirt...." - from Naked Lunch by William S. Burroughs

Despite this dangerous side of the Beats, they were really romantics who

celebrated the little things in life that most people took for granted or

failed to notice. For Kerouac and the others, they were on a spiritual journey

that involved "walking talking poetry in the streets, walking talking God

in the streets," as Kerouac so eloquently described it in an essay for Playboy magazine. Critics and the media

tried to paint them into a corner as troublemakers who were against the world,

but they refused to be pigeon-holed by this view. In most of his public

appearances, most notably on The Steve

Allen Show, Kerouac came across as gentle, sincerely religious soul who

celebrated life, not condemning it. "This is Beat," he once said,

"Live your lives out? Naw, love your lives out."

By the early to mid-fifties, the East Coast Beats began to disperse and

Ginsberg headed out West where the scene developed in San Francisco with poets

like Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Gary Snyder, and Michael McClure amongst others.

Kerouac and the others were going in their own directions but the friendships

between them endured over the years. This small, initially tight-knit group had

inadvertently created the blueprint for a bohemian community. They were what

historian Alfred Kazin called a "family of friends." They fed off

each other, inspired each other, and generally supported one another's interest

in writing. The result was astounding. Some of the most exciting literature to

appear in the 20th century came out of this community: Kerouac's ode to travel,

On the Road, Ginsberg's epic poem,

"Howl," and Burroughs' hallucinogenic satire, Naked Lunch. They inspired a subsequent generation and their works

continue to inspire and fascinate today. Despite what critics of their day said,

they were no fad, no flavor-of-the-month, but a strong new voice that showed a

different perspective on life: living for the moment. Their philosophy didn't

fit the modern, fast paced, 9-to-5 rat race, but rather celebrated shifting

gears and enjoying life for the short time that we experience it.

"...and nobody, nobody knows

what's going to happen to anybody besides the forlorn rags of growing old, I

think of Dean Moriarty, I even think of Old Dean Moriarty the father we never

found, I think of Dean Moriarty." - from On the Road by Jack Kerouac

Wonderful overview! They were quite a group alright, although I have to say Jack was my favorite of the lot. I just love his sense of lyricism.

ReplyDeleteBrent Allard:

ReplyDeleteThanks! Yeah, Kerouac is my fave as well. I got into him in a big big way during my last year in high school and quickly read everything I could get my hands on.