When 28 Days Later came out in 2002, it was perceived as a welcome breath of fresh air in the horror and science fiction genres which had become stagnant and predictable. It proved that in the best tradition of Night of the Living Dead (1968) and Halloween (1978), the most effective horror films are made independently, and that they can scare us while also making us think. 28 Days Later is generally considered to be a post-apocalyptic science fiction film — after all, the premise involves Great Britain ravaged by a highly contagious virus and follows the adventures of four survivors. However, director Danny Boyle shoots his film in a way that shifts from ominous feelings of dread to outright sweaty-palmed terror reminiscent of George Romero’s zombie films albeit on speed.

28 Days Later struck a nerve not just among horror fans but moviegoers in general and was a surprise success. The inevitable sequel followed, but instead of going for an easy, quickie film that coasts on the reputation of its predecessor, 28 Weeks Later (2007) uses the effects of the virus outbreak and the government’s reaction to it as a commentary on real-life bureaucratic reactions to Hurricane Katrina and the war in Iraq. Even more impressively, 28 Weeks Later is a rare sequel that is as good if not better than its predecessor.

In 28 Days Later, Jim (Cillian Murphy) wakes up in a hospital 28 days after three animal activists broke into the Cambridge Primate Research Facility to free chimpanzees being experimented on but unwittingly released a virus known as Rage into British society. Unaware of what has transpired, Jim wanders the gloomily empty streets of downtown London trying to figure out what the hell is going on. Buses and trucks are overturned and abandoned while the normally clean streets are littered with trash and, in one instance, some money (although it’s pretty much useless now). Jim picks up a newspaper and quickly gets an inkling of what went down — the country has been evacuated as the Rage virus devastated the population.

Jim walks up the steps in a church and behind him someone has painted on the wall in large letters, “The end is extremely fucking nigh,” which sets just the right creepy tone. He walks into the chapel and it is packed with dead bodies like some kind of perverse variation on the Jonestown Massacre. He also encounters his first infected person as a priest rushes crazily at him and Jim barely escapes. In doing so, he encounters two other survivors who rescue him by torching a few infected people with Molotov cocktails but they keep on coming despite being transformed into human torches. Mark (Noah Huntley) and Selena (Naomie Harris) fill Jim in on what has happened while he was in the hospital and how far the infection has spread. And so begins Jim’s quest to find other survivors and a safe haven to hold up until this epidemic plays out.

Boyle times his jolts well, like when Jim reflects on his dead parents in their home when suddenly two of their neighbors, out of their heads with the virus, come bursting in. Mark and Selena intervene but he gets some of the infected blood into a wound and that’s all it takes to become infected. She unhesitatingly hacks him to death with a machete in a truly horrifying scene. It’s not just the sudden nature of the attack but the brutal way in which Selena deals with Mark. She is a refreshingly practical character who lays it all out for Jim: “Plans are pointless. Staying alive’s as good as it gets.” When you’ve had to kill loved ones or watched them die, there isn’t much room for hope or romanticism and a survival instinct takes over.

Boyle wisely cast relative unknowns (at the time) Cillian Murphy (Batman Begins) and Naomie Harris (Miami Vice) who had no movie star baggage and weren’t linked to iconic roles yet. This gives 28 Days Later an unpredictable edge as we don’t know who will live or die. They are supported by veteran character actors Christopher Eccleston (The Others) and Brendan Gleeson (In Bruges). Eccleston, who appeared in Boyle’s first film Shallow Grave (1994), brings an edgy intensity to his role of a twisted military commander, while Gleeson plays a good-natured survivor with a daughter (Megan Burns) that Jim and Selena meet in London. Eccleston and Gleeson bring the necessary gravitas to their respective roles and this helps anchor the film.

Many reviewers mistakenly referred to the infected as zombies. They aren’t the lumbering undead; they’re infected — fast and very lethal. 28 Days Later was compared to George A. Romero’s Dead films, which, to a degree is apt because they both deal with post-apocalyptic societies struggling to survive against overwhelming odds. There are the obvious nods to Romero’s Dawn of the Dead (1978) with the carefree shopping spree in a deserted supermarket and the tense attempt to get gas at a seemingly deserted station. However, the Romero film 28 Days Later most closely echoes is The Crazies (1973) about a small community whose inhabitants are driven insane by a government created biological weapon. Boyle’s film is obviously on a much larger scale but some of the same ideas are explored, such as the disintegration of society as the result of government sanctioned experiments. As with Romero’s films, the military are not to be trusted as evident with Major Henry West (Christopher Eccleston) and his warped cure for the infected and the way he maintains order among the uninfected. He’s drunk on power, much like Captain Rhodes (Joe Pilato), the military leader in Day of the Dead (1985).

28 Days Later is a powerful statement about how easily societal order can break down bringing out the best and worst in us. It presents characters we grow to care about and become emotionally invested in. The film also delivers the requisite thrills and genuine scares that are strategically positioned for maximum effect. 28 Weeks Later starts off with a bang as a small cottage of survivors living outside of London is attacked by a horde of the infected with only one person managing to escape. Donald Harris (Robert Carlyle) abandons his wife (Catherine McCormack) to save his own skin — a split-second decision he deeply regrets and which will have serious repercussions later on. Shaky, hand-held camerawork captures his desperate escape from the infected with incredible, frenetic intensity that quickly establishes the film’s grim tone. Don makes it to safety and is reunited with his two children, Andy (Mackintosh Muggleton) and Tammy (Imogen Poots), in London.

It is 28 weeks after the initial outbreak and all the infected have starved to death. The United States military have occupied London and are allowing refugees back in. Sound familiar? Shades of post-Katrina New Orleans anyone? Andy and Tammy defy the safety zone laws and return to their home to pick up some stuff. In the process, they are reunited with their mother who has been infected but for some unknown reason has not gone crazy like the others. In what will prove to be a fatal error in judgment, the military decide to study Don’s wife instead of destroying her outright. Once all hell breaks loose, Andy, Tammy, Scarlett (Rose Byrne), a doctor they meet, and Sergeant Doyle (Jeremy Renner), a soldier who helps them escape during the chaos of the new outbreak, try to find a way out of London.

The film is rife with references to Katrina. Once the virus breaks out, a group of refugees are herded into an underground parking garage for their “safety” only for order to break down a la the Superdome debacle. Later, as the refugees flee through the streets with the infected in pursuit, the military give up trying to target the infected and begin shooting everyone that eerily echoes the Northern Ireland massacre in 1972.

28 Weeks Later is one of those all-bets-are-off horror films where you really don’t know who is going to live and who is going to die. There are safety zones, such as big name movie stars, that often indicate who will survive, but not in this film which only enhances the unbelievable tension that the filmmakers create. It is very rare that a sequel is as good as or better than the one that came before it — The Godfather Part II (1974) and The Bourne Supremacy (2004) come immediately to mind. The filmmakers behind 28 Weeks Later are not merely content to rehash the first film. They build on it and go off in new and exciting directions, expanding the world that was created in 28 Days Later.

"...the main purpose of criticism...is not to make its readers agree, nice as that is, but to make them, by whatever orthodox or unorthodox method, think." - John Simon

"The great enemy of clear language is insincerity." - George Orwell

Friday, March 30, 2012

Friday, March 23, 2012

Extreme Prejudice

Film director Walter Hill has had, at times, a frustratingly and wildly uneven career that features stone cold classics (The Warriors) alongside baffling misfires (Crossroads). His main stock and trade is old school tough guy action films and they don’t come anymore badass than the criminally underrated Extreme Prejudice (1987). Based on a story co-written by John Milius (Apocalypse Now) and starring Nick Nolte and Powers Boothe, it was Hill’s two-fisted homage to the films of Sam Peckinpah who he had worked for early on his career as the screenwriter for The Getaway (1972). Like many of Hill’s own action films, Extreme Prejudice is a modern western featuring two uncompromising men at odds with one another.

Six mysterious men show up in El Paso, Texas. Officially listed as dead by the United States government, they are part of an elite top-secret military unit led by the no-nonsense Paul Hackett (Michael Ironside), a D.E.A. agent. We soon meet Texas Ranger Jack Benteen (Nick Nolte), a lawman with the cojones to go into a crowded Mexican bar with a loaded rifle looking for a suspect only to coolly gun him down when the guy pulls a pistol. He teams up with local county sheriff Hank Pearson (Rip Torn), the man who taught him how to be a lawman. It turns out that the suspect was a “poor dirt farmer” running dope for Cash Bailey (Powers Boothe) in order to make ends meet. Cash is the local drug kingpin and a man so tough he lets a scorpion crawl along his hand before crushing it. He and Jack were best friends in high school but now they are on opposite sides of the law. Unbeknownst to Jack, Hackett and his men are intent on busting Cash as well.

Nick Nolte plays one of Hill’s trademark laconic men of action and of few words, like the enigmatic getaway driver in The Driver (1978), Swan in The Warriors (1979) and Tom Cody in Streets of Fire (1984). Jack and Cash are throwbacks to a bygone era. 100 years ago they’d have been gunslingers in the Wild West. Nolte has got the steely determination thing down cold and an innate understanding of Hill’s worldview, embodying it with ease. Like many of the director’s protagonists, Jack doesn’t like to talk about his feelings, not even to his long-suffering girlfriend (Maria Conchita Alonso). He’d rather do something than talk about it. It’s great to see him reunited with Hill after their initial collaboration on 48 Hrs. (1982). In an ideal world, they would be making all kinds of films together with Nolte the De Niro to Hill’s Scorsese, both bringing out the best in each other.

For the role of Jack, Hill wanted someone who was “representative of the tradition of the American West – taciturn, stoical, enduring,” and had Nolte watch a lot of films starring Gary Cooper, Randolph Scott and John Wayne. Nolte wanted to recapture “the demeanor of how those ‘40s characters carried themselves – how they dressed and carried their guns.” In order to play a credible Texas Ranger, the actor asked writer friend Peter Gent (North Dallas Forty) to recommend someone to act as a model for his character. Gent suggested real-life Ranger Joaquin Jackson. He and Nolte went over the screenplay and incorporated more of the type of language Rangers use and their relationship with other law enforcement agencies.

In a precursor to his grinning baddie in Tombstone (1993), Powers Boothe plays a genial antagonist in Extreme Prejudice while also sporting a dapper white suit. Cash sees the drug trade as simply giving the people what they want. Early on, Boothe has a nice scene with Nolte where their two characters meet and Jack warns Cash that if he crosses the border into the U.S. he will bust him and his operation. Unfazed and as cool as they come, Cash says to his old friend, “I got a feeling the next time we run into each other we’re gonna have a killing. Just a feeling.” Think of this scene as the pulpy precursor to the legendary diner scene in Heat (1995) between Robert De Niro and Al Pacino only with two legendary character actors instead. The message in both scenes is the same: the next time Cash and Jack meet, one of them is not going to survive the encounter. For any fan of these two actors, this scene (and their final one at the end of the film) is a lot of fun to watch as these forces of nature square off against each other with Cash being gregarious yet still threatening and Jack all stoic determination. With his portrayal, Boothe has said that he wanted Cash to be “multi-faceted, a fully-rounded human being.” I don’t know if he achieves that exactly, but Cash is certainly more than a mere stock villainous character.

The cast of Extreme Prejudice is populated with an embarrassment of character acting riches. William Forsythe (The Devil’s Rejects) plays a grinning good ol’ boy troublemaker; Michael Ironside (Scanners) is the all-business leader of a group of soldiers; Clancy Brown (Highlander) is one of his reliable henchmen; and Rip Torn plays Jack’s mentor who recognizes what Cash represents: “How it comes around. Right way’s the hardest. Wrong way’s the easiest. Rule of nature, like water seeks the path of least resistance so you get crooked rivers and crooked men.” Well said, sir!

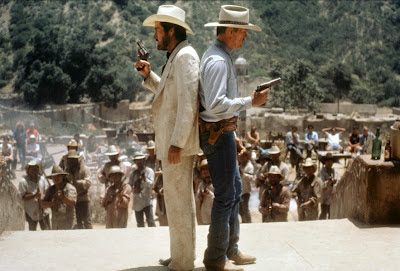

Hill not only indulges in his Peckinpah admiration with some of the film’s themes but more explicitly in how he stages and edits the exciting action sequences complete with slow motion carnage that culminates in the climactic bloodbath between Jack, Hackett and his men and Cash and his private army that evokes the penultimate showdown in The Wild Bunch (1969). This is also evident Hill’s storytelling method as Extreme Prejudice is trimmed of any unnecessary narrative fat. Every scene services the story with refreshing efficiency by someone who knows how to tell a story and tell it well.

At the time, Extreme Prejudice was viewed as Hill’s take on the drug wars and the U.S. government’s handling of it with Jack as his mouthpiece when he tells Hackett at one point, “Bunch of bureaucratic fat asses fluffing their duff. They been sitting on my request for drug information for over a year but it’s classified. They’re afraid somebody or some country’s gonna get their feelings hurt.” Hill clearly sees the government as an impediment rather than a resource to men like Jack who are fighting the war in the trenches, dealing with it on a daily basis. The director said in an interview that he saw the film as a critique of “machismo politics” and of “American military involvement beyond our borders, beyond constitutional means.”

Extreme Prejudice is highly critical of the drug wars but refuses to be preachy about it as is the tendency of films like Traffic (2000). Hill is more interested in depicting the struggles of foot soldiers like Jack and how it affects him personally. It also suggests that the government regards people like Hackett and his men as “just numbers on a bureaucratic desk,” as one character puts it. Jack and Cash are above all that because they don’t care about the system. They work within it when they have to but have their own personal code of honor, which they follow. This highly critical viewpoint may explain why it took 10 years for the film to get made, going through several studios and directors because of its “political ramifications” as Boothe said in an interview.

Extreme Prejudice received a perfunctory theatrical release and was not a commercial success. It received mostly positive reviews from critics. Roger Ebert gave the film three out of four stars and wrote, “What makes the film good are Hill’s style and the acting.” In her review for The New York Times, Janet Maslin wrote, “If Mr. Hill, whose best films have a genuinely hard-boiled glamour, never intends this as parody, neither is he ever more than a hair away.” The Chicago Tribune’s Dave Kehr wrote, “If characters are caught in a shrinking world that leaves no room for notions as grand as ‘good’ and ‘evil,’ but only a sordid, creeping malignancy that levels everything in its path.” In his review for the Los Angeles Times, Kevin Thomas wrote, “Sensational rather than serious, it is an exploitation picture but one with class: it has style, a point to make that happens to be highly topical and, thankfully, a dry, saving sense of humor.” However, the Washington Post’s Richard Harrington felt that “there are simply too many problems, starting with Hill’s clumsy exposition and clumsier development.” Newsweek magazine’s David Ansen was also critical of “Hill’s calcified, comic-book notion of movie machismo.” Extreme Prejudice has largely been forgotten, even by fans of Hill’s films, but deserves to be rediscovered and recognized as one of his very best efforts.

NOTE: This post was inspired by Sean Gill's own highly entertaining review over at his blog.

NOTE: This post was inspired by Sean Gill's own highly entertaining review over at his blog.

SOURCES

Lovell, Glenn. “Nick Nolte

Far From Down, Out.” Orlando Sentinel. April 29, 1987.

“Names in the News.” Associated

Press. April 25, 1987.

Scott, Vernon. “The Rev. Jim

Jones Haunts Actor.” United Press International. May 27, 1987.

Friday, March 16, 2012

Re-Animator

Armed with razor-sharp wit and a plethora of plasma, Re-Animator splashed its way onto movie screens in 1985 and more than 25 years later still continues to haunt the living. By using a then-obscure H.P. Lovecraft story as a springboard, director Stuart Gordon dove head first into the realm of postmortem peculiarities, and ironically offered a pleasing marriage of humor and horror. So, what exactly is being reanimated, you ask? Well that depends on what’s available: cats, colleagues, girlfriends. They have to be dead, of course, and the fresher the better. Okay, I know, once you’re dead, you’re dead: enter the Grim Reaper and good-bye soul. But what if death could be reversed? No, it’s impossible; death is the only inevitability that we know is certain...or is it?

The story centers around Herbert West (Jeffrey Combs), an enigmatic medical student recently arrived at Miskatonic University, and whose liquid lunch for the dead promises a miraculous rebirth just in time for dinner. With the help of his roommate Dan Cain (Bruce Abbott), the two crazed, but persistent demigods syringe their languid recipients until some sign of life occurs. Unfortunately, the dead don’t always return smiling, and by some hideous defiance of natural law, they have come back with a vicious vengeance for anything and anyone in their way. This postmodern clash of the titans between the alive and the half-alive achieves epic harmony in no other battleground more appropriate than the hospital morgue, which offers an outstanding surplus of bodies and blood that would make any jaded gorehound scream for more and raised the bar on the amount of carnage depicted on-screen (until Peter Jackson’s Braindead came along, that is).

The film’s tantalizing prologue creates just the right amount of dread and mystery as a young man crouches over the body of an older man writhing in pain. The authorities come busting in only to witness the old man’s eyeballs pop out like zits. A nurse accuses the younger man of killing the other to which he denies and says, turning dramatically to face the camera, “I gave him life.” Welcome to Re-Animator and the opening credits play over Richard Band’s loving homage to Bernard Hermann’s music for the opening credits of Psycho (1960).

We meet Dan trying desperately to save a patient that’s flatlined. Even after others have given up he still tries. He takes the body to the morgue where we meet Dr. Carl Hill (David Gale) for the first time as he uses a laser on a corpse’s skull. Dean Alan Halsey (Robert Sampson) introduces Dan to West who proceeds to arrogantly and openly challenge Hill’s work on the limit of life of the brain stem after death. It’s fun to see the prickly West square off against the haughty Hill as the former slams the latter’s work as being derivative to the point of plagiarism. This is only the beginning of an ongoing feud that develops between the two men. There’s clearly not enough room on campus for both of their inflated egos. West soon moves in with Dan, who is looking for a roommate to share the rent, much to the chagrin of the latter’s girlfriend, Megan (Barbara Crampton), the Dean’s daughter who is unaware that his child is having sex with one of his students. West begins conducting experiments in the basement with his own reagent, reanimating dead animals before moving on to human cadavers at the university.

All of these ingredients are fine and dandy, but Re-Animator did not rise to cult status by special effects alone. The curse of a low budget actually fashions an intriguing cast of nobodies, and the stone-faced seriousness with which these actors engage the witty, death-induced dialogue adds a parodic twist to a sometimes melodramatic genre. Chief among them is Jeffrey Combs who plays West with just the right amount of weasely bravado, which he conveys so well with the clipped speech patterns of someone who doesn’t suffer fools gladly and says exactly what he means. I like the way he gives his dialogue a slightly melodramatic spin that never gets too cartoonish but chews just enough scenery to make his take on West very memorable. His character is obsessed with conquering brain death to the point of lunacy and it is fun to watch as his experiments become more ambitious and extreme.

I love the petulant way Combs’ West acts at Hill’s lecture, breaking two pencils at strategic points during the class until the exasperated professor tells him, “I suggest you get yourself a pen!” And then West lets him have it” You know, you should have stolen more of Gruber’s ideas then at least you’d have ideas.” David Gale nails the pompous Dr. Hill’s self-importance and feelings of superiority over everybody around him. He’s the bad guy you love to hate and his scenes with Combs are a lot of fun as we watch these two egotists butt heads.

Bruce Abbott has the unenviable task of playing the upstanding good guy Dan but thanks to the sharply written screenplay by Gordon, William J. Norris, and Dennis Paoli, he is given a substantial character to inhabit and we can easily relate to him. Dan becomes more conflicted as the film progresses and he finds himself caught up in West’s schemes to conquer death. Abbott may not get the most memorable dialogue to spout but he grounds the film with his everyman character caught up in extraordinary circumstances. He also plays well off Combs’ mad scientist, acting as the voice of reason in an increasingly strange world. Abbott is particularly strong in the sequence where he and West reanimate a cadaver and things go badly. While West continues to rant and rave, already looking ahead to the next experiment, Dan goes into shock after having witnessed a dead body coming back to life and go apeshit on Dean Halsey, killing him. Dan reacts like any rational human being would in that situation and Abbott’s performance grounds the film at just the right moments so that we accept the more outlandish ones.

Genre darling Barbara Crampton (From Beyond) manages to make what is basically a damsel in distress role memorable with her spunky charm and beautiful looks, not to mention her courage, which is put to the test in the film’s most infamous scene where Dr. Hill’s reanimated severed head attempts to perform a sexual act on her while she’s tied up that has to be seen to be believed. Beyond that, Crampton does a nice job of conveying the emotional breakdown of Meg after Dan tells her about her father’s death and then has to accept his reanimated resurrection.

As Re-Animator progresses, Gordon continues to up the ante in terms of gory set pieces. In the first one, West is armed with a syringe of his reagent, from there he moves on to a dead cat and then deals with an ornery human cadaver with a bone saw, culminating in the final showdown between Dan and West and Dr. Hill and his small army of reanimated corpses, which gives the film’s dazzling makeup effects quite a workout. For a low-budget film, they are surprisingly excellent and it helps that the actors do a lot to really sell it.

The idea to make Re-Animator came from a discussion Stuart Gordon had with friends one night about vampire films. He felt that there were too many Dracula movies and expressed a desire to see a Frankenstein one. Someone asked if he had read Herbert West – Re-Animator by H.P. Lovecraft. Gordon had read most of Lovecraft’s works but that book had been out of print and so he read a copy of it at the Chicago Public Library.

Originally, Gordon was going to adapt Re-Animator for his theater company the Organic Theater and then, at some point, decided to make it as a horror film using the theater as a soundstage. However, the powers that be didn’t like the idea of him making a horror film and felt that he should be making an art film instead. Then, he and writers Dennis Paoli and William Norris decided to do it as a half-hour television pilot. The story was originally set around the turn of the century and they realized that it would be too expensive to be recreated and updated it to the present day in Chicago, using actors from the Organic Theater Company of which Gordon was a member. They were told that the half-hour format was not salable and so they made it an hour, writing 13 episodes. Gordon was then told that the only market for the horror genre was in feature films. He was soon introduced to producer Brian Yuzna by mutual friend Bob Greenberg, a special effects artist who had worked on John Carpenter’s Dark Star (1974).

Yuzna saw Gordon’s current play entitled, ER, about an emergency room and was impressed with the screenplay for the pilot and the 13 episodes. Greenberg and Yuzna convinced Gordon to shoot Re-Animator in Hollywood because of all the special effects involved. Once there, Yuzna made a distribution deal with Charles Band’s Empire Pictures in return for post-production services. The budget was set for just under a million dollars with Yuzna describing it as having the “sort of shock sensibility of an Evil Dead with the production values of, hopefully, The Howling.” For research, Gordon and Yuzna interviewed several pathologists and toured a morgue in Los Angeles. Once the actors were cast, Gordon took them on a tour of the Cook County morgue in Chicago to show them how the bodies were treated and how the people who worked acted. A lot of the film’s gallows humor came from the pathologists he met.

John Naulin worked on Re-Animator’s gruesome makeup effects and drew inspiration from “disgusting shots brought out from the Cook County morgue of all kinds of different lividities and different corpses.” He and Gordon also used a book of forensic pathology in order to present how a corpse looks once the blood settles in the body, creating a variety of odd skin tones. Naulin said that it was the bloodiest film he had ever worked on. In the past, he never used more than two gallons of blood on a film. On Re-Animator, he used 24 gallons of blood. The biggest makeup challenge in the film was the headless Dr. Hill zombie. Tony Doublin designed the mechanical effects and was faced with the problem of proportion once the 9-10 inches of the head were removed. Each scene had to use a different technique. For example, one involved building an upper torso that actor David Gale could bend over and stick his head through so that it appeared to be the one that the walking corpse was carrying around.

Re-Animator received positive reviews from critics back in the day. Roger Ebert gave the film three out of four stars and found it to be, “a frankly gory horror movie that finds a rhythm and a style that make it work in a cockeyed, offbeat sort of way. It's charged up by the tension between the director's desire to make a good movie, and his realization that few movies about mad scientists and dead body parts are ever likely to be very good.” The New York Times’ Janet Maslin felt that it, “has a fast pace and a good deal of grisly vitality. It even has a sense of humor, albeit one that would be lost on 99.9 percent of any ordinary moviegoing crowd.” In his review for the Los Angeles Times, Kevin Thomas praised Combs’ performance: “The big noise is Combs, a small, compact man of terrific intensity and concentration.” Pauline Kael herself raved about it: “It’s like pop Bunuel, the jokes hit you in a subterranean comic zone that the surrealists’ pranks sometimes reached, but without the surrealists’ self-consciousness.”

When Re-Animator came out there hadn’t been a good mad scientist movie in some time. The horror genre during the early to mid ‘80s had been dominated by the slasher franchises of Friday the 13th, Halloween and A Nightmare on Elm Street so Gordon’s film felt like a breath of fresh air. It went on to develop enough of a cult following to spawn two sequels – Bride of Re-Animator (1990) and Beyond Re-Animator (2003) – and a musical proving that Lovecraft’s original story continues to fascinate people. It may also be the age-old theme of science messing with things, like death, with disastrous results. The film features a battle between two brilliant men recklessly playing God without thinking about the consequences.

Doughton, K.J. “Stuart Gordon: Body of Work.” Film Threat. July 17, 2002.

Williams, Ross. “Stuart Gordon: King of the Gorehounds.” Film Threat. July 9, 2003.

The story centers around Herbert West (Jeffrey Combs), an enigmatic medical student recently arrived at Miskatonic University, and whose liquid lunch for the dead promises a miraculous rebirth just in time for dinner. With the help of his roommate Dan Cain (Bruce Abbott), the two crazed, but persistent demigods syringe their languid recipients until some sign of life occurs. Unfortunately, the dead don’t always return smiling, and by some hideous defiance of natural law, they have come back with a vicious vengeance for anything and anyone in their way. This postmodern clash of the titans between the alive and the half-alive achieves epic harmony in no other battleground more appropriate than the hospital morgue, which offers an outstanding surplus of bodies and blood that would make any jaded gorehound scream for more and raised the bar on the amount of carnage depicted on-screen (until Peter Jackson’s Braindead came along, that is).

The film’s tantalizing prologue creates just the right amount of dread and mystery as a young man crouches over the body of an older man writhing in pain. The authorities come busting in only to witness the old man’s eyeballs pop out like zits. A nurse accuses the younger man of killing the other to which he denies and says, turning dramatically to face the camera, “I gave him life.” Welcome to Re-Animator and the opening credits play over Richard Band’s loving homage to Bernard Hermann’s music for the opening credits of Psycho (1960).

We meet Dan trying desperately to save a patient that’s flatlined. Even after others have given up he still tries. He takes the body to the morgue where we meet Dr. Carl Hill (David Gale) for the first time as he uses a laser on a corpse’s skull. Dean Alan Halsey (Robert Sampson) introduces Dan to West who proceeds to arrogantly and openly challenge Hill’s work on the limit of life of the brain stem after death. It’s fun to see the prickly West square off against the haughty Hill as the former slams the latter’s work as being derivative to the point of plagiarism. This is only the beginning of an ongoing feud that develops between the two men. There’s clearly not enough room on campus for both of their inflated egos. West soon moves in with Dan, who is looking for a roommate to share the rent, much to the chagrin of the latter’s girlfriend, Megan (Barbara Crampton), the Dean’s daughter who is unaware that his child is having sex with one of his students. West begins conducting experiments in the basement with his own reagent, reanimating dead animals before moving on to human cadavers at the university.

All of these ingredients are fine and dandy, but Re-Animator did not rise to cult status by special effects alone. The curse of a low budget actually fashions an intriguing cast of nobodies, and the stone-faced seriousness with which these actors engage the witty, death-induced dialogue adds a parodic twist to a sometimes melodramatic genre. Chief among them is Jeffrey Combs who plays West with just the right amount of weasely bravado, which he conveys so well with the clipped speech patterns of someone who doesn’t suffer fools gladly and says exactly what he means. I like the way he gives his dialogue a slightly melodramatic spin that never gets too cartoonish but chews just enough scenery to make his take on West very memorable. His character is obsessed with conquering brain death to the point of lunacy and it is fun to watch as his experiments become more ambitious and extreme.

I love the petulant way Combs’ West acts at Hill’s lecture, breaking two pencils at strategic points during the class until the exasperated professor tells him, “I suggest you get yourself a pen!” And then West lets him have it” You know, you should have stolen more of Gruber’s ideas then at least you’d have ideas.” David Gale nails the pompous Dr. Hill’s self-importance and feelings of superiority over everybody around him. He’s the bad guy you love to hate and his scenes with Combs are a lot of fun as we watch these two egotists butt heads.

Bruce Abbott has the unenviable task of playing the upstanding good guy Dan but thanks to the sharply written screenplay by Gordon, William J. Norris, and Dennis Paoli, he is given a substantial character to inhabit and we can easily relate to him. Dan becomes more conflicted as the film progresses and he finds himself caught up in West’s schemes to conquer death. Abbott may not get the most memorable dialogue to spout but he grounds the film with his everyman character caught up in extraordinary circumstances. He also plays well off Combs’ mad scientist, acting as the voice of reason in an increasingly strange world. Abbott is particularly strong in the sequence where he and West reanimate a cadaver and things go badly. While West continues to rant and rave, already looking ahead to the next experiment, Dan goes into shock after having witnessed a dead body coming back to life and go apeshit on Dean Halsey, killing him. Dan reacts like any rational human being would in that situation and Abbott’s performance grounds the film at just the right moments so that we accept the more outlandish ones.

Genre darling Barbara Crampton (From Beyond) manages to make what is basically a damsel in distress role memorable with her spunky charm and beautiful looks, not to mention her courage, which is put to the test in the film’s most infamous scene where Dr. Hill’s reanimated severed head attempts to perform a sexual act on her while she’s tied up that has to be seen to be believed. Beyond that, Crampton does a nice job of conveying the emotional breakdown of Meg after Dan tells her about her father’s death and then has to accept his reanimated resurrection.

As Re-Animator progresses, Gordon continues to up the ante in terms of gory set pieces. In the first one, West is armed with a syringe of his reagent, from there he moves on to a dead cat and then deals with an ornery human cadaver with a bone saw, culminating in the final showdown between Dan and West and Dr. Hill and his small army of reanimated corpses, which gives the film’s dazzling makeup effects quite a workout. For a low-budget film, they are surprisingly excellent and it helps that the actors do a lot to really sell it.

The idea to make Re-Animator came from a discussion Stuart Gordon had with friends one night about vampire films. He felt that there were too many Dracula movies and expressed a desire to see a Frankenstein one. Someone asked if he had read Herbert West – Re-Animator by H.P. Lovecraft. Gordon had read most of Lovecraft’s works but that book had been out of print and so he read a copy of it at the Chicago Public Library.

Originally, Gordon was going to adapt Re-Animator for his theater company the Organic Theater and then, at some point, decided to make it as a horror film using the theater as a soundstage. However, the powers that be didn’t like the idea of him making a horror film and felt that he should be making an art film instead. Then, he and writers Dennis Paoli and William Norris decided to do it as a half-hour television pilot. The story was originally set around the turn of the century and they realized that it would be too expensive to be recreated and updated it to the present day in Chicago, using actors from the Organic Theater Company of which Gordon was a member. They were told that the half-hour format was not salable and so they made it an hour, writing 13 episodes. Gordon was then told that the only market for the horror genre was in feature films. He was soon introduced to producer Brian Yuzna by mutual friend Bob Greenberg, a special effects artist who had worked on John Carpenter’s Dark Star (1974).

Yuzna saw Gordon’s current play entitled, ER, about an emergency room and was impressed with the screenplay for the pilot and the 13 episodes. Greenberg and Yuzna convinced Gordon to shoot Re-Animator in Hollywood because of all the special effects involved. Once there, Yuzna made a distribution deal with Charles Band’s Empire Pictures in return for post-production services. The budget was set for just under a million dollars with Yuzna describing it as having the “sort of shock sensibility of an Evil Dead with the production values of, hopefully, The Howling.” For research, Gordon and Yuzna interviewed several pathologists and toured a morgue in Los Angeles. Once the actors were cast, Gordon took them on a tour of the Cook County morgue in Chicago to show them how the bodies were treated and how the people who worked acted. A lot of the film’s gallows humor came from the pathologists he met.

John Naulin worked on Re-Animator’s gruesome makeup effects and drew inspiration from “disgusting shots brought out from the Cook County morgue of all kinds of different lividities and different corpses.” He and Gordon also used a book of forensic pathology in order to present how a corpse looks once the blood settles in the body, creating a variety of odd skin tones. Naulin said that it was the bloodiest film he had ever worked on. In the past, he never used more than two gallons of blood on a film. On Re-Animator, he used 24 gallons of blood. The biggest makeup challenge in the film was the headless Dr. Hill zombie. Tony Doublin designed the mechanical effects and was faced with the problem of proportion once the 9-10 inches of the head were removed. Each scene had to use a different technique. For example, one involved building an upper torso that actor David Gale could bend over and stick his head through so that it appeared to be the one that the walking corpse was carrying around.

Re-Animator received positive reviews from critics back in the day. Roger Ebert gave the film three out of four stars and found it to be, “a frankly gory horror movie that finds a rhythm and a style that make it work in a cockeyed, offbeat sort of way. It's charged up by the tension between the director's desire to make a good movie, and his realization that few movies about mad scientists and dead body parts are ever likely to be very good.” The New York Times’ Janet Maslin felt that it, “has a fast pace and a good deal of grisly vitality. It even has a sense of humor, albeit one that would be lost on 99.9 percent of any ordinary moviegoing crowd.” In his review for the Los Angeles Times, Kevin Thomas praised Combs’ performance: “The big noise is Combs, a small, compact man of terrific intensity and concentration.” Pauline Kael herself raved about it: “It’s like pop Bunuel, the jokes hit you in a subterranean comic zone that the surrealists’ pranks sometimes reached, but without the surrealists’ self-consciousness.”

When Re-Animator came out there hadn’t been a good mad scientist movie in some time. The horror genre during the early to mid ‘80s had been dominated by the slasher franchises of Friday the 13th, Halloween and A Nightmare on Elm Street so Gordon’s film felt like a breath of fresh air. It went on to develop enough of a cult following to spawn two sequels – Bride of Re-Animator (1990) and Beyond Re-Animator (2003) – and a musical proving that Lovecraft’s original story continues to fascinate people. It may also be the age-old theme of science messing with things, like death, with disastrous results. The film features a battle between two brilliant men recklessly playing God without thinking about the consequences.

SOURCES

Brody, Meredith. “We Killed

‘Em in Chicago.” Film Comment. February 1987.

Doughton, K.J. “Stuart Gordon: Body of Work.” Film Threat. July 17, 2002.

Fischer, Dennis. “A Moist

Zombie Movie.” Fangoria. August 1985.

Thomas, Kevin. “Re-Animator” Los Angeles Times.

October 25, 1985.

Williams, Ross. “Stuart Gordon: King of the Gorehounds.” Film Threat. July 9, 2003.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)