After the massive commercial

success of Batman (1989), rival

Hollywood movie studios attempted to cash in by adapting other classic comic

strips from the 1930s and 1940s with the likes of Dick Tracy (1990), The Shadow

(1994), and The Phantom (1996) being

released in the early to mid-1990s. With the exception of Dick Tracy, all of them were box office flops. Mainstream audiences

were just not interested in retro action/adventure movies that paid tribute to

classic Hollywood cinema. So, why did Dick

Tracy succeed where these other movies failed?

Dick Tracy was an adaptation of the popular comic strip created by Chester Gould in the 1930s and featured the titular square-jawed police detective as he

tangled with a colorful assortment of villains. He solved crimes using the

latest gadgetry and advances in forensic sciences. Gould’s creation proved to

be very popular and continues to be published to this day despite Gould’s

retirement in 1977.

The film version was

produced, directed and starred Warren Beatty in the title role, while also

including his then-girlfriend Madonna, as well as Al Pacino, Dustin Hoffman,

and James Caan among many other notable character actors. With that kind of

star power, how could the film not garner advanced hype? It also helped that

Touchstone Pictures took a page out of the marketing techniques employed on Batman and aggressively promoted Dick Tracy with a video game, a

novelization and Madonna herself advertising it on her Blond Ambition World

Tour.

A lot was riding on this

film, not just for the studio, who invested millions of dollars, but also

Beatty, still stinging from the high-profile failure of Ishtar (1987) and who

hadn’t directed a film since the highly acclaimed Reds (1981). The gamble paid

off and Dick Tracy performed very

well at the box office, but fell short of the kind of figures Batman registered. While the story was

pretty standard stuff, Dick Tracy was

visually stunning as Beatty and his cinematographer Vittorio Storaro (Apocalypse Now) adopted the source

material’s primary color scheme, making it quite unlike any comic book

adaptation before or since.

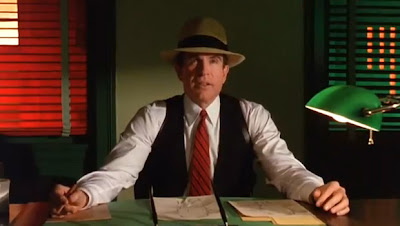

Dick Tracy (Warren Beatty)

investigates a gangland slaying. He knows who’s behind it – mob boss “Big Boy”

Caprice (Al Pacino) – but can’t prove it, much to his consternation. With the

help of his right-hand man, the vicious Flattop (William Forsythe), Big Boy

eliminates rival boss Lips Manlis (Paul Sorvino) and takes over his territory,

which includes his girlfriend, nightclub singer Breathless Mahoney (Madonna).

Meanwhile, Tracy’s girlfriend

Tess Trueheart (Glenne Headly) wants him to accept a desk job so that he’ll

stay out of trouble – something that he’s not crazy about or do any time soon,

at least not as long as Big Boy is at large. If that wasn’t enough, Tracy and

Tess are temporary guardians of The Kid (Charlie Korsmo), a scrappy boy who

witnessed the Manlis execution and is rescued from his abusive father by Tracy.

Warren Beatty does just fine

as the upstanding Dick Tracy. He certainly looks the part and does his best to

flesh out the character by developing a bit of a love triangle between Tess,

Tracy and Breathless. The Kid also shows a slightly vulnerable side to Tracy

and thankfully Beatty doesn’t fall into the trap of making the boy too cutesy

or annoying. A lot of people criticized Madonna’s performance and when she’s

paired up with the likes of veteran actors like Beatty and Al Pacino, she looks

out of her depth. For two people romantically involved in real life, Beatty and

Madonna have little chemistry together on film. Throughout, Breathless tries to

seduce Tracy with sexual double entrendes and provocatively revealing outfits

(including a see-through black negligee number that somehow got past the PG

rating). Madonna makes up for these moments in the song and dance routines

where, naturally, she is on more comfortable ground. Beatty does have slightly

more chemistry with Glenne Headly who plays Tracy’s girlfriend – a thankless

role that the talented actress does her best with, especially early on when

Tess and Tracy take care of The Kid in a charming montage that humanizes the

lawman a little bit.

Beatty must’ve pulled a lot

of favors that he accumulated over the years as so many of his contemporaries

and people he worked with back in the day play minor roles with most of them

buried under all kinds of prosthetic make-up. Al Pacino barks out most of his

dialogue in a scenery-chewing performance that would set the tone for many of

his portrayals in the ‘90s but Big Boy actually requires him to play it

over-the-top on purpose, which he does with typical gusto. The veteran actor

looks like he’s having a blast in the scenes where Big Boy bosses around

Breathless and her chorus line. One wonders if the little slaps he administers

to the sultry singer were improvised. Hell, in one scene alone you get to see Pacino

berate a room full of gangsters played by people like James Caan, Henry Silva

and R.G. Armstrong among others. Meanwhile, one of Tracy’s deputies is played

by Seymour Cassel and the police chief is portrayed by none other than the late

great Charles Durning. Beatty even cast two of his Bonnie and Clyde (1967) castmates, Michael J. Pollard and Estelle Parsons in supporting roles.

Beatty also stacked the deck

behind the camera with the great Italian cinematographer Vittorio Storaro and award-winning

production designer Richard Sylbert (Chinatown)

contributing to the film’s distinctive look. Not since Streets of Fire (1984), had there been such a stylized self-contained

retro-world where everything is heightened in a way that remained faithful to

its source material. Even the outfits that characters wear are color-coded. For

example, Tracy wears a yellow trenchcoat and hat while Tess wears a red outfit.

This also extends to the setting of a given scene. In the diner that Tracy,

Tess and the Kid frequent the seats are all red, the walls are all white and

outside the windows are saturated with green light. The end result is a visual

treat on the eyes and it’s all achieved through excellent cinematography,

production design, art direction, and old school visual effects like matte

paintings.

For the music, Beatty got Batman’s composer Danny Elfman to work

his magic and he delivers a suitably robust score even if it sounds like he

basically recreated the music he did for Tim Burton’s film. For the five period

authentic songs that Breathless Mahoney sings, Beatty enlisted none other than

the legendary songwriter Stephen Sondheim to write them and had Mandy Patinkin

and Madonna bring them to life in the film.

A common complaint among

critics was that Dick Tracy’s story

was a little on the simple side, but the comic strip was never that complex to

begin with and so keeping things simple stayed true to Gould’s creation. The one

minor quibble I have in this area is the over-abundance of bad guys, but Beatty

has said that he wanted to put as many of them in the film as possible in case

he didn’t get a chance to do a sequel, which, as it turns out, was probably a

wise move as another film seems highly unlikely.

Warren Beatty had

contemplated making Dick Tracy as far

back as 1975. He had fond memories of reading the popular comic strip as a

child. Producer Michael Laughlin owned the rights at the time, but gave up his

option when he couldn’t drum up any interest among Hollywood studios. In 1977,

director Floyd Mutrux and producer Art Linson bought the rights and got

Paramount Pictures involved. Over the years, many directors circled the

project, including Martin Scorsese, John Landis, and Richard Benjamin. At one

point, Clint Eastwood expressed an interest in playing Tracy, but Beatty had

the right to accept or reject the role before anyone else. However, even he

took convincing because the movie star didn’t think he looked like the character.

Beatty eventually realized that “nobody did. When I realized that I thought,

‘Well, maybe I can play this as well as the next guy.’”

Initially, Beatty had

difficulty finding a studio interested in bankrolling his project because they

were concerned with its commercial appeal and the movie star’s reputation as a

“control freak,” but he had gotten Chester Gould’s family’s blessing, which was

a good start. He almost made Dick Tracy

with Walter Hill when the director was in-demand during most of the 1980s, but

they differed on the approach to the material – Hill wanted to go the gritty,

realistic route, while Beatty envisioned a stylized look based on the comic

strip. Beatty bought the rights himself in 1985 and was soon armed with a

screenplay by Jim Cash and Jack Epps Jr. However, Beatty and Bo Goldman (One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest) rewrote

much of the dialogue. In 1988, he got backing from Disney, but had to work with

a $25 million budget.

Once Beatty got the go-ahead,

he had to figure out how to adapt Gould’s two-dimensional comic strip into a

live-action film. He felt that “it could be fun to go into another world – if

that world were carefully planned and carefully created.” With Dick Tracy, Beatty wanted to “look at a

picture through a child’s eyes, to get back to the feeling I had when I first

read Dick Tracy as a kid.” By

employing such a dazzling color scheme, Beatty figured that “If I could make Dick Tracy the centerpiece of a swirl of

color and plot, then maybe I could keep him from being terminally dull, which a

straightforward character like that is in danger of being.”

To this end, Beatty hired

three key collaborators to help him create this world: cinematographer Vittorio

Storaro, production designer Richard Sylbert and costume designer Milena Canonero (A Clockwork Orange) and

they all met at Beatty’s home during the summer of ‘88. Storaro wanted to go

with a standard aspect ratio in an attempt to mimic the comic strip panel.

Beatty told Storaro that the look of the film would be influenced by the late

1930s when Gould started Dick Tracy

and asked him to study the Bertolt Brecht opera, Rise and Fall of the City of Mahogonny. Storaro found that German

expressionist artists like George Grosz and Otto Dix best defined the art of

the ‘30s and inspired Gould’s drawings.

Sylbert drew inspiration from

‘30s era Chicago and adhered to the source material’s generic look with homes

devoid of anything but permanent fixtures and costumes kept basic and

repetitive. The idea was to reduce the sets to their most basic iconography.

Such a stylized world required filming the entire picture on the Universal

Studios back-lot where the filmmakers could create their world from scratch,

hiring visual effects artists Michael Lloyd (The Lord of the Rings trilogy) and Harrison Ellenshaw (Tron) to create 57 matte paintings on

glass that were then optically merged with the live-action.

Canonero was the one who

proposed that the film stick to a primary color palette. Another important

element was the make-up effects. To create the elaborate make-up of the various

gangster Tracy battles in the film, the make-up artists created drawings of the

characters and then hired sculptors to make models of each character. The

actors portraying each one of these characters had a cast made of their face so

that the right make-up and prosthetics could be created.

Dick Tracy enjoyed mostly positive reviews from

mainstream critics. Roger Ebert gave it four out of four stars and felt it was

“one of the most original and visionary fantasies I’ve seen on a screen.” In

his review for The New York Times,

Vincent Canby wrote, “Unlike Batman, though, Dick Tracy is more than imaginative decor and the

sort of clever makeup that transforms ordinary actors into characters named

Pruneface, Flattop, the Brow and Little Face. The movie is a gentle whirlwind

of benign mayhem swirling about the staunch figure of Mr. Beatty's Tracy. As

both the director and the star of the movie, Mr. Beatty is remarkably

generous.” The Globe and Mail’s Jay

Scott wrote, “Unlike the pretentious Batman, Dick Tracy doesn't attempt to find depth in the heroic machinations of a two-dimensional

figure: it seeks simply to turn the

famous cut-out into an iridescent icon.” USA

Today gave it three-and-a-half out of four stars and Mike Clark wrote,

“Beatty, though, has taken Dick Tracy to the next level: a Sunday strip.

This means color, additional artifice, and the further suspension of disbelief.

And even though Batman's Tim Burton

is a better filmmaker than Beatty will ever be, Dick Tracy is the movie – of all screen attempts –

that most convinces me I'm watching a live-action cartoon.”

However, Entertainment Weekly

gave the film a “B-“ rating and Owen Gleiberman wrote, “Dick Tracy is an honest effort but finally a bit

of a folly. It could have used a little less color and a little more flesh and

blood.” In her review for the Washington

Post, Rita Kempley wrote, “Dick Tracy is

an ambitiously vainglorious effort, expensive, beautifully appointed, but at

its core empty as a spent bullet. It asks us to read these comics without a

grain of salt or a pinch of irony. Popping around in that floppy designer

trench coat, Beatty looks more like the fashion police than a gangbuster. For

that matter, he is the director as haberdasher in this color-coded clotheshorse

of a movie.”

Along with Sin City (2005), Dick Tracy is one of the most visually stunning comic book

adaptations ever committed to film and one that anticipated similarly

hermetically-sealed cinematic fantasy worlds like the one the Wachowski

brothers created for Speed Racer (2008).

If the goal of movies, like this, is to take us away to a fantasy world, then Dick Tracy succeeds admirably. It has a

look and atmosphere all its own. Sadly, a sequel has not happened as Beatty

spent years in court with the company that own Gould’s strip who tried to wrest

back the film rights. Beatty recently retained them and has expressed an

interest in doing a sequel, but isn’t he too old to play Tracy now? Only time

will tell.

SOURCES

Ansen, David. “Tracymania.” Newsweek.

June 24, 1990.

Emerson, Jim. “Beatty Breaks

the Rules in Dick Tracy.” Orange

County Register. June 10, 1990. Pg. L08.

Guthmann, Edward. “Warren

Beatty Speaks.” San Francisco Chronicle. June 10, 1990. Pg. P20.

Koltnow, Barry. “Back with a

Simple Vision.” Orange County Register. June 10, 1990. Pg. L06.

Lowing, Rob. “Beatty’s Last

Chance.” Sun Herald. June 3, 1990. Pg. 6.

Staff. “Strip Show: The Comic

Book Look of Dick Tracy.” Entertainment

Weekly. June 15, 1990.

---Barbara-Stanwyck-740949.jpg)