“Audiences will come to

see something that has been invented by Bo. She is a happening, not really an

actress.” – John Derek

Sometimes

the making of a movie is a more interesting story than the movie itself. There

are legendary tales of runaway productions plagued by the clashing of egos,

extravagant spending or unforeseen acts of nature. Such is the case with Tarzan, The Ape Man (1981), a vanity

project directed by John Derek to promote the “talents” of his wife Bo Derek

who, for a short time, was a sex symbol thanks to the critical and commercial

success of 10 (1979). John managed to

convince MGM to back his “vision” of the Tarzan story from Jane’s

point-of-view. With Bo known more for her stunning looks than her acting chops,

how could this go wrong? Plenty. The Dereks’ hubris knew no bounds as they

managed to alienate the film crew, the Edgar Rice Burroughs estate, and the

studio. Predictably, the movie was savaged by critics but people saw it anyway

and it was a commercial success. The movie itself is incredibly inept on all

levels. What is interesting is the story about how it got made with the Dereks

exerting an unusual amount of control over the production.

The

character of Tarzan was created by Edgar Rice Burroughs and first appeared in

print in 1912. Son of a British lord and lady that were stranded on the east

coast of Africa by mutineers, as an infant Tarzan was raise by an ape tribe. Once

he became an adult, Tarzan crossed paths with Jane Porter, a young American

woman who, along with her father and others, had been marooned on the same

jungle area as Tarzan. The stories proved to be very popular and this led to

adaptations in film, radio and television over the years. MGM bought the film

rights in 1931 for the tidy sum of $100,000 and didn’t let it lapse for

decades, much to the chagrin of the Burroughs family.

In 1980,

actor-turned-director John Derek announced that he would remake the 1932 movie,

Tarzan the Ape Man, promising a

“sensual, erotic” update with his wife Bo starring (as Jane) and producing. Tired

of being exploited by other filmmakers, she decided it was okay to be exploited

by her husband and only make movies with him where she could do nudity on her

own terms. For the Burroughs estate this was the last straw and they charged

MGM with copyright infringement and sought unsuccessfully to block the release

of the movie. They were upset that the Dereks’ project would steal the thunder

from a long-delayed deal the estate had with Warner Brothers to make an

officially-approved $15 million adaptation. The Burroughs family lost on both

counts and filming went ahead as scheduled.

At the

time, Bo said that their intention was to tell a story “that was bigger than

life – something with the magic and fantasy that 10 had been. We wanted the story to be corny, romantic and more

absurd than 10.” If the final product

is any indication, they were successful in their goal. According to Bo, it was

John that came up with the idea of telling the story from Jane’s perspective

instead of Tarzan’s: “She has the perfect male who can’t talk, isn’t

sophisticated enough to think he is superior to her and doesn’t have any credit

cards.” John acted as his own hype man: “We are putting ourselves on the line

in this one, arrogantly saying, ‘We know best and we can do it better.’”

After

looking at the 1932 movie, famously starring former Olympic swimmer Johnny

Weissmuller, the Dereks realized that “we didn’t need to change anything to

suit our idea: it really had been Jane’s story all the time.” They set about

writing the screenplay with Gary Goddard, known more for his work on theme parks,

who wrote it in two weeks. In a controversial move, the resulting script

reduced Tarzan’s dialogue to a few grunts (he gets even less than that in the

finished movie). The Dereks went back to Burroughs’ stories for inspiration,

claiming that no one could have possibly taught Tarzan to speak English with

his parents dead and raised by great apes.

After the

financial success of 10, MGM wanted

to get in the Bo Derek business and agreed to finance John’s vision for a new

Tarzan movie. Right from the get-go the Dereks asserted their authority when

they refused the studio’s offer to shoot the movie in a Hollywood safari park.

They told the studio that they “would not film in a jungle Disneyland.” In June

1980, the Dereks spent two weeks scouting locations up the Amazon but found it

“too dark and too dense.” Kenya was not right either as they couldn’t get close

enough to the animals. They finally decided to film in Sri Lanka for the jungle,

and the Seychelles Islands, 1,868 miles away, for the sea, the beach and the

high cliffs they wanted. Understandably, the studio balked at expensive

location shooting but according to John, “’We’ll leave the country and shoot

the movie in some faraway place and John will direct and everyone can shut

up.’”

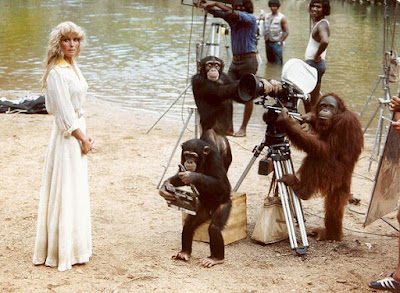

The

Dereks flew out to Sri Lanka on January 12, 1981 with a film crew of 23, a lion

named Dandi, an orangutan known as C.J., three chimpanzees, two Irish

wolfhounds and an 18-foot python they recruited from Thailand. Lee Canalito, a

27-year-old boxer-turned-actor standing 6’4” tall and weighing 280 pounds, was

cast as Tarzan. His claim to fame was appearing as Sylvester Stallone’s brother

in the ill-fated Paradise Alley

(1978).

Problems

occurred right away when the Dereks foolishly decided to spend their first

night in a tent in the jungle instead of the hotel with the crew in order to

get in the spirit of the story. They were soon driven out by mosquitos. They

should’ve taken this as an omen. For the shoot, the Dereks ordered 150

elephants and on the first morning they only needed two. The problem? No one

had ordered the elephants and it would take a week for them to walk to the

location.

By their

own admission the Dereks berated their crew who weren’t impressed with Bo and

John’s management skills. She said, “I knew some of them weren’t going to last

very long – and they didn’t. So every day, as people goofed or didn’t do their

jobs – I said, ‘Walk!’ And they did.” Bo was flexing her producer’s muscle. “It

was the first time dealing with people twice my age who I had to fire. They had

made dozens of films. I hadn’t. But getting rid of someone wasn’t really

difficult.” In the first 15 days of principal photography, Bo fired 15 of the

23 crew members, including Tarzan himself. According to Bo, “Lee had a

beautiful quality with a Michelangelo face but he wasn’t the proud lord of the

jungle.” When he was cast, Canalito was overweight and the Dereks had sent him

to the gym to get fit. In the end, “when we saw the rushes; we realized there

just too much jiggling.” When MGM cabled the Dereks asking what replacements

they needed, they replied, “None. We’ll do it all ourselves.” Again, how could

this go wrong?

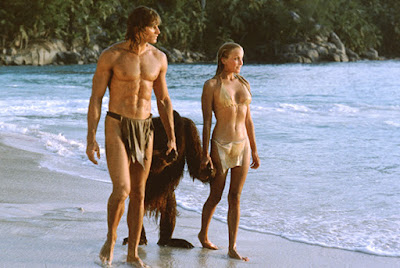

Sam

Jones, who appeared in 10 as Bo’s

husband, was briefly considered to be Tarzan. After auditioning by swinging

from a tree on a rope at a local Hollywood park, 26-year-old Miles O’Keeffe was

cast as Tarzan and flown out with 24-hours notice. The 6’3”, 200-pound man was

a former football player and psychology major, which of course made him the

perfect person to play Tarzan. He arrived in Sri Lanka, drove four hours

through the jungle and started filming immediately.

In the

wake of all the crew firings it became a family affair with Bo’s mother, who

had come along as a hairdresser, put in charge of wardrobe and makeup. Bo’s

sister Kerry helped as an assistant director. Even Bo’s best friend was given a

job. The remaining professional film crew ended up taking on ten jobs each.

According to the rookie producer everything was going well: “As people went we

had more fun, the problems were easier and we were getting better things on

film.” As anyone who has seen the final product, this comment is more than a

little surprising and speaks volumes of the couple’s hubris.

If the

Dereks had problems working with their crew, they didn’t have much luck working

with animals either. The lion they brought over was the wrong one and he didn’t

like working with chimps and the elephants. Apparently, he didn’t like working

with humans either. During the scene where Tarzan tries to drag Jane out of the

water and onto the beach, Dandi’s leash broke. The animal lashed out at Bo with

his paw, hitting her on the left shoulder which sent her sprawling back into

the water. He then hit her on the right hip but slipped before he could strike

again. Fortunately, the trainer and the rest of the crew intervened and subdued

the lion.

Bo did

get along with the orangutan but he got jealous when Tarzan started making love

with Jane. The same could not be said about the chimps. “They may look fun but

they are pigs to work with,” John said. The elephants were also a handful. The

younger ones wanted to play while the larger ones wanted to fight. During

filming they had to be tied to large trees that couldn’t uproot. Initially, the

python was afraid of Bo but as filming progressed it became friendly and even

tightened himself around her body during a scene. “I didn’t much care for the

wrestling with him in the water because then he would slide his body between my

legs and thighs.”

Tired of

being judged solely on her looks, Bo wanted to be taken seriously – hence

taking on the producer mantle. She wore many hats during the production,

claiming to have dealt with money problems, checking the number of packed

lunches that were needed and even acted as script girl for a while. She also

found out the local caterers were charging too much for lunch and fired them.

They were replaced by a messenger boy who was cheaper. John said of his wife, “Audiences

will come to see something that has been invented by Bo. She is a happening,

not really an actress.” Half of that sentence is accurate.

The

production incurred more headaches when moving from Sri Lanka to the Seychelles

Islands. Lions need jumbo jets to travel in. The only plane available was a 707

so John put the animal on a 747 out of Seychelles via London – a round trip of

11,663 miles. Filming mercifully wrapped on March 11, 1981. Miraculously, the

movie finished on schedule (48 days) and on budget ($6.6 million).

The

controversy continued as the Burroughs estate took MGM to court claiming that

“Tarzan is nothing more than a spear carrier,” and Jane, “in sexual matters she

is now the aggressor in a sense…The walking by Jane topless for long stretches

seems pervasive.” The estate also objected to the “suggestion of sexuality”

between Jane and her father and the “rubbing of Jane’s breasts” that took place

in a scene where she was “leaning on all fours” in preparation for being raped

by the Ivory King (Steve Strong). The estate also objected to a moment where a

chimp “actually kisses her breast” and a scene at the end of the movie in which

Tarzan, Jane and an orangutan “are almost simulating sexual activity.” The

Burroughs estate claimed that the original 1931 license meant that all Tarzan

films were intended for family entertainment and MGM violated the deal by

allowing extensive nudity in the Dereks’ movie.

The judge

presiding over the case screened the 1932 film, a 1954 remake with Denny Miller

and ordered cuts in four sequences. The Dereks refused to make them so MGM did

and resubmitted the movie to the judge who demanded additional cuts. He was

finally satisfied after three minutes and six seconds were removed. An outraged

John proclaimed, “Tarzan should be so lucky as to be made by us.” He fumed

about the cuts: “Ninety percent of Bo’s nudity will be cut out. If that’s not

censorship, I don’t know what is.” In protest, Bo went on Los Angeles

television to announce that she and John were giving up their 10% of the gross

and promised to contribute the money to saving gorillas endangered by poachers

in Zaire.

It is

safe to say that film critics were not kind to Tarzan, The Ape Man. Roger Ebert gave the film two-and-a-half out

of four stars and wrote, "The Tarzan-Jane scenes strike a blow for noble

savages, for innocent lust, for animal magnetism, and, indeed, for soft-core

porn, which is ever so much sexier than the hard-core variety." In his

review for The New York Times,

Vincent Canby wrote, "To describe the film as inept would be to miss the

point, which is to present Mrs. Derek in as many different poses, nude and

seminude, as there are days of the year, all in something less than two hours.

She is a magnificent-looking creature...However, as an actress she displays the

sort of fausse naivete that is less erotic than perfunctorily calculated, in

the manner of an old-fashioned, pre-porn-era stripteaser who might have started

her act dressed like Heidi." The Washington

Post's Gary Arnold wrote of John Derek's direction: "His approach to

the mating of Tarzan and Jane is so revoltingly coy and his filmmaking style so

inertly picturesque, like an arthritic imitation of The Black Stallion, that the movie is no more titillating than two

hours of patty-cake."

After all

the dust had settled, a bitter John called Hollywood “a hellhole,” claimed MGM

“failed me,” said that the Burroughs estate was “arrogant and sue-happy,” the

judge “made the Constitution a joke,” and felt that the press was “out to get

us.” He had to feel, however, somewhat vindicated by the box office results as

Tarzan made $36.5 million off a $6.6 million budget, but the damage had been

done within Hollywood. Effectively burning his bridges, he made Bolero (1984) for Cannon Films once

again starring Bo, which, in addition to being mired in production problems,

was a critical and commercial flop. They made one more film together – Ghosts Can’t Do It (1989), which

effectively killed off his filmmaking career. Bo continues to act in movies and

T.V. with her most significant role as Brian Dennehy’s trophy wife in the Chris

Farley/David Spade comedy Tommy Boy

(1995).

The

Burroughs’ estate got their classier, more faithful Tarzan film three years

later with the unwieldly titled, Greystoke:

The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes (1984), starring then-unknowns

Christopher Lambert and Andie MacDowell, which, despite its talent behind the

camera (director Hugh Hudson, screenwriter Robert Towne & make-up effects

artist Rick Baker), didn’t exactly set the box office on fire. Hollywood

continues to try to adapt Edgar Rice Burroughs’ most famous creation with John

and Bo Derek’s version serving as a cautionary tale of giving too much creative

control to filmmakers that clearly can’t handle it.

SOURCES

Harmetz,

Aljean. “Tarzan was the Star Once, And Not Bo Derek.” The New York Times.

June 10, 1982.

Hawn,

Jack. “Tarzan Publicity a Blessing

for Some.” Los Angeles Times. July 25, 1981.

Kelly,

Sue & David Wallace. “Too Wild?” People. July 27,1981.

Lewin,

David. “Bo Derek Takes to the Jungle to Bring Tarzan Back Alive.” The New York Times. July 19, 1981.

It makes me wonder how in the hell did the Dereks get funding for their crappy films. Under other filmmakers, Bo would be able to display her acting limitations in a film like Tommy Boy but knew what they needed and that was it. John Derek thought he was an artist. Nope, porno filmmakers are Picasso compared to him.

ReplyDeleteLOL! I think John was able to cash in on the buzz from Bo's appearance in 10. Their arrogance is what really gets me about all this. Well, they certainly got their egos held check on this one.

Delete