BLOGGER'S NOTE: This post is part of the Raimi Fest over at the Things That Don't Suck blog. There are all kinds of fantastic submissions going on, check it out!

Ever since Clint Eastwood's film Unforgiven (1992), the western has enjoyed a lucrative revival in Hollywood. That film's success paved the way for a whole slew of new takes on the genre from the traditional (Tombstone) to the gimmicky (Posse), with homages to all the old masters — most notably John Ford. However, no one had tried to pay tribute to Sergio Leone and his colorful Spaghetti Westerns (with the exception of Alex Cox’s surreal ode, Straight to Hell) that were wild, often surreal explorations of the western genre. No one that is, until Sam Raimi's film, The Quick and the Dead (1995) was released.

Raimi, best known for turning the horror genre upside down with his Evil Dead trilogy, was the ideal filmmaker to re-visit the Spaghetti Western. Like Leone, Raimi is not afraid to inject his own unique style into a film with the intention of breathing new life into a tired genre. Leone did this first with the western and later, the gangster film, while Raimi chose the horror film before tackling the western. The result: The Quick and the Dead is a playful, entertaining film that doesn't aspire to do anything more than take the viewer on a thrilling ride.

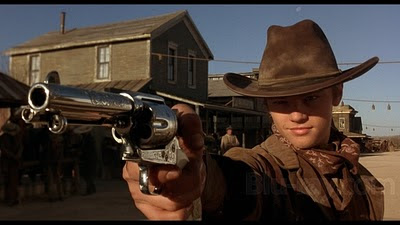

Essentially a series of shoot-outs, The Quick and the Dead distracts us from this simple concept with a twisted tale of revenge. Enter a mysterious woman (Sharon Stone) who is not only quick with her gun but with her snappy comebacks to snide remarks. She soon finds herself in the sorry excuse of a town named Redemption (you can almost cut the symbolism with a knife) conveniently before the start of its annual quick draw contest.

The competition throws all sorts of colorful characters into the mix: from Ace Handlen (Lance Henriksen), a preening card player and a crack shot, to The Kid (Leonardo DiCaprio), a young upstart who is as cocky as he is fast with a gun. To make the whole spectacle a little more interesting, the town's sheriff, John Herod (Gene Hackman), forces Cort (Russell Crowe), a lethal killer who used to ride with the lawman, into the contest. However, Cort has given up killing and turned into a repentant preacher with his lack of bloodlust adding a bit of variety to the proceedings.

The contest is run by Herod, a truly evil man, who delights in keeping the town under his tyrannical boot heel. It soon becomes apparent, however, that the contest isn't the only reason that Stone's character has arrived in this town. The competition serves as a convenient excuse for her to exact a little revenge and also for us to watch these wild personalities square off against one another.

The Quick and the Dead was a refreshing change of pace for filmmaker Sam Raimi. He had just survived an exhausting and often frustrating battle with Universal Studios over Army of Darkness (1993), the last film in his Evil Dead trilogy. His budget had been cut back considerably, to the point where Raimi and the film's star Bruce Campbell were forced to use their own money to finish the film. To make matters worse, critics and audiences alike subsequently panned Army of Darkness. Raimi viewed his new project as a way of putting this horrendous experience behind him.

But he was not the first choice to direct The Quick and the Dead. Simon Moore, a British screenwriter, wrote the script and intended to direct the film himself. However, the producers had other ideas when Sharon Stone came on board as one of the stars and a co-producer as well. She was great admirer of Raimi's work and recommended him as director. "He was the only person on my list. If Sam hadn't made this movie, I don't think I would have made it," she said at the time of its release.

Raimi accepted the job for a number of reasons. Up until that time, he had always been known primarily as an independent filmmaker working outside of the system. Raimi viewed this new project as his first Hollywood film with big name stars. "So it was time to see what it would be like to make a big Hollywood movie. It had always been a dream of mine, but I'd never done it." On another level, he saw this film as his homage to one of the masters of the western, Sergio Leone. No one had attempted to pay tribute to this particular filmmaker and Raimi thought it high time that someone did. As he commented in an interview with Cinescape magazine, "the current genre cycle, the 'Spaghetti Western,' which was Leone's cheesier, less-classy version of the big studio Western, hasn't really been re-explored. This script really hit upon that, updating it with a female lead and a different set of values."

What could have been just another novelty twist on the western is transformed by Raimi's Gonzo style into a slick film filled with dramatic slow motion shots, adrenaline-fueled zooms, tracking shots with unusual perspectives, and extensive usage of deep focus photography that resembles a demented Orson Welles on speed. This rather showy excess of style playfully sets the tone of the film between parody and seriousness to the point where you are never quite sure which side of the fence the film is on. This was Raimi's intention from the beginning as he saw this extravagant approach "as entertainment for the audience. This is a fun, entertaining Western for a '90s crowd."

Raimi's approach also keeps the film interesting to watch. In what is fundamentally a picture built around a series of shoot-outs, he keeps things fresh and exciting by filming each significant showdown in a different style. Raimi’s wild approach also gives The Quick and the Dead an almost surreal quality: we get an unusual perspective shot through a huge bullet hole left in one gunslinger's head that seems almost cartoonish in nature (only to be recycled in the director’s cut of Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers). The bad guys are photographed at dramatically low angles as they chew up the scenery with their sneering, dirty looks and obvious contempt for anything decent. Pathetic fallacy also plays a large role in the film. When a fierce storm of biblical proportions hits the town, sure enough something rotten is bound to happen. Of course this all seems like some sort of pat cliché, but there is a playful quality and chutzpah on Raimi's part to use every camera trick and technique in the book, that gives the film real charm and makes it worth watching.

Another reason why The Quick and the Dead is so watchable lies in the fine group of actors that assembled to make this film. It’s a good blend of big name, marquee value stars like Sharon Stone, Leonardo DiCaprio and Gene Hackman, mixed with strong character actors like Lance Henriksen and, at that time, Russell Crowe, who just starting out in Hollywood. Even though most critics admired Stone’s turn as a no-nonsense gunslinger that ably holds her own against any man, I found Crowe’s tortured killer turned preacher to be the real standout performance of the film. You can almost feel the pain and frustration boiling inside Cort as Herod forces him to kill time and time again, even though he has renounced his violent ways. Crowe doesn’t have nearly the amount of screen time that Stone, DiCaprio or Hackman have, but he makes every scene that he’s in count by playing against type — his character is quiet and reserved when everyone else threatens to go over the top with their performances.

The Quick and the Dead wasn’t all that well-received by mainstream critics when it first came out. Roger Ebert gave it two out of four stars and wrote, “As preposterous as the plot was, there was never a line of Hackman dialogue that didn't sound as if he believed it. The same can't be said, alas, for Sharon Stone, who apparently believed that if she played her character as silent, still, impassive and mysterious, we would find that interesting.” In his review for the Los Angeles Times, Kenneth Turan wrote, “The Quick and the Dead is showy visually, full of pans and zooming close-ups. Rarely dull, it is not noticeably compelling either, and as the derivative offshoot of a derivative genre, it inevitably runs out of energy well before any of its hotshots runs out of bullets.” The New York Times’ Janet Maslin wrote, “Suffice it to say that Ms. Stone's one tactical mistake, in a film she co-produced, is to appear to have gone to bed with Mr. DiCaprio's character … This episode has next to nothing to do with the rest of the story. And a brash, scrawny adolescent who is nicknamed the Kid can make even the most glamorous movie queen look like his mother.” In his review for the Washington Post, Desson Howe also criticized Stone’s performance: “Stone seems to conceive of acting as a series of fixed facial expressions. She goes from one to another — two in all — like someone playing with Peking opera masks … Suffice it to say, there hasn't been acting this mechanical since Speed Racer.” Finally, Entertainment Weekly gave the film a “C” rating and Owen Gleiberman wrote, “Of course, the superficiality of the characters wasn't a problem in Raimi's other films; those pictures reveled in their lurid cartooniness. Perhaps he's trying to outgrow his brazenly adolescent style, but if so, he picked the wrong genre in which to do it.”

The Quick and the Dead has become something of a forgotten film in Raimi’s canon. Not weird enough for his hardcore fans and too strange for the mainstream, it has been relegated to cinematic limbo. I think it is time to re-evaluate this film. The Quick and the Dead may not have anything profound to say about the human condition but so what? That's not the film's goal. It serves as a piece of escapism, to make one forget about the problems of the real world and enter a fantastic realm filled with vivid characters and exotic locales that only the power of film can deliver. And on that level, Raimi’s film is a success.