In a New York Times article about Night

Falls on Manhattan (1996), the fourth film in Sidney Lumet’s police

corruption quartet, Edward Lewine observes that the central question in these

films is can a good person remain good within the system? In Serpico (1973), Frank (Al Pacino) starts

off as a clean-cut recruit fresh from the academy and is immediately faced with

accepting payoffs from local criminals. In Q

& A (1990), Al Reilly (Timothy Hutton) prosecutes his first case

knowing that an esteemed cop (Nick Nolte) is dirty. In Night Falls, Sean Casey (Andy Garcia) is an assistant district

attorney that must choose between adhering to the law and releasing a cop

killer or making a dishonest deal to keep him in prison.

In Lumet’s masterpiece, Prince of the City (1981), corrupt

police detective Daniel Ciello (Treat Williams) tries to redeem himself by

ratting on his fellow police officers. As Lumet said in an interview, “The

picture is also about cops and how pressured they are, what they have to live

with day in, day out and how they try to keep some sort of equilibrium, whether

it’s staying honest or not becoming cynical.” This is the central thesis for

his police corruption quartet, realized so masterfully in this ambitious,

sprawling film with its 130 locations, 280 scenes and 126 speaking parts, all

of which Lumet handles with the assured hand of a consummate professional.

Danny is the leader of a

team of narcotics detectives that work in the Special Investigations Unit of

the New York City Police Department. They are a tight crew that work mostly

unsupervised and hang out together in their off hours with their families. They

are known as “Princes of the City” because of their impressive reputation for

busting crooks. They also skim money from said criminals and give informants

drugs in exchange for information. These guys live by the credo, “The first

thing a cop learns is that he can’t trust anybody but his partners…I sleep with

my wife but I live with my partners.”

Lumet has several scenes

that show the camaraderie between Danny and his partners. They have a shorthand

and joke with each other like life-long friends. There’s an ease and

familiarity to these scenes that is believable. The filmmaker knows how cops

talk to each other and how to depict it authentically. We often feel like flies

on the wall, observing the conversations that only occur behind closed doors.

Lumet does just enough to humanize Danny and his crew by showing them at work

and with their families in unguarded moments, which demonstrates that, in many

respects, they are regular working guys.

Danny and his crew live well

off the spoils of their busts and carry themselves with confidence and swagger

as typified by Danny’s arrogance. It’s the way he carries himself and the

belief that he and his crew are untouchable. Lumet illustrates this in a scene

where Danny helps a dope-sick informant in the middle of the night by busting

another junkie and giving the stash to his stoolie. He takes the junkie back to

his home – a grungy, squalid hovel – and listens to him beat his girlfriend (a

young Cynthia Nixon) for shooting up his stash. The look on Danny’s face says

it all, as he feels ashamed at what he’s done. The shame is eating him alive,

so much so that he spills his guts to Richard Cappalino (Norman Parker) and

Brooks Paige (Paul Roebling), federal prosecutors investigating police

corruption. It’s interesting that Danny’s junkie brother (Matthew Laurance),

who points out that he’s no different than the crooks he busts, initially

convinces him to approach Internal Affairs, but it isn’t until he listens to

one of his informants beating his girlfriend that he commits to ratting out

dirty cops.

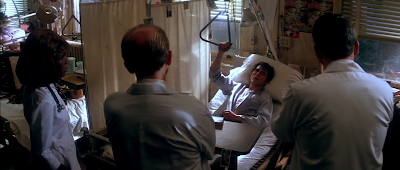

The scene where Danny tells

them what he knows is a riveting one as Treat Williams starts off cocky,

chastising these men for going after cops and then comes apart at the seams as

he tells them how it is for cops on the streets. The actor unleashes all of

Danny’s anger and frustration as he ends up breaking down by the end of the

scene. Guilt-ridden, he decides to work with Internal Affairs and break up his

team but with understanding that he’s not going to rat out his partners. The

rest of the film plays out the ramifications of his actions.

Lumet goes deep, showing how

Danny wears a wire, recording meetings he has with dirty cops and crooks. He

loves it, getting off on the adrenaline rush of the risk of being caught. The

scene where Danny is almost discovered by a dirty cop and a crook is full of

tension as these guys are ready to kill him. They take him at gunpoint for a

walk to the place where they’re going to do it. Danny tries to talk his way out

of it until a mafia guy (his uncle) vouches for him. The Feds shadowing him are

no help as they get lost trying to find him, as they don’t know the city. This

scene shows how close to getting killed Danny was and gives us an idea of how

much is at stake.

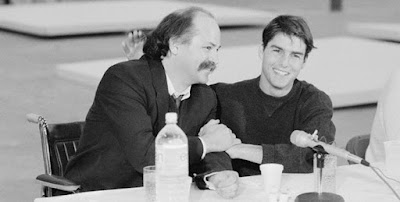

Aside from Hair (1979) and 1941 (1979), Williams hadn’t done much of note when he starred in Prince of the City, but Lumet saw something

in the actor that convinced him that he could carry a film of this size…and he

does. Williams does a brilliant job of conveying Danny’s arc over the course of

the film as he goes from cocky cop to a man that has lost it all.

The deeper Danny gets the

more scared he becomes as he not only has to avoid detection by fellow cops

that are corrupt and crooks while also dealing with Feds that alter his deal so

that he has to rat on cops that he’s friends with – something that he’s not

comfortable with doing. He’s torn between saving his own skin and ratting on

his friends. Lumet shows how this takes its toll not just on Danny but his wife

(Lindsay Crouse) and his two children. It gets so dangerous that the Feds take

Danny and his family up to their cabin in the woods under armed guard, scaring

his son and finally reducing his wife to tears one night when they’re in bed.

These are ordinary people trying to live under extremely trying conditions.

Writer Jay Presson Allen

read a review of Robert Daley’s 1978 book Prince

of the City: The True Story of a Cop Who Knew Too Much, bought and read it.

It was an account of Robert Leuci, an undercover narcotics cop in the Special

Investigation Unit in New York City from 1965 to 1972, making busts and cutting

deals with fellow cops. Some SIU detectives were the best in the city and had

the ability to choose their own targets and make major busts. They had their

own distinct style and wore more expensive clothes than other cops because they

had more money. In 1972, the Knapp Commission was looking into police

corruption. Leuci met with New York prosecutor Nick Scoppetta and couldn’t live

with the guilt of what he’d done, confessing his wrongdoings to the man. He

said, “I found myself in a place I didn’t want to be. I couldn’t tell the

difference between myself, my partners and the people we were investigating.”

Scoppetta convinced Leuci to go undercover and tape his friends and co-workers,

testifying against them. He went undercover for 16 months and the trials lasted

for four years. The end result saw 52 out of 70 members of the Special

Investigation Unit, of which he belonged, indicted, one went crazy and two

committed suicide.

She knew right away that it

was something Sidney Lumet should make into a film. When she inquired about the

rights, Allen discovered that Orion Pictures had bought it for $500,000 with Brian

De Palma set to direct and David Rabe was going to write the screenplay with

the likes of Robert De Niro, John Travolta and Al Pacino considered to play

Leuci. She didn’t think they could do it and called studio head John Calley and

told him, “If this falls through, I would like to get this for Sidney, and I

want to produce it, not write it.” He

agreed and she gave Lumet the book. He loved it but they had to wait until De

Palma’s attempt did not pan out. When this happened Lumet told Allen that he

wouldn’t do the film unless she wrote the script. She was tired and felt it was

too big of a job to take on: “It seemed like a hair-raising job to find a line,

get a skeleton out of the book, which went back and forth…all over the place.”

She agreed to Lumet’s proposal but only if he wrote the outline.

He proceeded to cut the book

up into sections starting with the ending. He highlighted the three critical

moments in Danny’s life: when he decides to reveal the names to his partner,

when the judges meet to decide whether they should indict him for giving false

testimony, and the discussion to retry the most crucial case he had to testify.

Afterwards, they sat down and went through the book and agreed on what were the

most essential scenes and characters.

Over the next two to three

weeks, Lumet wrote 100-handwritten pages, which Allen didn’t like but thought

that the actual outline was wonderful. It was the first time she had ever

written about living people, which she found daunting. She proceeded to

interview almost everyone in the book. Only then did she begin writing,

completing a 300+ page script in ten days! When it came to filming, she had the

book and all of her interviews to draw from if there was ever a question about

something in the script. Lumet compared the script to the writings of famed

journalist Norman Mailer: “It’s a news story that becomes fiction in the sense

that the dramatic situations are so strong.”

After the comedy Why Would I Lie? (1980) received bad

reviews and performed poorly at the box office, a frustrated Treat Williams

changed professions, getting a job flying planes for a company in Los Angeles.

Six months later, Lumet approached him about Prince of the City based on his work in Hair. He didn’t cast him, however, until after they spent three

weeks talking and going over the script. Finally, he had Williams read with the

rest of the cast and then decided to cast him as Danny. For research, Williams

hung out with cops at the 23rd precinct in New York City and went on

3 a.m. busts in Harlem: “I saw junkies pleading to go to the bathroom and

vomiting and shaking. You see people of the lowest end of humanity and you know

if they had a gun they’d probably try to kill the cops.” He also hung out with

Leuci and studied him: “Bob has a lot of tension in his shoulders. His toes go

in when his foot lands. His walk is in the movie.”

Prince of the City was one of Lumet’s most ambitious projects and he and his crew had to

be prepared: “We had to know the one-way streets, the traffic flows, the

various routes we could take to save time.” He had planned a shooting schedule

of 70 days and finished in 59 days. Lumet planned every camera movement and

angle ahead of time. He did not use normal lenses as he wanted to create an

atmosphere of “deceit, and false appearances,” and only used wide angle and

zoom lenses. In addition, the first half of the film featured lighting on the

background and not on the actors while in the middle of the film he alternated

between the foreground and the background, and the end of the film aimed the

lighting on the foreground only.

Roger Ebert gave Prince of the City four out of four

stars and wrote, “It is about ways in which a corrupt modern city makes it

almost impossible for a man to be true to the law, his ideals, and his friends,

all at the same time. The movie has no answers. Only horrible alternatives.” In

her review for The New York Times,

Janet Maslin wrote, “Prince of the City begins

with the strength and confidence of a great film, and ends merely as a good

one. The achievement isn’t what it first promises to be, but it’s exciting and

impressive all the same.” Pauline Kael was less impressed with the film: “The

film has a super-realistic overall gloom, and the people are so ‘ethnic’ and

yell so much that you being to long for the sight of a cool blond in bright

sunshine.”

As Prince of the City moves into its second hour, the grind of what

Danny is going through – the endless court appearances and the revolving door

of handlers – affects the viewer as well, wearing us down as we wonder, like

Danny does, when is this all going to end? By the end of the film, the system

uses and discards him after he’s served his usefulness. Williams manages to

make a sympathetic character but Lumet doesn’t let us forget that Danny was the

architect of his own demise. He ratted on fellow cops to save his own skin. He

lied in court to protect his ex-partners to avoid jail time.

Is Danny a hero? Did he do

the right thing? During filming, Lumet wrestled with his feelings about Danny

as an informant: “And I think that ambivalence is in the movie, and I think it

makes the movie better. Part of it was that it was very difficult for me to

separate political informing from criminal informing – a rat was a rat.”

Ultimately, Lumet leaves it up to the audience to decide how they feel about

the man and what he did. It’s a complex portrayal not just of the man but also

the legal system he works in. There’s no good guys or bad guys – only lots of

moral ambiguity.

SOURCES

Ciment, Michel. “A

Conversation with Sidney Lumet.” Sidney

Lumet: Interviews. Joanna E. Rapf. University Press of Mississippi. 2005.

Cormack, Michael. “From

Prisoner to Policeman.” The Globe & Mail. October 12, 1981.

Corry, John. “Prince of the City Explores A Cop’s

Anguish.” The New York Times. August 9, 1981.

Cunningham, Frank R. Sidney Lumet: Film and Literary Vision.

University Press of Kentucky. 2001.

Harmetez, Aljean. “How Prince of the City is Being

‘Platformed.’” The New York Times. July 18, 1981.

Hogan, Randolph. “At Modern,

Lumet’s Love Affair with New York.” The New York Times. December 31,

1981.

Kroll, Jack. “A New Breed of

Actor.” Newsweek. December 7, 1981.

Lawson, Carol. “Treat Williams:

For the Moment, Prince of the City.” The New York Times. August 18,

1981.

Lewine, Edward. “The

Laureate of Police Corruption. The New York Times. “June 8, 1997.

Myers, Scott. “How They

Write a Script: Jay Presson Allen.” Go Into the Story. May 31, 2011.

Scott, Jay. “Director Sidney

Lumet Fears for the Future of ‘Real’ Films.” The Globe & Mail.

August 19, 1981.

Zito, Tom. “The Prince Himself.” Washington Post.

October 2, 1981.