“When people say if you don’t love America, then get

the hell out. Well, I love America, but when it comes to the government, it

stops right there.” – Ron Kovic

Oliver Stone’s filmic prescience

is widely regarded by critics, students and the public at large. It hit is apex

with 1989’s Born on the Fourth of July,

a cinematic crystal ball, which anticipated the rise of Donald Trump’s divisive

“Make America Great Again” nationalism. Stone’s biopic traces the life of Ron

Kovic (Tom Cruise), from his beginnings as the quintessential all-American boy

proud eager to serve the country he loves and respects in the Vietnam War, to

being a disillusioned veteran, paralyzed in battle and how it led to his

anti-war activism. This film asks particularly difficult questions about what

it means to be American and has become even more relevant today than the year

it was released to critical and commercial success.

Ron Kovic’s voiceover

narration establishes a picturesque childhood, he and his best friends play

soldiers with other neighborhood kids. He grows up in the Norman Rockwell-esque

small town America of the 1950s. Born on

the Fourth of July is propaganda – but all is not what it appears; Stone

cleverly subverts it, showing us little cracks in the idyllic façade. As a

child, Ron idolizes the soldiers he sees with his family in a parade early on

in the film. This is tempered when one soldier visibly winces at the sound of firecrackers

and another is shown, arms lost in battle, a grim look on his face.

Stone’s multi-layered

patriotic imagery during the opening credits sequence is bathed in a sun-kissed

glow, courtesy of Robert Richardson’s stunning cinematography. Ron’s mother

(Caroline Kava) even calls him her “little Yankee Doodle Boy.” This is the land

of 4th of July fireworks, parades populated by beautiful

cheerleaders and where Ron is an exceptional athlete, hitting an in-the-park

home run as a boy. He lives in suburbia with a family that embodies the

American Dream.

As a teenager, he excels in

wrestling, being pushed to his limits by a coach whom has all the zeal of an

army drill sergeant. It is in these early scenes that we see the Tom Cruise we

all know – the ambitious go-getter, but Stone tempers this by showing Ron lose

an important match in front of his classmates, friends, and family. His

anguished expression – as boos ring out around him –foreshadows more painful

defeats to come.

Ron’s hero worship of the military

continues when he attends a presentation (a.k.a. a recruitment pitch) by the

United States Marines at his school. There is delicious irony as Ron looks

adoringly at the Marine speaking (played by none other than Tom Berenger) as if

the actor’s demonic soldier from Platoon (1986)

somehow survived, returning stateside to recruit young men to fight in the

Vietnam War.

Ron buys into it, eager to

serve his country as his father (Raymond J. Barry) did before him in World War

II. He wants to go and fight in

Vietnam and is even willing to die there (“I want to go to Vietnam – and I’ll

die there if I have to). His life is playing out like a stereotypical Hollywood

movie. He even rushes to the prom, in the rain, to declare his love for

girl-next-door-eseque Donna (Kyra Sedgwick) as “Moon River” plays over the gymnasium

speakers.

Ron’s idyllic youth comes to

a violent end once we see him in ‘Nam, his platoon accidentally slaughtering an

entire village. To make matters worse, he inadvertently shoots and kills one of

his own soldiers. He tries to own up to it but his superior (John Getz)

dismisses him. Where everything stateside was simple to understand – Ron always

took for granted that he knew what was expected of him. Vietnam is chaotic and

confusing, the enemy difficult to identify. As he did with Platoon, Stone immerses us in the sights and sounds of battle,

albeit in a more stylized depiction. Here, he employs more slow-motion, filters,

and skewed camera angles to show the disorienting effect of combat through

Ron’s eyes.

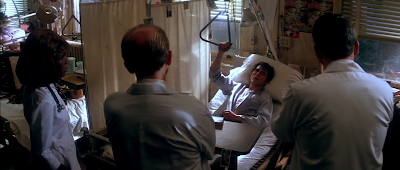

He is wounded in battle and is

shipped back to the Bronx Veterans Hospital where he finds out that he’s been

paralyzed from the chest down. Despite the absolutely appalling conditions

(rats scurrying between beds, interns shooting up in closets and Ron starring

at his own vomit for hours), he still believes in the American Dream and is

critical of the anti-war protestors he sees on television. He aggressively

attacks physical therapy, refusing to accept the doctor’s diagnosis that he’ll

never regain the use of his legs.

Cruise is particularly

effective in these scenes as he conveys Ron’s gradual disillusionment with the

system. He is slowly becoming dehumanized by the system that cares little about

him. Government cutbacks result in poor conditions and treatment that Stone

depicts in unflinching detail. Is this how our country honors those that put

everything on the line to serve their country?

Ron’s homecoming is a

heart-wrenchingly bittersweet one. On the surface, his family is happy to see

him – the heartbreaking emotions swell under the surface, conveyed in his

mother’s eyes when she embraces him, giving a brief, sad look that he is unable

to see. While his father goes on about the changes he’s made to the bathroom to

make it more accessible for his son, Ron only half-listens as he looks around

his old bedroom, lingering on a photograph of himself during his wrestling days

at high school. Stone shows Ron’s image reflected in the glass of the picture

frame, visually giving us a before and after of this man’s life.

Ron quickly picks up on how differently

people in the town look at him: “Sometimes I think people know you’re back from

Vietnam and their face changes, their eyes, the voice, the way they look at

you.” A family dinner breaks up when Ron’s brother (Josh Evans) leaves the

table, unable to stomach his brother’s patriotic rant. He participates in a

parade, much like the one he saw as a child and flinches at the sound of a

firecracker, like the veterans he once saw, and this time is faced with angry

protestors and other townsfolk; he begins to realize this is not his father’s

war.

At the rally afterwards, Ron

falters while making a patriotic speech as he experiences a flashback to ‘Nam.

Confused, he is “rescued” by childhood friend and fellow veteran Timmy Burns

(Frank Whaley). The relief that washes over him at the sight of a familiar face

is palpable. The scene between the two men afterwards is quietly affecting as

they share stories of their experiences on the battlefield. Timmy tells Ron

about the headaches he has – “I don’t feel like me anymore” – and his

frustration that the doctors don’t know how to help him. Cruise conveys

incredible vulnerability as Ron regrets the mistakes he made in Vietnam, how he

feels like a failure, and how badly he wants to regain the ability to walk.

This scene features some particularly strong acting from both men, defining

moments for both actors and the characters.

I like how Stone spends time

showing the moments and events that happen to change Ron’s views of the war. It

wasn’t just one incident but a series of them, most significantly an anti-war

rally where we can see the change of his way of thinking play over his face. Without

warning, cops move in and he watches, helplessly, as they beat protestors. At

last, Ron breaks down in his parents’ home, getting into a shouting match with

his mother as he finally lets out all of the anger and anguish built up inside

him about the war. He’s approaching rock bottom and Cruise conveys Ron’s hurt

in a raw and powerful way that is riveting to watch.

It isn’t until he goes to Mexico

– in a dust-up with a group of veterans in a bordello – that Ron has an

epiphany out in the desert with Charlie (Willem Dafoe), a fellow Vietnam vet.

They get into a heated argument about how many babies they killed over there.

Afterwards, exhausted, Ron says, “Do you remember things that made sense?

Things you could count on before it all got so lost? What am I gonna do, Charlie?”

This conversation, combined with visiting the graveside and confessing to the

parents of the American soldier he accidentally killed (in a painful,

gut-wrenching scene that Cruise gives everything he has), are the pivotal

moments that transform him into being an anti-war activist.

When Ron emerges on the

floor of the 1972 Republican National Convention in Miami Beach, speaking out

against the war and President Nixon administration, Ron has a cathartic moment,

finally finding a way to channel his anger and frustration. Once removed from

the convention, he’s almost arrested and roughed up, the police giving no

consideration for his physical condition. Undaunted, he uses his military training

to organize the protestors and continue on in a battle of a different kind.

One

month after Ron Kovic gave a speech at the 1976 Democratic Convention, his book

about his experiences before, during and after the Vietnam War was reviewed in The New York Times. It drew the

attention of movie producer Martin Bregman who bought the rights to the book.

He quickly realized that it didn’t have good commercial prospects as the

subjects of Vietnam and life as a paraplegic being its focal points. Kovic then

served as a consultant on a film about the same subject – Hal Ashby’s Coming Home (1978), starring Jon Voight,

who won the Academy Award for his performance. Universal Studios – who were

going to finance Born on the Fourth of

July – pulled their money and support. No other studio was interested and no

one wanted to direct it. All Bregman had was a screenplay written by a young

Oliver Stone, who clearly identified with Kovic’s experiences: “My story and

that of other vets is subsumed in Ron’s. We experience one war over there then

came home and slammed our heads into another war of indifference…and we all

came to feel we had made a terrible mistake.”

Bregman

found German investors willing to put up money for pre-production, hired Dan

Petrie (A Raison in the Sun) to

direct, cast Al Pacino as Kovic, with Orion Pictures distributing the film. A

few weeks before rehearsals were to begin, the foreign financing fell through

and the rights reverted back to Universal. Pacino had second thoughts and left

to make …And Justice For All (1979),

leaving Bregman $1 million in the hole and Stone depressed, his script without

a home. The latter promised Kovic that one day they’d make this film together

and became a filmmaker in his own right.

While

Stone wrote the script for Wall Street

(1987), Tom Pollock, then-president of Universal, took a look at the

filmmaker’s script for Born on the Fourth

of July and realized, “it was one of the great unmade screenplays of the

past 15 years.” He told Stone that the studio would make it for $14 million and

a major movie star as Kovic. After making Platoon,

Stone considered rewriting a script from 1971 based loosely on his own

experiences returning home from Vietnam but put it aside in favor of Kovic’s

story, which he felt had broader appeal.

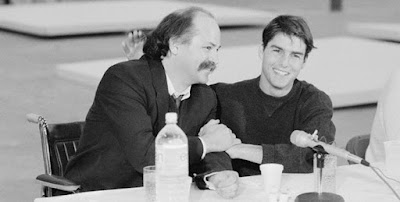

Stone

and Kovic considered Sean Penn, Charlie Sheen, Nicolas Cage, and ultimately

went with Tom Cruise. Stone met with him and told the actor he needed a movie

star to play Kovic and had a small budget to make it. Cruise, who had wanted to

work with Stone, accepted the challenge. He was drawn to the film as he felt it

was a personal passion project for Stone: “I thought it was almost his life

story, too, his Coming Home.”

The

young actor identified with Kovic’s working class ethic and his drive to become

the best: “I grew up hearing ‘no’s and can’ts’, but I pushed myself forward,

always looking ahead so I wouldn’t get stuck.” Stone was drawn to Cruise’s

all-American boy image: “I thought it was an interesting proposition: What

would happen to Tom Cruise if something goes wrong?” Furthermore, “I sensed

with Tom a crack in his background, some kind of unhappiness, that he had seen

some kind of trouble. And I thought that trouble could be helpful to him in

dealing with the second part of Ron’s life.”

Bregman

felt that Cruise was a safe choice and not strong enough an actor for the tough

material. Initially, Kovic agreed until he met Cruise: “I felt an instant

rapport with him that I never experienced with Pacino.” The two men talked for

hours and Kovic got very emotional. He remembered, “I felt like a burden was

lifted, that I was passing all this on to Tom. I knew he was about to go to

Vietnam, to the dark side, in his own way.” The actor remembers meeting the man

he would play on film and how he “really opened up to me.” Cruise knew this

would be a daunting role and felt ready after making The Color of Money (1986) with Martin Scorsese and Rain Man (1988) with Barry Levinson. “I

made it work one day at a time. If I looked at the mountain, it was just too

high.”

Stone

wasn’t immediately convinced: “Tom was cocky, sure he could handle everything.

But I wasn’t so sure…He was shaky at first, but we shot in continuity as much

as possible to show how, step by step, he began to understand.” To prepare for

the role, Kovic took Cruise to veterans’ hospitals where he spent days talking

and working with paraplegics. He hung out with Kovic in a wheelchair until it

became second nature. Cruise also read many books about the war, including

Kovic’s diary. Stone brought in his trusted military adviser Dale Dye to work

with Cruise and the cast on two separate week-long training missions. Dye

remembered that he “treated him no differently than I treated anybody else…A

big part of it was, of course, helping Tom Cruise get the mentality he needed

for the film.” They had to dig their own foxholes and live in them as well as

learn to handle a variety of weapons. Stone also brought in Abbie Hoffman to

talk to the cast about the peace movement in the 1960s. The legendary activist

even has a cameo in the film.

Principal

photography was a grueling 65-day shoot with 15,000 extras and 160 speaking

roles. Dallas doubled for both Long Island and Mexico. The production shot

10-12 hours a day in 100-degree heat. At one point, Cruise got sinusitis. Several

crew members fainted in the extreme climate. At one point, Stone became quite

sick. Focused on the film, he ignored the symptoms until they got in the way of

his work. He went to a local hospital in Dallas, underwent a panel of tests and

was given medicine. His condition, however, only worsened. The film’s

production coordinator called a local physician who had treated other crew members.

He recognized Stone’s symptoms as an allergic reaction to a particular kind of

pollen common in Dallas at that time of year.

Stone

challenged his crew to duplicate Long Island in Dallas on a small budget.

Several blocks of houses were given new looks and landscaped to recreate

Massapequa, 1957. Principal photography began in October 1988 with the

successful transformation of a southeast section of the city into a Long Island

neighborhood. Born on the Fourth of July

also saw Stone, for the first time, experiment with several different kinds of

film stocks: 16mm, Super 16 and 35mm. He combined footage shot for the film

with grainy, archival footage that was originally shot for network news in ’72

to recreate the veterans demonstrating at the Republican National Convention in

Miami Beach. This certainly wouldn’t be the last time as he continued to do so

with The Doors (1991), JFK (1991), Natural Born Killers (1994), Nixon

(1995), and U Turn (1997).

Filming

went on hiatus for the Christmas holidays, giving Stone an opportunity to edit sections

of the film. He realized that his vision for Born on the Fourth of July had expanded and he would need to shoot

more footage than budgeted. Stone went to Pollock and told him he needed an

additional $3.8 million. The studio executive was hesitant but after the

director showed him some edited sequences, he was given the money and allowed

to go ten minutes over the running time that was in his contract.

Cruise

had a particularly tough time with the scene where a sexually impotent Kovic

pays to be with a Mexican prostitute. Stone remembers the actor’s shyness:

“We

just kept shooting, working up to the place where Tom cries, thinking about

everything he’ll miss – certainly not from the joy of sex. On one take,

something happened inside him. Those tears came from someplace in Tom.”

Cruise

remembered, “I went to Oliver and I said, ‘I’m just not there. It’s just not

working.’ I remember feeling a lot of anxiety actually.” Stone told him to just

do the scene and not think about it. The actor did it and, in the process,

learned to let go. The two men clashed occasionally: “Tom is macho, aggressive,

male and he wants the best. Perfection is his goal and if he doesn’t achieve

it, his frustration is high.” Stone also clashed with the studio, nervous about

the film’s commercial prospects so he and Cruise gave up their salaries for a

percentage of the profits – a gamble that paid off exponentially.

Kovic

was so impressed by Cruise’s performance that on the last day of filming he gave

the actor his Bronze Star that he won in Vietnam. For Stone, he wanted the film

to “show America, and Tom, and through Tom, Ron being put in a wheelchair,

losing their potency. We wanted to show America being forced to redefine its

concept of heroism.”

More

conflicts arose between Stone and the studio during post-production. When it

came to editing the film, Stone felt that the ending needed to be reshot and he

also wanted John Williams to score the film. Cruise and Pollock agreed about

reshooting the ending but the executive did not want to spend the extra money

required to get Williams. In addition, he wanted to move up the release date to

Veterans Day instead of Christmas. This enraged Stone and he went to Mike

Ovitz, then-head of Creative Artists Agency, who wielded great power in

Hollywood, and got him involved. After a meeting with Pollock, Stone agreed to

shoot a new ending and Pollock agreed to both keep the original release date

and pay to have Williams create the score. Stone remembers, “It left a lot of

bad blood. I didn’t continue to work with Universal.”

Born on the Fourth of July received mixed to

positive reviews at the time. Roger Ebert gave the film four out of four stars

and wrote, “It is not a movie about battle or wounds or recovery, but a movie

about an American who changes his mind about the war…This is a film about

ideology, played out in the personal experiences of a young man who paid dearly

for what he learned.” Pauline Kael was much more dismissive: “Born on the Fourth of July is like one

of those commemorative issues of Life

– this one covers 1956 to 1976. Stone plays bumper cars with the camera and

uses cutting to jam you into the action, and you can’t even enjoy his

uncouthness, because it’s put at the service of sanctimony.” In his review for The New York Times, Vincent Canby wrote,

“It’s the most ambitious non-documentary film yet made about the entire Vietnam

experience. More effectively than Hal Ashby’s Coming Home and even Michael Cimino’s Deer Hunter, it connects the war of arms abroad with the war of

conscience at home.”

Entertainment Weekly’s Owen Gleiberman gave

the film a “C+” rating and wrote, “Tom Cruise tries hard, yet he’s fatally

miscast: He simply doesn’t have the emotional range to play a character

wallowing in grubby desperation.” In his review for the Washington Post, Hal Hinson wrote, “Born on the Fourth of July is nettlesome work. Stone has gifts as a

filmmaker, but subtlety is not one of them. In essence, he’s a propagandist,

and, as it turns out, the least effective representative for his point of

view.” Finally, Rolling Stone’s Peter

Travers wrote, “Stone has found in Cruise the ideal actor to anchor the movie

with simplicity and strength. Together they do more than show what happened to

Kovic. Their fervent, consistently gripping film shows why it still urgently

matters.”

There are people that are

patriotic and those that are nationalistic fused with fascism, twisted into

something so ugly that it doesn’t resemble what would be called patriotism, to

spawn the bastardization of what passes for democracy today. This film wrestles

with the definition of patriotism. The power of constitutional rights – most

pointedly, the right to assemble and freedom of speech – are both key to our

understanding about what it means to be American. It is not un-American to be

critical of the country when it has become an unjust place, when the landscape

has become an inhospitable place no longer nurturing the ideals upon which it

was founded.

Within the fabric of Born on the Fourth of July lies hope. We

hope that Kovic is not representing the lone man but the everyman. Hopefully,

we will all wake up to what is really happening, pick ourselves up and enact

change. This film is a rallying cry that needs to be sounded again, repeatedly,

unrelenting in its echo.

SOURCES

Chutkow,

Paul. “The Private War of Tom Cruise.” The New York Times. December 17,

1989.

Dutka,

Elaine. “The Latest Exorcism of Oliver Stone.” Los Angeles Times.

December 17, 1989.

Gabriel,

Trip. “Cruise at the Crossroads.” Rolling Stone. January 11, 1990.

O’Riordan,

James. Stone: A Biography of Oliver Stone.

Aurum Press. 1996.

.jpg)

.jpg)