Modern day fairy tales that

involve elements of magic realism are hard to pull off credibly in contemporary

cinema. With a few notable exceptions (see Field

of Dreams), this kind of film is not popular with mainstream movie-going

audiences as they have become increasingly jaded and cynical since the 1970s.

This may explain why Prelude to a Kiss

(1992) failed at the box office and was savaged by critics despite featuring

two very popular actors in the leading roles. At the time, Alec Baldwin had

established his leading man credentials with The Hunt for Red October (1990) while Meg Ryan became America’s

sweetheart thanks to When Harry Met

Sally… (1989). Putting these two together must’ve seemed like a no-brainer

and yet Prelude to a Kiss

underperformed. It certainly isn’t your typical romantic comedy, but for those

who become captivated by its bewitching atmosphere, it is a special kind of

film with a story that resonates long after it ends.

Based on Craig Lucas’ play of the same name, Prelude to a Kiss

starts off as a sweet romance between two people. Peter (Alec Baldwin) and Rita

(Meg Ryan) meet at a party. He is about to leave, but is coerced to stay by a

friend (Stanley Tucci) who introduces him to her. While Peter initially comes

across as a bespectacled, button-downed type (it’s endearing how the filmmakers

try to dress down the hunky Baldwin) while Rita comes across as a fun-loving

free spirit, dancing to “I Touch Myself” by the Divinyls. She’s all

touchy-feely while he tries to tell a lame joke.

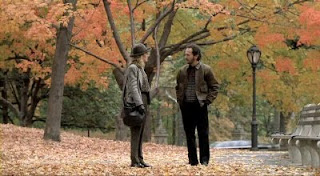

They get to talking and

there’s a wonderful looseness to the party scene as Peter and Rita have an

awkward meet-cute moment that feels genuine. It also helps that there is

terrific chemistry between Baldwin and Ryan. Their conversations early on in

the film are charming and witty as they touch upon subjects like him reading The White Hotel by D.M. Thomas, having

kids, her history of insomnia, and recounting his unhappy childhood due to his

parents’ divorce. The latter of which is told so well by Baldwin who has that

great voice that captivates Rita (and us). As a result, we don’t want these

getting-to-know-you scenes to ever end as they are so engaging and romantic.

They get serious enough that

Peter meets Rita’s parents (played charmingly by Ned Beatty and Patty Duke) in

a scene that starts off awkwardly as they good-naturedly mess with him,

culminating in a funny bit where her dad flexes a bulldog tattoo on his arm,

which Beatty plays with just the right eccentric spin. Things go swimmingly and

they decide to get married. In another part of the city, an old man named

Julius (Sydney Walker) decides to go for a walk and winds up on a train bound

for the suburb where Peter and Rita are getting married. He shows up and

mingles with the partygoers. At the reception, the elderly man approaches the

happy couple and when he gives her a congratulatory kiss something strange

happens. The sky darkens for a moment as Rita and Julius swap souls.

No one has any idea what just

happened, but on their honeymoon Peter suspects that there’s something wrong

with Rita. Maybe it’s her avoidance of physical intimacy or the odd turn of

phrase (“You’re my puppy puppy.”) or her quick agreement

to quit her job and let him support them or her failure to remember how to make

a Long Island iced tea (and she’s a bartender!). The crucial indicator that

something isn’t right is her ability to finally sleep. Peter finally figures

out what happened between Rita and Julius and the rest of the film plays out

Peter trying to get his wife back in her own body.

Reprising his role from the

Broadway production, Alec Baldwin delivers one of the strongest performances of

his career as a slightly bookish guy who falls in love with a woman that

encourages him to be spontaneous and enjoy being in the moment. The actor is

capable of wonderful little moments, like how he humors Rita’s aunt and uncle

at their wedding reception, while also nailing the big moments as well. This

role requires Baldwin to convey a wide range of emotions over the course of the

film as we see him go from the first blush of romance to almost losing his mind

when he realizes what has happened to Rita. This culminates in the scene where

Peter realizes that the person he married isn’t her anymore. The sadness that

plays over his face when this sinks in is absolutely heartbreaking. After all,

who can he tell? Who would believe him? You really feel for the poor guy.

Meg Ryan is quite good as

Rita as she spends the first half of the film getting Peter (and us) to fall in

love with Rita thanks to that great smile of hers and an independent streak

that makes her a distinctive character instead of a romantic ideal for the male

lead. Ryan is especially good when her body is possessed by Julius’ soul. The

actress subtly changes how she moves and acts. Peter and Rita aren’t the

immature romantic leads that seem to populate so many contemporary romantic

comedies. They are smart, passionate dreamers that care deeply for each other.

I could listen to their conversations forever and secretly hold out hope that

there is a bunch of deleted scenes somewhere with even more conversations

between them. The filmmakers have lured us in so that when the fantastical

twist happens we’ve become emotionally invested in Peter and Rita. We care

about them and want to see them be happy.

The third part of this

equation is Sydney Walker who plays Julius. He does a good job of playing the

old man initially as an impish enigma and then when the swap occurs the actor

has to incorporate many of Rita’s mannerisms in a way that credibly sells the

transformation that takes place. He manages to give the impression that Rita is

in there, inhabiting this body. It is only until the last third of the film

that we get insight into Julius’ motivations and also how Rita was receptive to

the swap.

In 1988, Norman Rene directed

the first stage production of Craig Lucas’ play Prelude to a Kiss in Costa Mesa, California. After extensively

rewriting it (strengthening the storyline and trimming down the number of

characters), the two men took the play to New York City where it debuted on

Off-Broadway, with Alec Baldwin and Mary-Louise Parker in the lead roles, and

then on Broadway with Timothy Hutton replacing Baldwin. The play got rave

reviews and soon Hollywood came calling. Lucas met with 20th Century

Fox in 1989 and the studio secured the film rights for just over a million

dollars in 1990. Two conditions of the sale were that Rene had to direct the

film and Lucas’ screenplay could not be rewritten. Baldwin reprised his role,

but Parker was replaced by the more box office friendly Meg Ryan. Alec Guinness

was originally cast as Julius, but had to leave the production early on when

his wife became ill, and was replaced by theater veteran Sydney Walker.

Prelude to a Kiss received mostly negative reviews from

critics. Roger Ebert gave the film three out of four stars and wrote, “Prelude to a Kiss is the kind of movie

that can inspire long conversations about the only subject really worth talking

about, the Meaning of It All.” In his review for The New York Times, Vincent Canby wrote, “The performances are

colorless … The camera doesn’t reveal characters. The close-ups corner the

actors to expose banalities.” Entertainment

Weekly gave the film a “C-“ rating and Owen Gleiberman wrote, “Prelude to a Kiss is squishy yet blah.

It teaches the characters a lesson they don’t need to learn.” The Los Angeles Times’ Kenneth Turan wrote,

“Fortunately, Baldwin and Ryan form an extremely likable couple, believable

both in their initial unsureness and in how they gradually hook onto each

other’s loose ends.” Finally, in his review for the Washington Post, Desson Howe wrote, “Prelude is at its best when it’s not being a fairy tale. The middle

sags, and the finale is so conveniently beneficial for everyone it ruins any

sense of romantic triumph.”

In these kinds of body swap

movies there is the tendency to exaggerate the change for comic effect, but Prelude to a Kiss avoids the typical

pratfalls and obvious personality clashes for a kind of melancholic tone. The

film consists of two different halves with the first part having a warm and

romantic tone while the second part is tragic and dramatic. It is this tonal

shift that some may find jarring. The soul swapping scene is the most pivotal

point in the film where it risks losing its audience. If you can’t or don’t

want to make the leap in logic that the film does then the rest of it doesn’t

work. Prelude to a Kiss puts an

intriguing spin on the notion of soul mates so prevalent in romantic comedies.

What happens when two people that are meant to be together have their love put

to the test in such an unusual way? Perhaps the answer lies in what Peter says

in voiceover at the beginning of the film when he compares love to riding a

rollercoaster: “Ride at your own risk … They want you to believe that anything

can happen. And they’re right.”

SOURCES

Drake, Sylvie. “Hitting the

Jackpot.” Los Angeles Times. June 5, 1990.

Rea, Steven. “Director’s

Tale: Taking Prelude to a Kiss From

Stage to Screen.” Philadelphia Inquirer. July 12, 1992.