Many people look back at the

1980s through the soft focus lens of nostalgia. They think fondly of John

Hughes’ teen movies or the music of The Police or television shows like Miami Vice or the novels of Stephen

King. The people who grew up in that decade have attempted to pay tribute to

that time in recent years with movies like the remake of It (2017), T.V. shows like Stranger

Things and music by likes of Bruno Mars that invoke the era.

Nostalgia for the ‘80s has

reached its saturation point and people tend to forget that there was a lot of

awful stuff, too, like Reaganomics, the omnipresent threat of nuclear war, the

explosion of Japanese fashion, T.V. shows like Alf, the proliferation of mindless synth pop, and the dominance of

producer-driven Hollywood blockbusters.

One of the films that best

encapsulated the superficial consumerism of the era was Paul Schrader’s American Gigolo (1980). With its icy

Eurotrash score by Giorgo Moroder, its expensive clothes by Giorgio Armani and luxurious

cars like Mercedes and BMW, it established the stylistic template for popular

culture that would be cemented by the equally influential Miami Vice show a few years later for the rest of the decade.

Schrader’s film is often dismissed as a shallow exercise in style while failing

to realize that its style is its substance. It is all surface, reflecting its

materialistic protagonist.

Julian Kay (Richard Gere) is

a high-end male escort specializing in wealthy women. He wears only the best

suits and drives expensive cars. Schrader immediately immerses us in his world

with a montage of him buying suits, driving his Mercedes and dropping off one

of his clients all to the strains of Blondie’s “Call Me” while giving us a tour

of boutique shops, expensive beachfront condos and affluent hotels – the

playground of California’s rich elite.

His world is turned upside

down when he meets a mysterious and lonely woman named Michelle (Lauren

Hutton), the wife of a California state senator. They meet by chance and she

becomes obsessed with him and he finds himself falling in love with her. His

life gets even more complicated when he finds out that a woman he had a kinky

one-off gig with in Palm Springs has been murdered. Julian soon becomes the

prime suspect and begins to lose control of his life that he works so hard to

maintain. He must figure out who set him up and why.

Schrader takes us through

Julian’s process on getting ready for a job. He lays out his suits, opens his

drawer of ties, then dress shirts and so on. It’s a ritual he’s done countless

times and Richard Gere skillfully sells it, showing how all these clothes

inform his character. In this case, the clothes truly make the man. For Julian

it’s all about control. He prides himself in knowing what women want, providing

them with a fantasy that plays into their desires. They both get something out

of their transactions. They feel wanted and desired and he gets paid.

The impossibly handsome Gere

is perfectly cast as the narcissistic Julian. He pays close attention to how he

looks and dresses as they are integral aspects of his job. He has to look good

for his clients. The actor certainly knows how to wear an Armani suit and has

an engaging smile that exudes charm. Julian has his whole act down cold – a

tilt of the head, a sly smile, the way he looks at someone, and the silky

smooth voice are all parts of his arsenal of seductive techniques.

Gere had a terrific run of

films starting in the late 1970s with a small but memorable part in Looking for Mr. Goodbar (1977), Days of Heaven (1978), and then into the

1980s with American Gigolo and Breathless (1983), playing fascinating,

complex characters that weren’t always likable but always interesting to watch

thanks to his incredible charisma.

Lauren Hutton is excellent as

the rather enigmatic woman that takes a shine to Julian. One imagines her being

an unhappy trophy wife who is expected to accompany her husband to all kinds of

political functions with an interested expression plastered on her face. The

actor conveys an impressive vulnerability like when Michelle seeks out Julian

and asks for a date with him. She is frank with what she wants and Hutton is

very good in this scene.

The intimacy between Julian

and Michelle is more than just being physical with each other. It is the conversation

they have after making love for the second time that is interesting as she

tries to get him to reveal personal details. When she asks him where he’s from

he says, “I’m not from anywhere…Anything worth knowing about me, you can learn

by letting me make love to you.” Julian is a blank slate and this allows women

to project their fantasies on him. He can be anything they want, which is why

he’s so good at what he does. He does tell her why he only prefers older women,

which is revealing in and of itself. He cares about pleasuring women. He puts

their needs before his own, often to the detriment of his own pleasure.

It is also interesting how

Schrader objectifies both men and women in American

Gigolo. Initially, as we see Julian ply his trade as it were and it is the

women that are shown naked but when he and Michelle make love the second time

the camera lingers on their respective body parts equally and, in fact,

afterwards we see more of his naked body than hers in one of the earliest

examples of full frontal male nudity in a Hollywood film. As he demonstrated in

this film and a few years later in Breathless,

Gere is a fearless actor very comfortable with his own body.

This translates to the

character as evident in a scene that occurs halfway through the film between

Julian and Detective Sunday (Hector Elizondo) who is investigating the murder

when the latter asks the former, “Doesn’t it ever bother you, Julian? What you

do?” He replies, “Giving pleasure to women? I’m supposed to feel guilty about

that?” When Sunday argues that what he does isn’t legal Julian says, “Legal is

not always right.” He arrogantly says that some people are above the law and at

this point he loses Sunday who sees things in simpler terms.

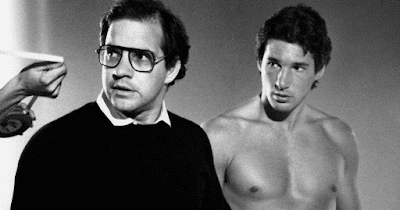

In 1977, Paul

Schrader sold his screenplay for American

Gigolo to Paramount Pictures. The next year John Travolta agreed to star

and the filmmaker felt that the character of Julian Kay was a natural

progression for the actor after his role in Saturday

Night Fever (1977). Schrader had seen Travolta in a photo shoot for Variety where he was unshaven and in a

white suit and felt that he was right for the part. The actor’s participation

set the wheels in motion and the film was given a $10 million budget. The

director auditioned four or five actors for the role of Michelle and liked Mia

Farrow the best but when he tested her with Travolta, “she blew John off the

screen. She made him look like an amateur, like a kid, not like the seducer.”

As a result, he had to go with someone else and cast Lauren Hutton who had

tested well with Travolta. Unfortunately, several things prompted the actor to

drop out of the production: his mother had died, recent movie Moment by Moment (1978) was a commercial

and critical failure, and he was anxious about the homosexual elements in the

script. His departure left Schrader with two days to cast someone else.

After strong

performances in high profile films that weren’t very profitable, Schrader

wanted to cast Richard Gere in American

Gigolo. Then head of Paramount Barry Diller didn’t want him, preferring

Christopher Reeve instead. Schrader didn’t think Reeve was right for the part,

as he was “too all-American, didn’t have that reptile mysteriousness.”

Unbeknownst to the studio, Schrader offered the part to Gere on a Sunday, giving

him only a few hours to decide. Once Gere agreed, Schrader left a note on

Diller’s gate at his home. The executive was understandably upset as the

director wasn’t authorized to do that. Schrader argued that Travolta was better

for Urban Cowboy (1980), which the

studio wanted to make and Diller allowed Gere to be American Gigolo.

Schrader said

of Gere’s commitment to the role as opposed to Travolta: “In one day, Richard

Gere asked all the questions that Travolta hadn’t asked in six months.” Gere

was drawn to the project by Schrader’s approach to how it would be shot, “with

very European techniques – the concept opened up: less a slice-of-life

character study and something much more textured, stylistic.”

When Travolta

dropped out, Schrader was tempted to go back to Farrow, however, he didn’t want

to push his luck with the studio after they let him cast Gere but regrets not

sticking with the actor: “Obviously I did everything I could and Lauren did

everything she could to be as good as she could, but Mia just had stronger

chops.”

When it came to

putting Los Angeles on film, Schrader realized that it had been photographed

countless times and wanted to bring a fresh perspective. He hired production

designer Ferdinando Scarfiotti, who had worked on Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Conformist (1970), Giorgio Armani

for the clothes, and Giorgio Moroder, who had scored Midnight Express (1978), to compose the film’s score. Scarfiotti,

in particular, was an important collaborator as Schrader admired his visual

style and the “idea that you can have a poetry of images rather than a poetry

of words.” He put Scarfiotti in charge of the look of the film, which included

production design, wardrobe, props, and cinematography.

Schrader picked

Moroder to compose the film’s score as he liked the “alienated quality” of his

music and “how propulsive it was, how sexual yet antiseptic. A sound for a new

Los Angeles.” Moroder had originally wanted Steve Nick to sing the film’s theme

song but she turned him down. He sent a demo to Blondie with the music and

lyrics already written. Their album Parallel

Lines was a massive hit but they had not been approached to contribute to a

film. They admired both Moroder and Schrader’s work and agreed to do it. Debbie

Harry didn’t like the lyrics and asked if she could write her own. She saw a

rough cut of the film and the opening scene was in her mind along with

Moroder’s music when the first lines came to her.

Clothes were

also an important aspect of the production. According to Schrader, when it came

to Julian, “the clothes and the character were one and the same. Remember, this

is a guy who has to do a line of coke just so he can get dressed.” Armani had

gotten involved at the suggestion of Travolta’s manager back when the actor was

still attached to the project. The fashion designer was getting ready to go

into an international non-couture line and the timing was right. When Gere came

on board they kept all the clothes and tailored them for the actor.

To prepare for

the role Schrader had Gere study actor Alain Delon in Purple Noon (1960), telling him, “Look at this guy, Alain Delon. He

knows that the moment he enters a room, the room has become a better place.”

According to the actor, the nudity wasn’t in the script, rather “it was just

the natural process of making the movie.” He also didn’t know the character or

his subculture very well: “I wanted to immerse myself in all of that and I had

literally two weeks. So I just dove in.”

In retrospect,

Schrader regrets that the homosexual aspects of the script were toned down to

get studio backing: “At the time, we thought we were being brave, promoting

this androgynous male entitlement. Now I look back, and we were being cowardly.

It should’ve been much more gay. Then again, I probably got it made because

Julian pretends not to be gay.”

At the time, American Gigolo received mostly negative

reviews by several mainstream critics. In his review for The New York Times, Vincent Canby wrote, “Julian Kay is someone of

absolutely no visible charm or interest, and though Mr. Gere is a handsome,

able, low-key actor, he brings no charm or interest to the role. Then, too, the

camera is not kind to him. It's not that he doesn't look fine, but that the

camera seems unable to find any personality, like Dracula, whose image is

unreflected by a mirror.” The Washington

Post’s Gary Arnold wrote, “By the time it sputters to a fade out, Gigolo pays a heavy price for such

sustained pretentiousness in tawdry circumstances. This movie invites a sort of

sarcasm that destroyed Moment By Moment

without ever generating as much naive entertainment value.” Roger Ebert,

however, gave the film three-and-a-half out of four stars and wrote, “The whole

movie has a winning sadness about it; take away the story's sensational aspects

and what you have is a study in loneliness. Richard Gere's performance is

central to that effect, and some of his scenes – reading the morning paper,

rearranging some paintings, selecting a wardrobe – underline the emptiness of

his life.”

If the thriller genre

elements don’t work as well as they should in American Gigolo it’s because the aspects of Julian’s profession and

his developing relationship with Michelle are infinitely more interesting. It

feels like Schrader was still trying things out and would be more successful at

marrying these aspects in the film’s spiritual sequel The Walker (2007) decades later. American Gigolo is a fascinating fusion of the commercial

sensibilities of slick movie producer Jerry Bruckheimer and Schrader’s art

house inclinations (in particular, the films of Robert Bresson), establishing a

stylistic template whose influence would be felt throughout the rest of the

decade. Gone was the gritty, looseness of the 1970s, replaced by a slick sheen

with style and spectacle over character development as epitomized by

Bruckheimer produced blockbusters like Flashdance

(1983) and Top Gun (1986). American Gigolo has aged better than many

of these films thanks to Schrader’s thematic preoccupations, most significantly

a self-destructive protagonist that finds redemption, and Gere’s strong

performance that anchors the film. It may seem like a happy ending inconsistent

with the rest of the film but Julian has survived at a great cost to his

reputation. Everything he is has been torn down and now he must find some way

to rebuild his life.

NOTES

Anolik, Lili.

“Call Me!” Airmail News Weekly. February 8, 2020.

Jones, Chris.

“Richard Gere: On Guard.” BBC News. December 27, 2002.

Krager, Dave.

“Richard Gere on Gere.” Entertainment Weekly. August 31, 2012.

Perry, Kevin

EG. “The Style of American Gigolo.” GQ.

March 2012.

Segell,

Michael. “Richard Gere: Heart-Breaker.” Rolling Stone. March 6, 1980.