Midnight Movies by J. Hoberman and Jonathan Rosenbaum was the first book of film criticism that I

read. They took a look at the rise of cult movies thanks to midnight screenings

all over the United States in the 1960s and 1970s. My parents bought it for me

at a bookstore in Toronto because of my newfound appreciation of David Lynch. Twin Peaks had premiered on television not

long ago and I began seeking out everything he had directed. Midnight Movies devoted an entire

chapter to his early work, in particular Eraserhead

(1977), but it was the afterword where the two critics talked about Twin Peaks in relation to the midnight

movie phenomenon that really stayed with me. Hoberman called the show, “the

ultimate extension of the midnight movie aesthetic and went on to say:

“Twin Peaks is reportedly

extremely popular with college students but what’s more striking is its

figurative and literal domestication of the midnight aesthetic. I think it’s

significant that the network switched the show to Saturday night, which gives

it a kind of generational hook. Where once you might have run off to see Night of the Living Dead at midnight now

you can stay home and watch Twin Peaks.”

After reading that and absorbing his chapters on the works of Alejandro

Jodorowsky and John Waters, I had to read more of Hoberman’s writing. It wasn’t

easy as, at the time, he wrote for the Village

Voice, a newspaper I did not have access to where I lived in Canada.

Eventually, thanks to the Internet, I was able to get access to his film

reviews and read them voraciously.

Hoberman originally wanted to be an avant-garde filmmaker, but found it

to be “really hard and largely thankless.” He had been writing features for

counterculture magazines when Richard Goldstein, arts editor for the Village Voice, invited him to contribute

reviews of avant-garde and cult movies. His debut review was for Eraserhead on October 24, 1977 where he

famously wrote, “Eraserhead’s not a

movie I’d drop acid for, although I would consider it a revolutionary act if

someone dropped a reel of it into the middle of Star Wars.” At the time, Hoberman was the third string writer after

Andrew Sarris and Tom Allen. He remembers that at the time, he wasn’t

“particularly concerned with Hollywood and I didn’t really see myself as a

movie reviewer—more like someone happily toiling in the vineyard of film

culture and getting paid for it.”

When Sarris was seriously ill in 1984, Hoberman temporarily filled in

for him, reviewing his first Hollywood movie, the Clint Eastwood thriller Tightrope (1984). Sarris returned and

Hoberman did such a good job that he was given more mainstream fare to review

and “that’s the point at which I began to hate Steven Spielberg.” He became the

Voice’s senior film critic in 1988

where he worked until 2012.

Hoberman’s approach to film reviewing is “as a form of journalism.

You’re reporting on something, and you get to be much more subjective and

playful than you would be if you were simply reporting a news story, but I

think that you need to provide a certain amount of information and context.” One

of the things the draws me to his writing is a willingness to go against the

grain and defend a film that is universally panned by his counterparts. Case in

point: he was one of the few mainstream critics to “get” Terry Gilliam’s

adaptation of Hunter S. Thompson’s novel, Fear

and Loathing in Las Vegas (1998). While most everyone else was calling it

an incoherent mess he thought otherwise: “At once prestigious literary adaption

and slapstick buddy flick, this is something like Fellini Cheech and Chong—this is a lowbrow art film, an egghead

monster movie, a gross-out trip to the lost continent of Mu, a hilarious paean

to reckless indulgence, and perhaps the most widely released midnight movie

ever made.” In that same vein, Hoberman was one of the few American critics

that defended Richard Kelly’s much maligned sci-fi opus Southland Tales (2006): “Why was the Kelly Code too much to take? Sensory overload is certainly a

factor, but unlike Da Vinci [Code], Southland Tales actually is a visionary film about the end of

times. There hasn’t been anything comparable in American movies since Mulholland Drive.”

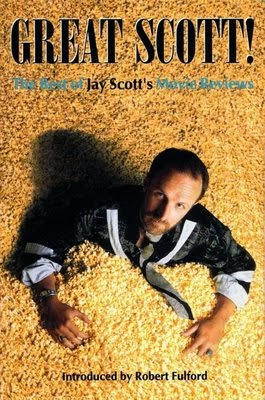

Unlike say, Harlan Ellison or Jay Scott, two film critics who I have

already examined on this blog, Hoberman is a more cerebral writer. To whit, in

his review of Terrence Malick’s The Thin

Red Line (1998): “Terrence Malick’s hugely ambitious, austerely

hallucinated adaptation of James Jones’s 1962 novel – a 500-page account of

combat in Guadalcanal – is a metaphysical platoon movie in which battlefield

confusion is melded with an Emersonian meditation on the nature of nature.”

Another thing I like about Hoberman’s writing style is his ability to come up

with some really brilliant observations about a given film. For example, here’s

a gem from his review of Ghost World (2001):

“It’s smart enough to recognize that, as fleeting as adolescence may be, the

world is haunted by the post-adolescent walking wounded. There’s an admirable

absence of closure. As the title suggests, the movie is a place—or better, a

state of being.”

As is always the case with any critic, I don’t see eye to eye with

Hoberman on everything. His review of Michael Mann’s The Insider (1999) saw him take a few digs at the director’s

signature style:

“Mann rarely misses a chance to savor the brooding dusk from a

skyscraper window, while an ongoing search for the audiovisual equivalent of

purple prose, underscores the high drama with a bizarre mélange of Gregorian

chants and world-music yodeling. At 155 minutes, The Insider may be pumped-up, but it’s rarely boring.”

Hoberman did go on to give Mann’s next film, Ali (2001) a mostly positive review, but I always get the feeling

that he is kind of ambivalent towards Mann’s films, like he wants to like them,

but always finds something wrong with them.

Hoberman tends to play it straight for most of reviews, but every so

often he comes up with a memorable zinger like in his review of Stanley

Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon (1975):

“Back in 1976, Barry Lyndon’s

most problematic aspects was its blatant stunt casting—the equivalent today of

using Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Moss to anchor something like The Charterhouse of Parma. Still young

and beautiful, O’Neal (a TV heartthrob turned superstar with the mega success

of Love Story in 1970) starts out a

ridiculously po-faced dullard and eventually ‘matures’ into a stern-looking

dolt. But Barry Lyndon is a movie

that encourages the long view, and seen from the perspective of a

quarter-century, the actor appears as a blank stand-in for himself, just a

good-looking chess piece for Kubrick to maneuver around the board.”

I find that almost every film reviewer as a critical blindspot – a

filmmaker or genre they just don’t like or don’t get. For Pauline Kael it was

Kubrick, for Hoberman it is the Coen brothers. His main issue with their work

is of the anti-Semitism

he feels is rampant in films like Miller’s

Crossing (1990) and Barton Fink

(1991). This is a rather odd charge considering that Joel and Ethan Coen are in

fact Jewish. In his grudgingly positive review of Inside Llewyn Davis (2013), he lays out his problems with the

Coens’ films:

“Although a robust disdain

for their creatures is a given, it is when the Coens deploy explicitly Jewish

characters that their glee turns hostile. The spectacle of the pathetic

cringing Jew played by John Turturro on his knees and begging for his life in Miller’s Crossing was less antic than

appalling. Turturro starred as another sort of Jew in Barton Fink, which set in 1941, staged a virtual death match

between two then potent stereotypes—the vulgar Hollywood mogul and the arty New

York communist—without any hint that their minstrel show battle royale was

occurring at the acme of worldwide anti-Semitism.”

He then proceeds to

concede that Llewyn Davis is an “almost

affectionate send-up of the early ‘60s Greenwich Village folk scene, is

certainly their warmest film in the 16 years since The Big Lebowski in part because, as in Lebowski, the lead actor—Oscar Isaac—inspires a sympathy beyond the

constraints of his creators’ rote contempt.” In a backhanded complement,

Hoberman finds Davis “something more than a cartoon. So is the movie, which is

predicated on the Coens’ enthusiasm for its music that, particularly as sung by

Isaac, is surprisingly affecting. Malice is tempered by fondness occasionally

verging on admiration.” Wow, it actually sounded like he sort of, kind of liked

it, despite his best efforts not to!

The Village Voice fired Hoberman on January

4, 2012 and he became the next casualty on a long line of prestigious critics

that have been let go from newspapers and magazines. If his firing really

stings it may be that it feels like the end of era. Not to worry, though, he

still continues to write film reviews for the likes of the Los Angeles Times, the New

York Times and The Guardian among

others. He also has his own website where he archives his reviews and promotes

his latest book. Hoberman remains a strong and vital critical voice in a field

that is increasingly dominated by writers that lack the kind of skill and

knowledge that he has accrued over the years.

SOURCES

Goldsmith, Leo. “An Interview with J. Hoberman.” Not Coming to a

Theater Near You. April 22, 2011.

Peranson, Mark. “Film Criticism After Film Criticism: The J. Hoberman

Affair.” Cinemascope. 2012.