The 1980s was quite a

prolific decade for actor Kurt Russell. Sprinkled between the genre classics he

made with director John Carpenter, the actor tried his hand at a wide variety

of roles, from shifty used car salesman in the comedy Used Cars (1980) to a nuclear power plant worker in the docudrama Silkwood (1983) to a police detective in

the neo-noir Tequila Sunrise (1988).

Often forgotten during this busy decade is a nifty little thriller called The Mean Season (1985). Based on the

bestselling 1982 novel In the Heat of the

Summer by John Katzenbach, this well-executed film acts as the cinematic

equivalent of an engrossing page turner.

Set in Miami during the hot,

late summer months, the film opens with an urgent brassy score by the great

Lalo Schifrin that plays over shots of stormy skies juxtaposed with the busy

printing presses of the Miami Journal,

foreshadowing how both will play a prominent role later on. Malcolm Anderson

(Kurt Russell) is a veteran crime reporter that has just come back from hiatus/job

hunting in Colorado. He’s burnt out, lacking both ambition and drive. He wants

a change of pace and threatens to quite… again. But before he can bring it up,

Bill Nolan (Richard Masur), his editor, assigns him to cover the murder of a

young woman that has been shot in the head.

The crime scene sequence speaks

volumes about Malcolm’s character. He’s covered the beat long enough to be on

friendly terms with homicide detective Ray Martinez (Andy Garcia) but not his

partner Phil Wilson (Richard Bradford). He also knows how to get the guy who

found the body to open up and talk then has the decency not to use the man’s

name in the article. Malcolm is also tactful and understanding with the mother

of the murder victim, listening to the woman’s reminisces about her child while

still getting what he needs for the article. This is in contrast to Andy Porter

(Joe Pantoliano), the crime photographer who shadows Malcolm on his assignments

and has no problem taking a picture of the grieving parent during a

particularly vulnerable moment. This scene is important because it establishes

that Malcolm is good at what he does and he is a decent person so we like and

identify with him.

Malcolm finally confronts

Bill about his desire to quit in a scene between veteran character actor

Richard Masur and Russell. Bill tells Malcolm, “You haven’t been at this long

enough to be as burned out as you like to think you are.” Malcolm feels like he’s

seen and done it all but still hasn’t found his Watergate yet – the dream of

all ambitious investigative reporters. Malcolm sums it up best when he tells

Bill, “I don’t want to see my name in the paper next to pictures of dead bodies

anymore.” The editor counters, “Now we’re not the manufacturer, we retail. News

gets made somewhere else, we just sell it.” It’s a nice scene that is

well-played by both actors as their characters touch on the nature of ethics in

reporting the news. How far are they willing to go to get a story that makes

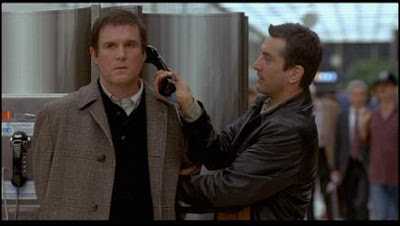

their career? Malcolm is about to find out as he gets a phone call from the man

(Richard Jordan) that killed the teenage girl. He admires Malcolm’s writing and

wants the reporter to be his mouthpiece as he plans to kill again.

Bill is practically

salivating at the possibilities while Malcolm’s ambition kicks in as he

realizes that he’s found his Watergate. However, as the murders continue,

Malcolm finds himself getting more involved in the story until he’s as much a

part of it as the killer, which puts his life and that of his girlfriend

(Mariel Hemingway) in danger.

While the set-up and plot of

The Mean Season are nothing special –

the reporter who gets in way over his head – both are executed well enough that

you don’t mind and this is due in large part to the engaging performances of

the talented cast that do their best to sell the material. Kurt Russell

certainly comes across as a believable newsman. He’s got the lingo down and

seems to know his way around the newsroom and the beat that Malcolm covers. The

actor does a nice job of conveying his character’s transition from someone

reporting on the news to the one making it. He also manages to get a chance to

show off some of his action chops in an exciting bit where Malcolm races across

town to find his girlfriend before the killer does. His frantic, desperate race

is intense because the actor knows how to sell it, running full tilt over

several blocks like a man possessed, and because we know more than he does. We

know just how much danger his girlfriend is in.

Mariel Hemingway is good in

the thankless girlfriend role. She and Russell have good chemistry together.

They make a nice couple together and her character ends up acting as the voice

of reason when Malcolm gets too involved. Hemingway does her best to avoid the

damsel in distress stereotype but it is pretty easy to figure out how it’s all

going to go down. She is part of a solid supporting cast that includes Andy

Garcia as the dedicated cop that cares and Richard Bradford (The Untouchables) as his older, more

experienced partner who thinks that Malcolm is a parasite. The aforementioned

Richard Masur (The Thing) is also

memorable as the opportunistic editor who just cares about selling papers. The

great William Smith (Darker than Amber)

has a memorable bit part as a pivotal witness that helps Malcolm and the cops

track down the killer. He has only one scene with a decent amount of

expositional dialogue to convey but he nails it.

Director Phillip Borsos (The Grey Fox) also does a nice job

orchestrating the cat and mouse game between Malcolm and the killer thanks to

the smartly written screenplay by Leon Piedmont. They manage to hit all the

right notes and fulfill all the right conventions of the thriller genre – the

grudgingly helpful cops, the ambitious reporter, the sociopathic killer, and so

on – and stir it all up. Borsos employs no-nonsense direction like a seasoned

studio pro, which lets the actors do their thing. I also like how he conveys a

sense of place with the sweaty, summer weather, coupled with the impending

hurricane that is almost tangible. It all comes to a head at the exciting and

atmospheric climax when Malcolm confronts the killer in the Everglades.

John Katzenbach was a

veteran crime reporter who based his debut novel In the Heat of the Summer on years of experiences and that of his

colleagues. Producer David Foster, a journalism graduate, had been looking for

a good screenplay about reporters for years. He came across the manuscript for

Katzenbach’s novel and was impressed by it. He met with the author and they

talked about how to accurately convey the life of a newspaper reporter on film.

In April 1984, Borsos and

his crew arrived at the Miami Herald

offices to study a typical day in the newsroom and on that day Christopher

Bernard Wilder, suspected of kidnapping and murdering several young women, shot

himself as the police closed in. The resulting flurry of activity at the Herald helped Borsos create a realistic

newsroom atmosphere in his film. Katzenbach urged Kurt Russell to hang out with

his fellow reporters in preparation for the film. To that end, Russell and Joe

Pantoliano accompanied a reporter and a photographer from the newspaper to the

scene of a grisly double murder in North Miami. Much like in the film, the

actor found cameras were trained on him and later saw footage of himself on the

evening news. In addition, Richard Masur spent days and night son the Herald’s city desk.

Borsos’ previous film The Grey Fox (1982) did not make a

profit and so to pay off his debts he agreed to direct The Mean Season. Unfortunately, he had creative differences with

Foster over the tone of the film. According to Borsos, he wanted the film to

look “somewhat stylized and slightly unreal, more what you would call a 1950’s

film-noir type of picture.” In contrast, Foster wanted a more realistic-looking

film as Borsos said, “Mr. Foster’s vision was more of action-packed thriller

instead of a character-thriller.” It also didn’t help that the director

resented the producer’s constant presence on the set. The newsroom scenes were

actually shot at the Miami Herald

late at night with several staff members used as consultants and extras.

Russell and two fellow actors used three real newsroom desks that were

outfitted with authentic-looking notepads, books, dictionaries and computer

printouts. In addition, Katzenbach was frequently present during filming and

acted as a consultant.

When

The Mean Season was released it

received mixed reviews from critics. In her review for The New York Times, Janet Maslin felt that the film “has a brisk

pace and a lot of momentum. It also has a few more surprises than the material

needed, since Mr. Borsos, who for the most part works in a tense, streamlined

style, likes red herrings.” The Washington

Post’s Rita Kempley wrote, “Overall the film seems a little flat, a little

stale … Director Philip Borsos' style is too dogged to transform Mean

Season into a true thriller, though it serves well as a message

movie on what news is fit to print.” The Globe

and Mail’s Jay Scott felt that The

Mean Season was two films in one: “Still, the two halves add up to a

slickly effective and sometimes thought-provoking whole, a mystery that isn't

quite Klute and that certainly isn't Witness, but that is swifter than

nine-tenths of the contestants in the sparsely run race to entertain adults

without insulting them.” Newsweek’s

Jack Kroll wrote, “This movie has the weather of Body Heat, the moral stance of Absence of Malice and the perverse

plot-angle of Tightrope. It's also

not as good as any of these.” In his review for the Los Angeles Times, Kevin Thomas praised Russell’s performance: “The Mean Season depicts with conviction

and economy how Russell is transformed by covering the serial killings.

Russell, in turn, excels in retaining our sympathy as he becomes caught up in

his assignment.”

The Mean Season is an entertaining film that falters a little bit at the end with a

clichéd “twist” that sees Malcolm suddenly transform into an action hero but

Russell does his best to make it work. At times, it feels like there are two

kinds of films competing – the character-driven thriller that Borsos wanted to

make and the action-packed thrill machine that Foster envisioned. The result is

a sometimes uneven effort. Not every film has to try and reinvent the wheel by

offering some novel take on the genre. There’s something to be said for a

thriller that has nothing more on its mind then to entertain and tell a good

story and that’s something The Mean

Season delivers on both counts.

SOURCES

Gross, Jane. “An Actor

Explores the Fourth Estate.” The New York Times. February 10, 1985.

Johnson, Brian D. “An Eye

for Magic Realism.” Maclean’s. February 25, 1985.

Maslin, Janet. “At the

Movies.” The New York Times. February 1, 1985.