With

the rise of nuclear power in the 1970s fear of its misuse became something of a

mini-fascination in Hollywood with films like The China Syndrome (1979) and Silkwood

(1983) that dealt with the misuse and subsequent cover-up of this energy

source. These were serious-minded message films. Riding on their coattails was Warning Sign (1985), which dealt with a

virus outbreak, the cinematic sibling of the nuclear power disaster film sub-genre,

with notable efforts like The Andromeda

Strain (1971) and The Crazies

(1973). These films were more grounded in the science fiction and horror genres

but the message was still the same – we will pay dearly for messing with things

we don’t fully understand, resulting in our destruction despite even the best

intentions. Director Hal Barwood’s film falls somewhere in-between, with

pretentions towards the hard SF of the former and yet delivering the visceral

thrills of the latter albeit with a solid cast of notable character actors like

Sam Waterston (The Killing Fields),

Kathleen Quinlan (Twilight Zone: The

Movie), and Yaphet Kotto (Alien).

When

a scientist (G.W. Bailey) accidentally steps on a beaker of highly dangerous

chemicals unknowingly dropped by another (Richard Dysart), in a sequence that

strains credibility, an alarm goes off forcing the plant’s head of security

Joanie Morse (Kathleen Quinlan) to lock the place down. Just another day at

BioTek Agronomics, a research center for agricultural innovations but is actually

a secret laboratory that makes bioweapons for the United States government.

Sound familiar? It should. The first few minutes of this film were ripped off

pretty heavily by Resident Evil

(2002).

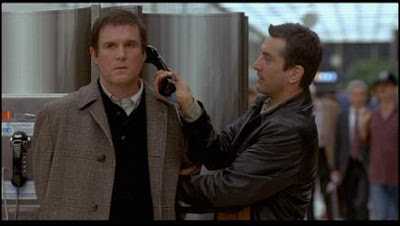

Frustrated

friends and loved ones gather outside the plant trying to find out what

happened, including Sheriff Cal Morse (Sam Waterston), Joanie’s husband. Pretty

soon the government arrives to assess the situation led by a Major Connolly

(Yaphet Kotto) of the U.S. Accident Containment team. Something doesn’t seem

quite right what with Connolly and his men arriving so quickly and Cal figures

out the experimental yeast cover story is a bunch of hokum. So, he tracks down

ex-BioTek employee Dr. Dan Fairchild (Jeffrey DeMunn) who tells him about the

company’s true nature.

Once

BioTek is locked down, Barwood (who also co-wrote the screenplay with Matthew Robbins) does a nice job of ratcheting up the tension as Cal figures out what’s

really going on. The director also doesn’t waste much time introducing the

threat, setting things in motion pretty much right from the get-go and then

letting it all play out, first as a procedural and then, as the situation in

the lab worsens, a horror film with a government away team encountering people

driven into murderous rages by the viral outbreak.

The

always watchable Jeffrey DeMunn (The Blob)

is excellent as the jaded ex-employee who begrudgingly helps Cal. Along with

the local lawman, he acts as a voice of reason and the only hope the former has

of being reunited with his wife Joanie. He also gets to deliver a lot of

expositional dialogue, filling us and Cal in on how the virus works. DeMunn is

such good actor that he can make this dialogue so interesting that we want to

know more. A pre-Law & Order Sam

Waterston is also believably convincing as the concerned husband who will do

anything to get his wife out of the contaminated facility despite his

near-paralyzing fear of germs (a tacked on bit of business that is never really

developed). The actor brings his customary gravitas to the role, which helps

cut down the cringe-inducing bits of dialogue, like at one point saying he

feels like Dirty Harry. Fortunately, he and DeMunn do the best they can and

play well off each other, Waterston the stand-up lawman and DeMunn the burnout

scientist. They make an even better team after breaking into the facility, looking

for Quinlan’s beleaguered security chief.

Kathleen

Quinlan gives a solid performance as the resourceful security chief faced with

the frightening realization that she is trapped in a sealed off facility with

co-workers driven crazy by chemicals. She is smart, following protocol to lock

things down, and then tough as she bravely navigates the various dangers

brought on by the outbreak. She and Waterston have nice chemistry together,

even when they are reduced to talking to each other via walkie talkies. They

make for believable couple that you want to see reunited. It is also

interesting to see these two actors cast against type in action-oriented roles.

Hal

Barwood got his start as a screenwriter, often working with Matthew Robbins on

films like Corvette Summer (1978) and

Dragonslayer (1981), but he always

wanted to direct: “In writing, you’re always watching directors ruin your stuff … There’s a tendency to

want to get your hands on the controls and do it yourself.” After his

screenplay for MacArthur (1977) was

butchered (according to Barwood), he and Robbins decided to write and direct

their own material. The inspiration for Warning

Sign came from history. While researching genetic engineering, they

discovered the Borna virus, which occurred in Germany during World War I. It

was very rare and only affected horses and other animals, driving them crazy

until attacked each other. The other historical factoid they came across was the

1976 outbreak of Legionnaire’s disease in Philadelphia. Robbins found the

notion of a “new and hitherto unknown disease infecting people,” fascinating.

He

and Robbins did a fair amount of research on viral outbreaks and uncovered

little-known germ warfare experiments conducted by the United States in the

1950s, including an incident where the government dispersed a disease by plane

off the coast of San Francisco. Interestingly, Barwood didn’t draw upon other

viral outbreak films like The Andromeda

Strain (1971) for inspiration but rather Night of the Living Dead (1968) because it had the “sensibility of

horror happening in the midst of everyday events.” For some time, he planned on

Warning Sign to be his directorial

debut, done quickly and on a modest $7 million budget originally from the Ladd

Company in early 1982 but at some point moving the project to 20th

Century Fox. To help temper his inexperience as a director, Barwood cast actors

who were skilled and experienced enough that he wouldn’t have to worry about

getting good performances out of them.

Warning Sign received mostly mixed to negative

reviews from critics. In his review for The

New York Times, Jon Pareles wrote, “Warning Sign is

unlikely to start a national debate on biological warfare; it does, however,

while away the minutes kinetically.” The Globe

and Mail’s Salem Alaton said of Barwood’s approach: “He's got a didactic

melodrama full of hackneyed messages when he could have made a lively comedy

called Night of the Living Post-Graduates.”

In his review for the Los Angeles Times,

Kevin Thomas praised the performances of DeMunn, Quinlan and Waterston but felt

that “for all its energy and considerable technical finesse, it's never fully

engaging either.”

Barwood

does a nice job of creating a real sense of dread and danger as he utilizes

tried and true horror conventions, like fear of the unknown to great effect. He

also adopts a siege mentality a la George Romero, making Warning Sign a kind of retroactive prequel to The Crazies as one imagines BioTek being the company that creates

the bioweapon unleashed on the unsuspecting townsfolk in Romero’s film. It’s

just a shame that time and time again Barwood’s film is let down by its

pedestrian script. It is also kind of alarming just how much Resident Evil cribs from Warning Sign only with a bigger budget

and an emphasis on action and spectacle. Because Barwood’s film isn’t that well

known, disappearing soon after it was released, the connections between the two

films are rarely made. For all of its clunky dialogue, Warning Sign is still enjoyable thanks to the performances of

DeMunn, Quinlan and Waterston who manage to rise above the material.

SOURCES

Lowry,

Brian. “On the set of Warning Sign.” Starlog.

September 1985. Pg. 64-66.

Lowry,

Brian. “Hal Barwood: The Shock of Directing.” Starlog. December 1985.