In the 1990s it seemed like Jean-Claude Van Damme was the appointed gatekeeper in Hollywood that Hong Kong action filmmakers had to get past to work in America. Between 1993 and 1997 he starred in the American debuts of John Woo, Ringo Lam and Tsui Hark to varying degrees of success. Despite being marred with production challenges and post-production clashes with his leading man, Woo’s movie, Hard Target (1993), is the most interesting effort of the three filmmakers even in its compromised final form. It stands as a cautionary tale rife with ignorant studio executives and an egotistical movie star.

In New Orleans, rich men pay $500,000 to hunt and kill defenseless combat veterans down on their luck for sport. These hunts are facilitated by Emil Fouchon (Lance Henriksen) and his right-hand man Pik van Cleef (Arnold Vosloo). Natasha Bender (Yancy Butler) comes to town looking for her estranged father that she hasn’t seen since she was seven-years-old. Unfortunately, he was the man brutally murdered in the movie’s opening sequence.

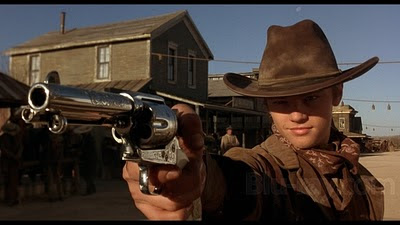

She soon crosses paths with mysterious drifter Chance Boudreaux (Van Damme), an unemployed Cajun and ex-United States Marine, when he rescues her from four random thugs accosting her in an impressively staged sequence that shows off his fighting skills. When going through official channels proves to be futile (because her father was homeless), Nat hires Chance to find her father. Their investigation uncovers Fouchon’s business and they soon find themselves being hunted by him and his rich clients.

Along with Terry Gilliam’s The Fisher King (1991), Hard Target is a rare Hollywood movie to feature the plight of the homeless so prominently. Nat and Chance’s investigation takes them to through homeless population in the city and Woo’s camera lingers on their horrible living conditions. He also shows some of the jobs they must do to survive. The movie also gives noteworthy screen-time to blue collar workers in a scene where Chance tries to sign up for a merchant marine job only to find that he has outstanding union dues, which feels like Woo’s sly nod to On the Waterfront (1954) only Van Damme is no Marlon Brando. It is also sympathetic to war veterans with the targets that Fouchon picks being ex-military men who we are clearly meant to side with, including Chance.

Sporting an unfortunate mullet, Van Damme fumbles his way through the screenplay and Woo wisely tries to limit his dialogue, understanding that his leading man is much more comfortable kicking the crap out of people. He can’t even say a one-liner zinger very well. Look at how he tries to do it compared to how Arnold Vosloo does in several scenes. Obviously, he’s a better actor than Van Damme. Woo does what he can to try and impart a modicum of depth by filming Van Damme in slow motion or having lingering shots of Chance thinking, trying to figure things out.

Lance Henriksen and Woo give the character of Fouchon a bit of depth where the script is unable to by doing it visually, like in an amusing scene that starts with the baddie dressed in white playing a classical piece of music on a piano in his mansion. Is this to show that he’s not just a sadistic businessman but also a frustrated artist? Who knows? The actor is clearly having fun with the role, relishing the part of an evil capitalist that literally preys on people. Fouchon seems to honestly believe the B.S. he pitches to his clients, telling one, “It has always been the privilege of the few to hunt the many…Men who kill for the government do it with impunity. Now all we do is offer the same opportunity for private citizens.” Henriksen fleshes out his character with odd little affectations, like how Fouchon stops to fix his hair in a mirror right after Pik kills one of their flunkies, or how he carries a gun that only fires one bullet at a time (albeit a big bullet), which is extremely impractical but does illustrate the character’s ego.

Vosloo matches him beat for beat as his cultured enforcer. Like Henriksen, he has a great voice – a smooth South African accent that gives his baddie an exotic vibe. They play a sadistic tag team that don’t take too kindly when their flunkies make mistakes as evident in a scene where Fouchon and Pik discipline the man that picks their targets with a large pair of scissors. After clipping off part of the man’s ear, Pik delivers a parting shot with deadpan perfection, “Randal, I come back here – I cut me a steak.” He jams the scissors into the wall for dramatic effect that is pure Woo. The two actors play well off each other with Henriksen playing a more emotional character prone to angry outbursts while Pik is cold and emotionless. There’s a reason why these two characters get the bulk of the movie’s memorable dialogue.

Woo puts his distinctive stylistic stamp on movie right away as he employs slow motion techniques during the sequence where an unfortunate homeless man is hunted by men clad all in black riding on motorcycles (a visual nod to Woo’s previous film Hard Boiled). He also utilizes freeze frames and an editing style that shows the same action from several different angles reminiscent of his work in The Killer (1989) and Hard Boiled (1992).

No amount of studio meddling can completely neuter Woo’s full-blooded style as he inserts some of his trademark visual motifs, like white doves flying in slow motion near the movie’s hero, in this case a scene where Chance connects the dots in Nat’s father’s case. For the last 30 minutes, Woo ups the carnage to ridiculous levels as Chance forces Fouchon and his men to hunt him on his turf in a fantastically choreographed series of action set pieces in a warehouse storing old Mardi Gras floats. Woo pulls out all the stops, employing his trademark action flourishes – someone firing two guns at the same time, two men shooting at each other at close range, and other inspired bits, like a great shot of Chance kicking a can of gasoline in the air and shooting it with a shotgun, which sets it and his assailant on fire.

Even Woo’s stylishly framed shots can’t distract from ridiculous moments like when Chance punches a snake in the head to subdue it and then bites off its tail. The film’s intentional comic relief is provided late on by the welcome appearance of Wilford Brimley as Chance’s moonshine-making uncle who lives deep in the bayou and sports an outrageously scenery-chewing Cajun accent. Brimley appears to be fully aware of the silly action movie he’s in and embraces it wholeheartedly.

While working on Hard Boiled, Woo was worried about Hong Kong’s impending transfer to mainland China and the restrictions that would inevitably be put on his work by the new regime. He had always wanted to make movies in Tinseltown and, as luck would have it, he received a phone call from executive vice-president of production at 20th Century Fox’s Tom Jacobson who wanted to produce one of his films, giving him several screenplays to read. Woo also got a call from Oliver Stone who wanted to produce a modern kung-fu movie set in South Asia and Los Angeles. He gave Woo a script, which he liked but the project fell through.

After completing Hard Boiled, Woo’s business partner Terence Chang introduced him to Universal Pictures producer Jim Jacks who, at the time, had a project called Hard Target with action star Jean-Claude Van Damme already in place with a screenplay by written by former Navy SEAL Chuck Pfarrer. When developing the script, Jacks worked with Pfarrer and they had discussed both Cornel Wilde’s The Naked Prey (1965) and the 1932 adaptation of The Most Dangerous Game as templates. The first one didn’t work and they decided to go with the second, setting the story in New Orleans to explain Van Damme’s accent. The producer was looking for a director after Andrew Davis turned it down. Woo was given the script and liked it but needed convincing. Jacks, Pfarrer, and Van Damme flew to Hong Kong to meet with the filmmaker to talk about the project, which he agreed to do.

The studio needed convincing to hire a filmmaker known for “over-the-top, melodramatic action movies,” according to Jacks. The studio didn’t know any of Woo’s films and it wasn’t until studio chairman Tom Pollock said, “Well, he certainly can direct an action scene. So if Jean-Claude will approve him, I’ll do it with him.”

When Woo arrived for work he experienced the culture shock of being inundated with a seemingly endless supply of meetings with executives and bureaucratic red tape he had deal with before shooting began. He was also surprised that movie stars had so much power: “They had final cut approval, final draft approval, lots of final approvals! And I was so shocked because in Hong Kong the director is everything. The director has so much freedom to do whatever he wants!”

Despite a language barrier, Woo worked well with most of the cast, giving them artistic license as Arnold Vosloo remembered, the director encouraged them to “Go for it, you guys [Arnold and Lance] go off and find out who these guys are. He allowed us that freedom and luxury of doing that.” Woo worked around the language barrier early on by listening more and speaking less, conveying his points by facial expressions, gestures or a few words.

Woo also got on very well with Lance Henriksen right from the start: “When I met him, I unconsciously shook his hand bowed. It was one of those moments of absolute respect for each other,” the actor said. In return, Woo let him pick out his character’s wardrobe and allowed him to ad-lib some of his dialogue, a few lines actually made it into the final cut.

The one cast member Woo did have difficulty with was Van Damme due to his own limited ability with English, his ego and his role as one of the film’s producers. The movie star insisted that one camera be dedicated to close-ups of his oiled biceps. Woo was always waiting for Van Damme who was on his phone making deals with other studios or working on other projects while everyone else was setting up a shot. Vosloo also backs up Woo’s account of Van Damme’s behavior on set: “If he had somebody that was more willing to be a player as opposed to a star, it would have been a far better film – but Jean-Claude really hurt John.” Vosloo claimed that Van Damme would show up to the set after Woo had already set up shots and questioned his choices then told him to do it another way.

In addition to Van Damme lording his producer status over Woo, the studio was concerned that the filmmaker wouldn’t be able to handle an American film crew so they hired Sam Raimi to shadow him on the set and take over if he got in trouble. This backfired when Raimi became one of Woo’s most ardent supporters, arguing with executives over his creative freedom during post-production when Van Damme wanted to do his own cut of the film with the help of the chief editor from the studio behind Woo’s back until Raimi stepped in:

“Of course, I was so upset, you know. ‘It's not right! This is my movie, I should do my own cut!’ And Sam wasn't happy as well, so he arranged a big meeting. He got together all the producers and the editor and he was screaming in the meeting! ‘This is a John Woo movie! Let John do his work!’ And he made everybody back off, and I was so grateful.”

Unfortunately, Raimi could only do so much and in addition to running into studio interference, Woo’s cut of the film ran afoul of the MPAA who made him cut it down from an X rating for violence to a more marketable R rating. The critical reception wasn’t much better. In her review for The New York Times, Janet Maslin wrote, "Hard Target does what it can to present Mr. Van Damme in a bold new light. Curiously, the film's neo-Peckinpah taste for slow motion gives Mr. Van Damme's stunts a balletic quality that diminishes their spontaneity." The Washington Post's Desson Howe wrote, "Essentially, Hard Target is a risk-averse Van Damme vehicle, steered by many hands, and set on tracks leading directly to the delivery entrances of the country's video stores. Woo isn't the driver by any means. He's just a VIP passenger along for the ride."

In his review for the Los Angeles Times, Kenneth Turan wrote, "Woo’s particular brand of idiosyncratic sentimentality, however, is largely absent (a victim, apparently, of the testing process), as is Chow Yun-fat, the star of all of Woo’s most recent films and the director’s alter ego. Van Damme, the erstwhile 'Muscles From Brussles,' turns out to be an insufficient replacement, woodenly stymieing all of Woo’s persistent attempts to mythologize him via careful use of slow-motion photography.” Finally, Entertainment Weekly gave the movie a "B+" rating and Owen Gleiberman wrote, "By the time Hard Target reaches its amazing climax, set in a warehouse stocked with surreal Mardi Gras floats, the film has become an incendiary action orgy, as joyously excessive as the grand finale in a fireworks show. Woo puts the thrill back into getting blown away."

Woo fared better with his next movie Broken Arrow (1996), which still diluted his style and thematic preoccupations but it did bring him together with John Travolta, hot off Pulp Fiction (1994), and who would become an important collaborator on his most creatively successful Hollywood film, Face/Off (1997), which allowed the filmmaker to finally cut loose stylistically and thematically, having learned how things worked within the studio system.

SOURCES

Keeley, Pete. “Hard Target at 25: John Woo on Fighting for Respect.” The Hollywood Reporter. August 24, 2018.

Hall, Kenneth E. John Woo: The Films. McFarland & Co. 2005.