In the Search of the Last Action Heroes (2019) is a

documentary that is both a loving tribute to 1980s action cinema and a lament

of the decline of R-rated action movies starring the likes of Arnold

Schwarzenegger, Sylvester Stallone and Jean-Claude Van Damme. Remember when

Steven Seagal was a lean, mean fighting machine, kicking ass in mainstream

Hollywood studio movies? He emerged from seemingly nowhere fully formed,

complete with model-starlet wife Kelly Le Brock and a headline-grabbing

backstory that involved teaching martial arts in Japan and being recruited by

the CIA to participate in top secret missions, all thanks to a boost from

legendary power broker cum agent Michael Ovitz who helped engineer his

semi-autobiographical Hollywood debut with Above

the Law (1988).

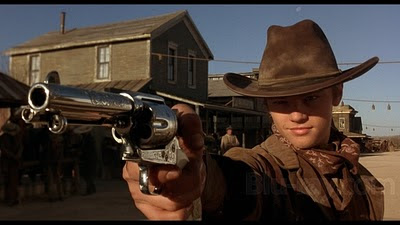

Back then Seagal was a breath of fresh air in action cinema. He wasn’t a muscle-bound one-man army like Schwarzenegger and Stallone, but a normal-looking guy that was a master of the martial art Aikido. There was a no-nonsense vibe to his persona that cut against the grain of the wisecracking tough guys that were dominating the box office at the time. All he needed was the right vehicle to showcase his talents and Above the Law was that movie, more than doubling its budget at the box office and launching Seagal’s movie career.

Davis handles the action like a pro, mixing it up so we don’t get an endless series of scenes of Seagal beating up guys. We see him using his gun and even hanging onto the roof of a car trying to bust some scumbags. It’s not The French Connection (1971) but it is exciting. There’s also a fantastic foot chase where we see Seagal running and not the usual Hollywood bullshit but him flat-out sprinting in smoothly choreographed tracking shots.

Seagal acquits himself just fine in Above the Law and what he lacks in acting chops he more than makes up for in intensity and confidence in his abilities. It helps that Davis surrounds him with the likes of Pam Grier and a bevy of Chicago character actors such as Ron Dean (The Fugitive), Jack Wallace (Homicide), and Ralph Foody (Home Alone) – most of whom appeared in the director’s previous Chicago-based actioner Code of Silence (1985). They provide local color and help give a real sense of place.

Above the Law sets up CIA drug traffickers as the bad guys led by the always reliable Henry Silva who bookends the movie as a nasty piece of work that specializes in torture. With his smooth voice and icy intensity, he makes for a chilling villain that enjoys his work a little too much thanks to the actor’s deliciously evil performance. His imposing presence makes Zagon a formidable antagonist for Seagal.

When he was a teenager, Steven Seagal moved to Japan in 1968, studied and became an expert in the martial arts known as Aikido, so much so that he was the only Westerner to operate his own dojo there. He claimed that several CIA agents operating in the country became students at his dojo. It has been said that Seagal was subsequently recruited by the agency but in interviews he refused to cite specific missions only saying, “You can say that I lived in Asia for a long time and in Japan I became close to several CIA agents. And you could say that I became an adviser to several CIA agents in the field and, through my friends in the CIA, met many powerful people and did special works and special favors.”

It is telling, however, that at the time of filming director Andrew Davis said, “What we’re really doing here with Steven is making a documentary.” Furthermore, Seagal said, “The whole motivation behind me doing this film was my trying to make up for all the things I’ve seen--and done. I’m tired of seeing us try to destabilize governments, prop up dictators and get involved with drug smugglers and crooks.” We will probably never know if Seagal worked for the CIA but it made for good hype that helped garner interest in the movie.

Michael Ovitz, then head of CAA, one of the most powerful talent agencies in Hollywood, was a martial arts aficionado that reportedly studied with Seagal at his West Hollywood based Aikido Ten Shin Dojo. They became friendly and Ovitz felt that Seagal had the raw materials to become a movie star. Then Warner Brothers president Terry Semel remembers Ovitz being Seagal’s biggest fan: “He went far beyond the role of just being Steven’s agent. In fact, with the type of superstar client list Michael has, you wouldn’t normally see him work so closely with a first-time actor.”

Ovitz kept insisting to Semel that Seagal had potential to be a movie star. When it came to the studio courting Seagal, he claimed that they felt Clint Eastwood was aging out of the action genre and told the martial artist, “We’d like to see you take his place. We think you can be the next Eastwood.” They gave him a several scripts, told him to pick one and they’d make it. Not surprisingly, Semel’s account differs: “I don’t think it was a matter of anyone replacing Clint. He’s gone far beyond being just an action star.”

Before Warner Brothers greenlit the movie, they wanted to see a demonstration of Seagal’s martial arts prowess. Needless to say, he didn’t disappoint, putting on quite a show with his assistants: “The demonstration was quite miraculous. With just a toss of his hand, Steven would send the other guy flying. I’m no martial-arts expert, but he had the ability to knock these guys up in the air so effortlessly--well, it was pretty astounding,” said Semel. It was enough for the studio to bankroll a $50,000 screen test with Davis shooting several scenes from the screenplay.

The nine-week shoot was not without incident. Seagal broke his nose in a scene where Henry Silva accidentally punched him. Seagal went to the hospital, was treated and came back to work. Afterwards, he didn’t blame Silva: “My biggest nightmare is having someone like Henry--whose eyes are bad and isn’t trained in stunts--to be swinging at me. I should have my own people in here, doing the stunts.” In addition, Seagal was not used to the slow pace of the filmmaking process with technical delays and having to compromise in action sequences: “Sometimes I’ll tell Andy (Davis) that a scene isn’t going to work. And sure enough, when we see the dailies, it doesn’t look right. I just feel that I’m being shortchanged, that I’m not getting to show enough great martial-arts action.” The filmmakers were also under the gun to finish before a threatened Director’s Guild strike, which only added to the pressure.

Not surprisingly, Above the Law received mostly negative reviews with the exception of Roger Ebert who gave it three out of four stars and said of Seagal, "He does have a strong and particular screen presence. It is obvious he is doing a lot of his own stunts, and some of the fight sequences are impressive and apparently unfaked. He isn’t just a hunk, either." In his review for The New York Times, Vincent Canby wrote that the movie, "may well rank among the top three or four goofiest bad movies of 1988. The film...is the year's first left-wing right-wing-movie. It's an action melodrama that expresses the sentiments of the lunatic fringe at the political center." The Washington Post's Hal Hinson wrote, "Above the Law, which offers Steven Seagal to the world as a new urban action hero, is woefully short on originality, intelligibility and anything resembling taste. But none of this comes as a surprise. What is surprising is how little invention or energy there is in the movie's action sequences."

In his review for the Los Angeles Times, Michael Wilmington wrote, "Starting in the semi-realistic framework of the ‘70s cop movies, it veers off into ‘80s action movie cloud-cuckoo land: the paranoid one-against-a-hundred clichés of the average Schwarzenegger-Stallone heavy-pectoral snow job." Finally, the Chicago Tribune's Dave Kehr wrote, "The action sequences are sleek and strong enough, but the story that chains them together is too ambitious for its own good. Upstanding liberals both, Davis and Seagal seem distinctly uncomfortable working in a genre as inherently right-wing as the cop thriller, and they`ve tried to salve their consciences by introducing some heavily 'progressive' elements."

The commercial success of Above the Law launched Seagal into the action movie star pantheon, kicking off a fantastic run of movies in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s. He was paired with solid directors like Davis and John Flynn (Out for Justice), worked with wonderful character actors like Chelcie Ross (Major League) and William Forsythe (Raising Arizona), and worked with decent budgets. Seagal, however, began to believe his own hype and his ego took over. He began making odd choices in movies, exerting too much control, like starring, producing and directing On Deadly Ground (1994), and the quality suffered. Hollywood stopped bankrolling his movies and he became a cautionary tale, a pop culture punchline and downright toxic when allegations of his sordid personal life eclipsed his professional one.

Above the Law has a coherent, well-written story wedged between action sequences that deals with political assassinations, international drug cartels and drug money-funded wars – ambitious stuff for an action movie. It’s good to see that the filmmakers cared about such things instead of it being an afterthought to be stitched on. Davis doesn’t try to re-invent the cop movie genre and he doesn’t need to – instead, he expertly fulfills many of its conventions and in entertaining fashion. The movie acts as a showcase for a talented action star and is a fantastic snapshot of an emerging movie star with a promising career ahead of him.

Goldstein, Patrick. “Steven Seagal Gets a Shot at Stardom.” Los Angeles Times. February 14, 1988