Without a

doubt, Timothy Agoglia Carey is one of the most eccentric character actors in

American cinema. This is a man that was fired from Stanley Kubrick’s Paths of Glory (1957) for faking his own

kidnapping. One only must see his scene-stealing performances in the likes of

the aforementioned film where he breaks down and cries hysterically before a

firing squad or in The Killing (1956)

where he speaks most of his dialogue while flashing his clenched teeth to

witness the wonderful off-kilter choices he made that enhanced the films he was

in. Unfortunately, he rarely got to headline a film with The World’s Greatest Sinner (1962), which he starred in, wrote,

directed and produced, being one of the rare exceptions. Freed from the

constraints of the Hollywood studio system, he created a crudely made, yet

fascinating look at the cult of personality.

The film

begins, appropriately, in bizarre fashion with the title song playing over a

black screen and the sound of an explosion segues into the opening credits with

classical music playing over the soundtrack inducing wicked tonal whiplash. In a

gleefully audacious move, the story is narrated by none other than God (and

then, bafflingly, abandons it for the rest of the movie) who introduces us to

Clarence Hilliard (Carey) by describing him as “just like any other male the

only difference is he wants to be God. And that’s coming right out of the horse’s

mouth.”

He lives

in domestic bliss with his wife Edna (Betty Rowland) and his two children, working

as the head of the department of an insurance company. One day, he decides to

give everyone the day off which doesn’t sit too well with his boss (Victor

Floming). It doesn’t help that Clarence has also been telling potential clients

not to get insurance, telling one person not get a funeral policy because, “When

you die, your body starts to stink.” Not surprisingly, he gets fired from his

job, comes home and tells his wife that he wants to write a book and get into

politics (?!).

While he earnestly tells her about his aspirations she falls asleep so he tells his pet horse Rex about a dream he had: “I’m gonna make people live long. I wanna put something into life. I wanna make life be eternal.” These are the seeds for a cult that he plans to start but how will he get people to follow him? One night, he goes to a rock ‘n’ roll concert and observes teenage girls screaming in excitement at and worshipping the lead singer. The next day, Clarence hits the streets, literally, preaching eternal life to anyone who will listen. He wants to make people super human beings, promising, “age won’t exist anymore.”

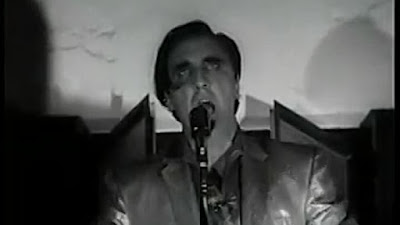

Clarence

transforms himself into a rock ‘n’ roll preacher in a show-stopping sequence

that evokes Elvis Presley and James Brown in raw energy and showmanship as he

sweats, yells and dances with wild abandon. It is a truly astonishing

performance to behold. He eventually changes his name to God Hilliard and

becomes drunk on power, alienating his earlier followers and even his family.

He meets a shady, political fixer whose credentials are that he worked for one

of the leading political parties but fell out of favor thanks to “a few jealous

underlings” and “got into a few difficulties.” He dazzles Clarence with

political doublespeak and tells him, “If you can stir the people’s emotions,

you can win.” The first thing he does is get Clarence to drop the rock ‘n’ roll

preacher shtick, which he agrees to do by dramatically smashing his guitar over

a desk.

He is

soon running for President of the United States on his eternal life platform.

Eventually, his rhetoric changes to that of a fanatical dictator: “We must gird

ourselves with an armor of inspiration. We’ll reach them in the big cities! In

the small towns! And the crossroads! We’ll weed them out! Any place where there’s

people, we’ll get our message to them!” Carey lays on the fascist imagery as Clarence’s

followers wear armbands of their party and have their own book documenting

Clarence’s manifesto. Soon, he is speaking at larger and larger rallies until

he has a crisis of confidence and of faith at the film’s climax.

The making of The World’s Greatest Sinner was almost as wild and unpredictable as the film itself with the inspiration coming from Carey’s desire to shake things up in Hollywood: “I was tired of seeing movies that were supposedly controversial. So I wanted to do something that was really controversial.” He began filming in 1956 in El Monte, California, where he lived, at his home and on the city streets, using locals as extras. This continued sporadically until 1961 on a budget of $100,000 under its original title, Frenzy. While making The Second Time Around (1961), Carey was approached by a young musician by the name of Frank Zappa who complimented his acting. Carey told him, “We have no music for The World’s Greatest Sinner. If you can supply the orchestra and a place to tape it, you have the job.” The aspiring musician composed the score and then went on The Steve Allen Show and said it was “the world’s worst film and all the actors were from skid row.”

Filmmaker

Dennis Ray Steckler (Incredibly Strange

Creatures) also got his start on the film. After several cameramen had been

fired during filming, Carey brought Steckler out to Long Beach to shoot scenes

of extras watching Carey on stage and then rioting. Steckler later claimed that

at while was in a closet loading film, Carey threw a boa constrictor in with

him. To top it all off, at the film’s premiere, Carey fired a .38 pistol above

the heads of the audience, causing a riot.

The World’s Greatest Sinner warns about the

dangers of demagogues like Clarence by showing how he whips a large crowd into

a blind frenzy showing how they are swept up by his fiery rhetoric. Carey shows

how this can be dangerous as his followers riot, destroying property in his

name with the camera lingering on a mob of people trashing and turning over a

car. He has affairs with multiple women, including a 14-year-old girl. This

kind of behavior and these kinds of tactics anticipate T.V. evangelists that

became popular in the 1980s and in recent years people with little to no

political experience or knowledge getting into office based mostly on their

cult of personality and ability to appeal to people’s basest instincts.

What is so incredibly inspiring about The World’s Greatest Sinner is how Carey commits 100% to the wonderfully insane narrative. Imagine if Brad Garrett and Nicolas Cage had a baby and you get Carey. He has the former’s hulking frame with the latter’s bedroom eyes and fearlessness as an actor, not afraid to look ridiculous all in the name of art. The film is shot and edited roughly, almost haphazardly in a non-traditional way with awkward transitions and shifts in tone that is also part of its charm. Carey is not only flaunting Hollywood conventions he is throwing out the rule book as he makes all kinds of odd choices throughout the film, like when Clarence’s boss takes him to his office to reprimand him and it plays over a cacophony of noises so that we can’t hear the dialogue. The screenplay, at times, is truly inspired with such blatantly provocative lines, such as “The biggest liar of mankind is Christ!” This is truly an auteur film – Carey’s magnum opus, a weird and wild film he was somehow able to be unleashed on the world seemingly through sheer force of Carey’s will.

SOURCES

McAbee,

Sam. “Carey: Saint of the Underground.” Cashiers du Cinemart. #12. 2001.

Murphy,

Mike. “Timothy Carey.” Psychotronic. #6. 1990.

While he earnestly tells her about his aspirations she falls asleep so he tells his pet horse Rex about a dream he had: “I’m gonna make people live long. I wanna put something into life. I wanna make life be eternal.” These are the seeds for a cult that he plans to start but how will he get people to follow him? One night, he goes to a rock ‘n’ roll concert and observes teenage girls screaming in excitement at and worshipping the lead singer. The next day, Clarence hits the streets, literally, preaching eternal life to anyone who will listen. He wants to make people super human beings, promising, “age won’t exist anymore.”

The making of The World’s Greatest Sinner was almost as wild and unpredictable as the film itself with the inspiration coming from Carey’s desire to shake things up in Hollywood: “I was tired of seeing movies that were supposedly controversial. So I wanted to do something that was really controversial.” He began filming in 1956 in El Monte, California, where he lived, at his home and on the city streets, using locals as extras. This continued sporadically until 1961 on a budget of $100,000 under its original title, Frenzy. While making The Second Time Around (1961), Carey was approached by a young musician by the name of Frank Zappa who complimented his acting. Carey told him, “We have no music for The World’s Greatest Sinner. If you can supply the orchestra and a place to tape it, you have the job.” The aspiring musician composed the score and then went on The Steve Allen Show and said it was “the world’s worst film and all the actors were from skid row.”

What is so incredibly inspiring about The World’s Greatest Sinner is how Carey commits 100% to the wonderfully insane narrative. Imagine if Brad Garrett and Nicolas Cage had a baby and you get Carey. He has the former’s hulking frame with the latter’s bedroom eyes and fearlessness as an actor, not afraid to look ridiculous all in the name of art. The film is shot and edited roughly, almost haphazardly in a non-traditional way with awkward transitions and shifts in tone that is also part of its charm. Carey is not only flaunting Hollywood conventions he is throwing out the rule book as he makes all kinds of odd choices throughout the film, like when Clarence’s boss takes him to his office to reprimand him and it plays over a cacophony of noises so that we can’t hear the dialogue. The screenplay, at times, is truly inspired with such blatantly provocative lines, such as “The biggest liar of mankind is Christ!” This is truly an auteur film – Carey’s magnum opus, a weird and wild film he was somehow able to be unleashed on the world seemingly through sheer force of Carey’s will.