Thanks to Michael Bay, most horror film remakes are regarded with scorn and skepticism. His production company has managed to crank out a string of unimaginative, slick rehashes often made by music video directors and starring young, unremarkable actors from television. So, there weren’t many expectations when it was announced that a remake of George A. Romero’s The Crazies (1973) was announced. It was a low-budget cautionary tale about the inhabitants of a town that go insane after being exposed to a top secret government toxin code named Trixie. Fortunately, this new version doesn’t have Bay’s stink anywhere near it and is directed by Breck Eisner, freed from director’s jail where he had been imprisoned for Sahara (2005). This new version of The Crazies (2010) would succeed or fail on the decisions he made regarded the tone of the film, how closely he would stick to the original and how he would contemporize it to reflect our times.

Eisner grabs our attention right from the get-go and lets us know that something isn’t right in the small town of Ogden Marsh, Iowa. During a Little League baseball game, a disheveled-looking man walks out onto the field with a loaded shotgun. Sheriff David Dutton (Timothy Olyphant) is in attendance and confronts the man. Dutton is forced to shoot and kill the man. Something doesn’t seem right about the situation. Sure, the man was the town drunk but the tests come back and reveal that he had no alcohol in his system. Pretty soon, other townsfolk start acting strangely. The sheriff’s wife, Dr. Judy Dutton (Radha Mitchell) sees a man who appears listless and tired, repeating himself. Later that night, he burns down his house with his family in it. It doesn’t take long for the military to step in and round up and quarantine the townsfolk including the Duttons. Naturally, the military are unable to contain the threat and all hell breaks loose.

Breck Eisner does a nice job of gradually building up the threat and taking enough time to let us get to know the main characters so that we care about what happens to them later on. Early on, he creates a sense of place with several atmospheric establishing shots of the town. There are also several tension-filled moments, like when Judy is strapped to a gurney in government quarantine with a room full of others and an infected person enters the room and begins stabbing those still alive with a pitchfork. There is a real, palpable sense that she’s in danger. Another frighteningly effective scene takes place in a car wash as our heroes are besieged by the infected. There’s also an eerily beautiful shot of the town at night, ravaged by fire and destruction brought on by its infected inhabitants.

The Crazies is anchored by strong performances by Timothy Olyphant and Radha Mitchell. Playing the sheriff in this film seems like a warm-up, of sorts, for his current role as a U.S. Marshal in the T.V. show Justified. He brings just the right amount of affability and gravitas to the role while also having good chemistry with genre veteran Mitchell. She has a real knack for conveying the right mix of resilience and vulnerability while also imparting an intelligence to convincingly play a doctor. Plus, she’s got a great pair of lungs and can deliver an absolutely chilling scream when her character is being terrorized. Also worth mentioning is Joe Anderson who is quite good as the ever dependable deputy. He brings an exciting intensity to his role and does an excellent job realizing his character’s entire arc over the course of the film.

With 9/11, and with it the threats of Anthrax and SARS, as well as the success of chemical threat horror films like 28 Days Later (2002) and its sequel 28 Weeks Later (2007), it’s amazing that it took so long for a remake of The Crazies to be made. It’s really a testimony to how prescient Romero’s original film is that it’s just as relevant today as it was back in the 1970s. Thanks to the Patriot Act, if a town were infected by chemical warfare the government could do what happens in this film which makes it that much more terrifying. What makes this film a successful remake is the choices Eisner makes, like how he depicts the infected, shown in three distinct phases which is a nice variation on what Romero did in the original. One gets the impression watching The Crazies that the filmmakers put a lot of thought into this film. This isn’t just a carbon copy of the original. Unlike so many lazy remakes, this one examines some weighty themes and wraps them up in a very entertaining package.

Special Features:

There is an audio commentary by director Breck Eisner who, rather appropriately, starts off talking about how he got involved in the project. He wanted the film’s focus to be on the townsfolk, specifically David and Judy Dutton. He admits that initially he did not want to remake a Romero film but after watching the original again felt that he could increase the scale of it and update the premise to reflect contemporary issues. Eisner touches upon various aspects, including casting and locations, while also eloquently analyzing the film’s themes.

“Behind the Scenes with Breck Eisner” is a pretty standard if not well-made making of featurette that mixes interview soundbites with clips from the film. Eisner points out that an early version of the script he read had more of a balance between depicting the townsfolk and the military but he wanted to focus more on the town with an emphasis on horror rather than action.

“Paranormal Pandemics” takes a look at how the filmmaker designed the infected. The original design looked too much like zombies and so they went for a more vein-y look. We see actors getting fantastic-looking makeup applied. Eisner explains the three stages of infection and expanded on Romero’s original concept. They based the makeup on actual infections to give an added realism to the film.

“The George A. Romero Template” features filmmakers like Phantasm auteur Don Coscarelli and pundits from various horror film websites singing the praises of Romero’s films and how influential they are. Naturally, they talk about the original Crazies film and its relevance now.

“Make-Up Mastermind: Rob Hall in Action” goes into more detail about how they created the infected makeup. It’s pretty cool to see how they do it and how realistic it looks.

“The Crazies Motion Comic Episodes 1 & 2” features simplistic animated comic book art providing the backstory to the events depicted in the film.

“Visual Effects in Motion” takes a look at a few sequences before CGI was added and how, by stages, they achieved the end result. It is interesting to see how much a given sequence is enhanced by CGI.

Also included are a teaser and two theatrical trailers.

Finally, there is a “Behind the Scenes Photo Gallery” featuring shots of the cast and crew at work.

"...the main purpose of criticism...is not to make its readers agree, nice as that is, but to make them, by whatever orthodox or unorthodox method, think." - John Simon

"The great enemy of clear language is insincerity." - George Orwell

Tuesday, June 29, 2010

Friday, June 25, 2010

Tombstone

“A lot of people, a lot of studios, wished Tombstone

would just die. Kevin Costner was gearing up his film Wyatt Earp at the same

time, and it would have been easier if we’d just gone away. But Tombstone had a

lot of things going for it. First and foremost it had me.” – Kurt Russell

Almost every year there

seems to invariably be two similarly-themed films duking it out for box office

supremacy. One does better than the other because it comes out first or has a

bigger movie star in it or is just better in quality. In 1989, The Abyss out performed two other

underwater alien films, Leviathan and

Deepstar Six. A few years later, Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1991)

outperformed Robin Hood (1991) thanks

to the movie star power of Kevin Costner. In the late 1990s, you had the

competing asteroid disaster films with Armageddon

(1998) vs. Deep Impact (1998) and the

rival erupting volcano thrillers, Dante’s

Peak (1997) and Volcano (1997).

In the mid-‘90s, Hollywood

was at it again with competing Wyatt Earp biopics: Tombstone (1993) and Wyatt

Earp (1994). Despite the former having an earlier release date, the latter

featured Costner in the title role of the legendary lawman and with respected

screenwriter Lawrence Kasdan behind the camera. In addition, Tombstone was plagued with publicized production

problems as its director was fired early during principal photography only to

be replaced by another with almost no prep time. Amazingly, against the odds, Tombstone was not only made, but won the

box office showdown over the much longer, slower-paced Wyatt Earp. Audiences preferred the more entertaining,

action-packed Tombstone with its

fantastic cast of character actors led by none other than Kurt Russell. His

film delivered the goods, plain and simple. Despite the absolute critical

drubbing it received upon its theatrical release, it should be regarded among

the best westerns of the ‘90s alongside the likes of Unforgiven (1992) and Dead

Man (1995).

Based loosely on historical

events that took place in the American west during 1881-1882, Tombstone opens with a bang as a group

of outlaws known as the Cowboys, by the red sashes they wear, ride into a small

town and slaughter a large number of men because they killed two of their own.

The Cowboys are led by a man named Curly Bill (Powers Boothe). He’s such a

badass that he kills a groom on his wedding day and then laughs when his

right-hand man Johnny Ringo (Michael Biehn) guns down the priest who performed

the ceremony. These are clearly bad men not to be messed with.

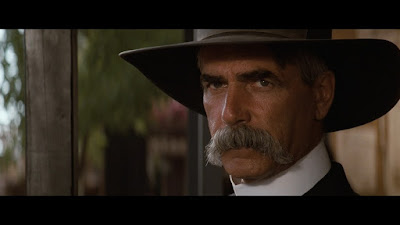

Meanwhile, Wyatt Earp

(Russell), his two brothers, Virgil (Sam Elliott) and Morgan (Bill Paxton), and

their wives arrive in Tombstone. They are retired lawmen looking to settle down

and make some money in this boomtown. We are soon introduced to Wyatt’s friend,

Doc Holliday (Val Kilmer), a sickly-looking gambler suffering from tuberculosis

but still possessing a deadly sense of humor and an even deadlier way with

guns. The Earps quickly learn the lay of the land: there’s plenty of money to

be made, just don’t cross the Cowboys. Wyatt stakes his claim early on when he

takes over a hard luck gambling joint and like that the Earps are in business

with Doc soon joining them.

It doesn’t take long for

Curly Bill to cross paths with Wyatt, and Johnny Rico to have words with Doc –

in Latin to be exact. It becomes readily apparent that these two are each

other’s opposites. Rico shows off his incredibly fast and dexterous gunhandling

skills to which Doc counters by mimicking Rico’s demonstration only in mocking

fashion with the mug he drinks alcohol from. A local actress named Josephine

Marcus (Dana Delany) catches Wyatt’s eye. He’s not only captivated by her

beauty, but intrigued by her assertive nature and zest for life. Wyatt’s

opium-addicted shrew of a wife Mattie Blaylock (Dana Wheeler-Nicholson) doesn’t

stand a chance against this free spirit.

Trouble arises when Curly

Bill, high as a kite on opium, shoots and kills the town’s kindly old marshal (Harry Carey, Jr.) forcing Wyatt to knock the outlaw out. He throws him in jail but

not before making enemies with the rest of his buddies. The town’s mayor (Terry O’Quinn) puts pressure on the Earps to become lawmen once again by appealing to

their innate moral sense of right and wrong. Pretty soon Virgil becomes the new

marshal and Morgan his deputy, much to Wyatt’s chagrin. He doesn’t want to get

involved, he’s just interested in making money and keeping a low profile. It

doesn’t take a rocket scientist to figure out that there’s going to be a showdown

between the Earps and the Cowboys.

Once Wyatt dusts off his

Peacemaker revolver, you just know that the killings are gonna start soon. This

culminates in the famous shoot-out at the OK Corral. There’s a fantastic shot,

courtesy of the late-great cinematographer William A. Fraker, of the Earps and

Doc walking down mainstreet with a burning building behind them as they

confront some Cowboys. This gunfight is hardly a glorious one and afterwards

Wyatt and Morgan deeply regret what happened. They never wanted things to go

this far.

Naturally, retribution for

what the Earps have done comes on a dark and stormy night (there’s one thing

you can say about this film is that it’s not subtle). By the end of it, one

Earp is dead and one seriously wounded, all at the hands of the Cowboys. As the

cliché goes, “this time its personal,” and the once reserved Wyatt becomes a

vessel of vengeance with those immortal words, “You called down the thunder,

well now you got it!” With Doc by his side and a few ex-Cowboys backing them

up, Wyatt systematically decimates the outlaws’ ranks, working his way up to

the food chain to the inevitable showdown with Curly Bill and Johnny Rico.

Russell was drawn to this

film because it took a look at what happened to Earp after the gunfight at the

O.K. Corral and showed a darker side of the man. Russell was fascinated in

exploring the aftermath of this famous fight: “Wyatt Earp went on a serious

binge of killing. There is no way to determine now how many people he actually

did kill, but it was a lot. He was a man who tilted over the edge. He went

nuts. Something inside him finally broke.”

How great is Val Kilmer as

Doc Holliday? He plays the man as a genteel southern gentleman armed with dry

wit and a lightning fast quick draw. He gets the lion’s share of the film’s

most memorable lines and they are often little asides, like when he beats a

clearly frustrated man at poker and says upon revealing his cards, “Isn’t that

a daisy?” And then, when the man insults him, Doc, in a mock-hurt tone, wonders

if they’re still friends and says, “You know Ed, if I thought you weren’t my

friend, I just don’t think I could bear it.” It’s the way Kilmer says these

words that makes the scene so much fun to watch. You can just tell that he’s

having a blast with this role as evident by how deeply immersed he is in Doc on

every level, like the way he carries himself in a given scene, his languid body

language, his sickly pallor, and his cultured accent. The combination of all

these elements results in one of the most memorable takes on Doc Holliday ever

committed to film.

Faced with playing off such

a flamboyant character, Kurt Russell wisely plays straight man to Kilmer.

Initially, he plays Wyatt as a genial enough fellow, interested in making money

and avoiding any trouble that might lead to him putting on a lawman’s badge

again. However, that doesn’t mean he’s a pushover either as evident in the

scene where he bitch slaps an arrogant gambler (an obnoxious Billy Bob

Thornton) at a down-on-its-luck saloon and then browbeats him: “You gonna do

something or just stand there and bleed?” Russell has that fantastic

no-nonsense stare that lets you know right away that Wyatt means business.

However, as he gets dragged into a feud with the Cowboys his demeanor changes

and he becomes a more stoic figure until going into full killing mode,

transforming into a frightening force of nature. It is refreshing to see that

Russell is not afraid to show the darker aspects of Wyatt and was able to do so

thanks to the success of Clint Eastwood’s dark, complicated western, Unforgiven.

It’s

something of an understatement to say that Tombstone’s

cast is an embarrassment of riches and a treasure trove for fans of character

actors. Where else do you get to see Stephen (Manhunter) Lang threaten Sam (The

Big Lebowski) Elliott? Or see Jason Priestley swoon over Billy (Titanic) Zane? Or have Michael (Aliens) Biehn sparring verbally in Latin

with Val (Heat) Kilmer? Powers

Boothe, one of the great, under-appreciated character actors, plays Curly Bill

with gusto and bravado, which is in sharp contrast to Biehn’s quiet intensity

as Johnny Rico who is no crazed, one-dimensional baddie – he quotes from the

Bible and speaks Spanish and Latin fluently.

The screenplay by Kevin Jarre pushes all the right buttons as we quickly identify with the Earps and

want to see the Cowboys get their much-deserved comeuppance. It is also full of

colorful period lingo: “Skin that smoke wagon and see what happens,” or “I’m

getting tired of your gas. Now jerk that pistol and go to work.” The dialogue

absolutely crackles with energy and it has the perfect cast to bring it vividly

to life so that it leaps off the page. Tombstone

is one of those rare films where you can see the actors enjoying their roles

because they finally have juicy parts that they can sink their teeth into.

In 1989, first-time

writer/director Kevin Jarre was going to make Tombstone with Kevin Costner but then the actor decided that he

wanted to do a film about Wyatt Earp and not Tombstone. Producer James Jacks

championed Jarre’s screenplay for the production company he formed in

partnership with Sean Daniel, former production chief at Universal Pictures.

Jacks originally approached Universal but they deemed the project too risky and

rejected it. In January 1992, Jarre’s script about Earp was on verge of being

made into a film but it was almost shelved when Costner announced his own Earp

film to be written and directed by Lawrence Kasdan for Warner Brothers. At the

time, Jarre claimed that Costner’s move was “an attempt to crush my picture.”

Perhaps not so coincidentally, Brad Pitt, who was excited about starring in Tombstone, backed off once Costner’s

project was announced.

Jarre’s script was ready to

shoot, all he needed was a cast. However, Michael Ovitz’s powerful Creative

Artists Agency was backing Costner and Tombstone’s

producers, Jacks and Daniel, could not attract a movie star big enough to get a

Hollywood studio interested in backing the film. Pitt was represented by

Ovitz’s agency and at the time Jacks said, “CAA is telling people our movie

won’t happen.” Fortunately, they caught a break when Kurt Russell’s old agent

at William Morris slipped a copy of the script to the actor who was now at CAA.

He agreed to play Earp and this attracted the likes of Val Kilmer, Sam Elliott,

Michael Biehn, and Powers Boothe. Russell then took the project to financier

Andrew Vajna’s Cinergi Productions, which had a distribution deal with Disney.

Vajna agreed to make the film for $25 million. Originally, Jarre and Russell

wanted Willem Dafoe to play Doc Holliday but Disney refused to release it with

him in the role because of portrayal of Jesus Christ in the controversial

Martin Scorsese film, The Last Temptation

of Christ (1988), and told the film’s producers to cast Kilmer instead.

Filming began in May 1992 on

location in Mescal, Arizona. First-time director Jarre got into trouble early

on. Reportedly, he wouldn’t think visually and refused advice from the film’s

veteran cinematographer and six-time Academy Award nominee William Fraker. Sam

Elliott remembers, “I knew from the third day Kevin couldn’t direct. He wasn’t

getting the shots he needed.” According to Jacks, Jarre was “shooting in an

unconventional old-fashioned, John Ford style, with very few close-ups.” Some cast

and crew-members felt that the tight shooting schedule didn’t help, especially

for an inexperienced director like Jarre. Jacks realized that Jarre wasn’t very

well-prepared when the filmmaker would disappear for hours to ride his horse.

This left the cast and crew feeling abandoned. In retrospect, Jacks regretted

not insisting that Jarre direct a couple of smaller films before “attempting

something as demanding and complicated as a big western.”

Actor Michael Rooker felt

that “from the beginning they allotted too little time to do this movie.” In

August 1992, after four weeks and with Russell and Fraker ready to quit, Vajna

fired Jarre. Still committed to the film, the cast and crew stuck together and

were determined to finish what they started. Russell called Sylvester Stallone

(they had worked together on Tango and

Cash) and told him he needed a director to come in on short notice.

Stallone recommended George P. Cosmatos who he had worked with on Rambo: First Blood, Part 2 (1985).

Cosmatos arrived on location with only three days of preparation and Russell

told him, “I’m going to give you a shot list every night, and that’s what’s

going to be.” Russell and Val Kilmer met with Cosmatos and came to an

understanding: Cosmatos would focus on finishing the film on schedule while

Russell trimmed the unwieldy script and oversee the 85 cast members.

Russell and Jacks cut down

the script’s scenes on a daily basis, eliminating 30 pages so that the focus

was on the relationship between Earp and Doc Holliday. From the beginning,

Russell realized that these pages needed to be taken out but Jarre failed to do

this and when he was fired Russell was the only one left who knew the script.

In an attempt to gain the trust of the cast, Russell reduced his part in the

script. Cosmatos agreed with these changes but some cast-mates weren’t too

happy with having their parts reduced. Elliott said, “Initially, the screenplay

was one of the best I’ve ever read. If I was given the screenplay as it is now,

I’d have to pass on it.” He felt that Russell and Jacks, “eliminated the

connective tissue, took the character development out.” According to Kilmer,

Jarre’s original script had a subplot and a story told for every main character

and none of them made it into the final film.

Cosmatos ended up reshooting

almost the entire film with only 15 bits and pieces shot by Jarre making it

into the final cut. The veteran journeyman director brightened the film’s color

palette and added an opening Mexican wedding/massacre sequence as well as two action

montages in the last half hour. His working methods resulted in two script

supervisors and half the art department leaving for other jobs, quitting or

being fired. According to production designer Catherine Hardwicke, “He was

demanding. Some people freaked out.” In frustration, Fraker quit three times.

At one point, he got into a screaming match with Cosmatos and Jacks intervened,

persuading the cinematographer to stay.

Principal photography

finished on August 29, 1992 after 88 days. After the dust settled, the film had

gone $2-3 million over budget. The filmmakers had to rush through

post-production in order to make the Christmas Day opening mandated by Disney.

Russell said, “I don’t know if Kevin would have been able to realize the film

he had in his mind. We might still be shooting his movie. I helped him by

making sure we got the movie made.”

Tombstone

received overwhelmingly negative reviews from critics. The New York Times’ Stephen Holden wrote, “Tombstone is, finally, a movie that wants to have it both ways. It

wants to be at once traditional and morally ambiguous. The two visions don't

quite harmonize.” In his review for the Washington

Post, Richard Harrington wrote, “A major problem throughout the film is the

opting for style over substance, whether in terms of dark visuals or stark

dialogue ... But too much of Tombstone

rings hollow. In retrospect, not much happens and little that does seems

warranted.” Entertainment Weekly gave

the film a “C-“ rating and Owen Gleiberman wrote, “A preposterously inflated

135 minutes long, Tombstone plays

like a three-hour rough cut that's been trimmed down to a slightly shorter

rough cut.” USA Today gave the film

one and a half stars and wrote, “Director George Cosmatos brings nothing new to

this Wyatt Earp saga except leftover bullets from previous films Cobra and Rambo: First Blood Part II.” In his review for the Globe and Mail, Geoff Pevere wrote,

“Forget shifting zeitgeists or the decline of American idealism. What's really

killing westerns are bloated, free-range turkeys like Tombstone.”

Critics need to lighten up

and enjoy Tombstone for what it is: a

fun, popcorn movie that is all about mustaches: the Earps all sport big bushy

ones that threaten to consume their faces, while the bad guys all sport thinner

ones with goatees or beards. The wild card in all of this is Doc who sports a

thin mustache suggesting that he’s a bad guy as he does cheat at cards, but

he’s also Wyatt’s friend and is very loyal to him and his brothers, even

willing to back them up at the OK Corral gunfight. Ultimately, Tombstone is about male friendship, in

particular the intense and unusual bond between Doc and Wyatt. Early on, it

takes on a playful tone as Doc has some fun with Wyatt’s obvious attraction to

Josephine. Even though they aren’t related by blood they might as well be

brothers as they’re willing to die for each other. They don’t verbalize it but

it’s all in the eyes and this is nicely realized by Kilmer and Russell. It’s

hard not to be moved by the final scene between their two characters.

When all was said and done,

Kevin Costner’s Wyatt Earp cost $60

million and was unable to recoup it as Tombstone

came out first and stole its thunder, grossing a respectable $55 million. To

add insult to injury, Disney released Tombstone

on home video right before Wyatt Earp’s

theatrical release and it did strong rental business. Tombstone is an epic western that has all the right ingredients:

stoic lawmen, dastardly outlaws, rousing montages, beautiful women, angry

proclamations, emotional death bed speeches, and, of course, exciting

shoot-outs. George P. Cosmatos’ direction is no frills – strictly meat and

potatoes, which is just right for this straightforward tale. While the gun

battles are noisy and chaotic, you always know where everyone is and what’s

going on. It may not be a brooding meditation on violence like Unforgiven or push the boundaries of the

genre like Dead Man, but Tombstone is an unabashed crowd pleaser

in the classic western tradition.

SOURCES

Arnold, Gary. “Tombstone Point-Blank.” Washington

Times. December 19, 1993.

Beck, Henry Cabot. “The

‘Western’ Godfather.” True West.

October 1, 2006.

EW Staff. “Shoot First (Ask

Questions Later).” Entertainment Weekly. December 24, 1993.

Grimes, William. “How to Fix

a Film at the Very Last Minute (Or Even Later).” The New York Times. May

15, 1994.

Gristwood, Sarah. “To Hire

and to Fire.” The Guardian. January 18, 1994.

Portman, Jamie. “Wyatt

Earp’s Tombstone Gets Revisionist

Engraving.” Toronto Star. December 20, 1993.

Thompson, Anne. “Dueling

Deals.” Entertainment Weekly. January 8, 1993.

Thompson, Anne. “Quiet

Earp.” Entertainment Weekly. July 15, 1994.

Tuesday, June 22, 2010

Versatile Blogger Award

It's always nice to receive kudos for you work for the simple fact that it reaffirms someone out there is reading your stuff! filmgeek over at the excellent blog Final Cut bestowed this blog the and in keeping with the good will I'm passing on this award to other blogs that I enjoy reading and that inspire me. Here are the deets:

1. Thank the person who gave you this award (done)

2. Share seven things about yourself

3. Pass the award along to 15 who you have recently discovered and who you think fantastic for whatever reason (in no particular order)

4. Contact the blogs you picked and let them know about the award.

The Cooler

She Blogged By Night

John Kenneth Muir's Reflections on Film/TV

Twenty Four Frames

Ferdy on Films

Cinema Viewfinder

Dinner with Max Jenke

Junta Juleil's Culture Shock

Sugar and Spice

Lazy Thoughts from a Boomer

Hugo Stiglitz Makes Movies

Mr. Peel's Sardine Liqueur

Things That Don't Suck

Technicolor Dreams

Musings of Sci-Fi Fanatic

Friday, June 18, 2010

Frantic

By the time he had made Frantic (1988), filmmaker Roman Polanski was in need of a commercial hit at the box office. His previous film Pirates (1986) bombed spectacularly both with audiences and critics. In a canny move, he cast Harrison Ford as the lead actor in his new film. As luck would have it, Ford was in a very interesting place, career-wise. Thanks to the massive success of the Star Wars and Indiana Jones films, he had the clout and the confidence to try riskier films that played around with the public’s perception of him. With Blade Runner (1982), Ford played an emotionally distant cop hunting down replicants in a future dystopia. In Witness (1985), he played a gruff Philadelphia cop who hides out in Amish country when he uncovers corruption in his department. Mosquito Coast (1986) may have been his most challenging role as an inventor who moves his entire family to the jungles of South America and gradually loses his mind.

Finally, he took a stab at comedy with Working Girl (1988) playing a no-nonsense business executive helping a plucky young secretary masquerading as a financial executive broker an ambitious merger deal. Throw in Frantic and you have a pretty diverse collection of films that saw Ford unafraid to play abrasive even sometimes unlikable characters. With Polanski’s film, Ford would be on the director’s turf, thrust in a world of moral ambiguity with a dash of paranoia. It made for a fascinating clash of styles and results in an excellent thriller and something of an under-appreciated work in both men’s filmography.

“Do you know where you are?” These are the first words spoken in Frantic and they foreshadow the feelings of displacement that the film’s protagonist will experience. Sondra Walker (Betty Buckley) says these words to her husband Dr. Richard Walker (Harrison Ford) as they drive from the airport to their Paris hotel in a taxi cab. He’s there to attend a convention and en route their taxi develops a flat tire. The driver is unable to fix it which is not a good start to the Walkers’ trip so far and a bad omen for what is to come.

Polanski establishes the dynamic between Richard and Sondra in a relatively short time as they get settled in their hotel room. Harrison Ford and Betty Buckley do an excellent job portraying a couple that have clearly been married for some time. This is evident in the familiar shorthand between them, like how they act towards each other, the playful needling Sondra gives her husband about the swanky luncheon he’s supposed to have with the chairman of the convention at the Eiffel Tower. This early scene also establishes how out of his element Richard is as she points out that he doesn’t speak French and doesn’t even know how to use the hotel room phone. We see how easily they can get on each other’s nerves and how they quickly reconcile like any couple who has been in love for a long period of time.

They soon discover that Sondra grabbed the wrong suitcase at the airport and has someone else’s luggage. Richard takes a shower and in those few minutes his wife disappears. Polanski places the camera in the shower with Richard so that we see and hear what he does. The camera slowly pushes in in an ever-so slightly way – it’s subtle but does make you wonder what’s happening in the other room. Initially, Richard most likely assumes that Sondra went out to buy some clothes or is in another part of the hotel. However, enough time passes that he becomes understandably concerned and decides to search the hotel lobby. Polanski’s camera follows Richard from a distance so that he looks slightly diminished and out of sorts in this strange and disorienting place.

When the hotel staff is unable to help him, Richard hits the streets. We quickly see how disadvantaged he is as he wanders into a flower shop and tries to explain to the two people who work there about his wife. They don’t speak English and assume that he wants to buy her flowers. He has slightly better luck at a nearby bar when a scruffy-looking, bearded barfly (played by Jean-Pierre Jeunet regular Dominique Pinon) claims that a couple of his friends saw Sondra being forcibly pushed into a car. When he asks the man to take him to the spot where it happened he finds her bracelet on the ground.

Richard goes to the local cops and then the American Embassy but neither are much help, mired as they are in bureaucracy and paperwork. Understandably frustrated, he decides to conduct his own investigation, one that takes him through a Paris you won’t see in any tourism ads. Along the way, he tries some cocaine (?!), discovers a dead body and meets Michelle (Emmanuelle Seigner), a mysterious and beautiful young woman who picked up Sondra’s suitcase. With Michelle’s help, he begins to figure out what happened to his wife.

Harrison Ford is quite good as a man clearly out of his element, the classic stranger in a strange land. He plays a normal guy thrust into extraordinary circumstances. As the film progresses, Richard becomes more savvy and uses his intelligence to piece things together. This is not your typical man-of-action role that we normally associate with Ford. For example, there’s a nice scene where Richard takes a break from searching for his wife and calls home just so he can hear the reassuring sound of his daughter’s voice. Ford does a nice job of showing his character on the verge of tears, trying to keep it together as he chit chats with one of his children who is oblivious as to what is happening to her parents in Paris. Polanski lets the scene play out in one long, uninterrupted take, the camera gradually pushing in on Ford and focusing on his visibly upset face. He conveys a touching vulnerability in this scene and watching this film again is a sobering reminder of what an excellent actor he can be.

Of note, the always reliable character actor John Mahoney has a minor role as an ineffectual American bureaucrat who does little to help Richard and proves to be more of an annoyance than anything else. And what kind of influence did Grace Jones have on Polanski to get her song “I’ve Seen That Face Before (Libertango)” played so often and prominently in the film? The lyrics to the song are certainly appropriate to what Richard is going through in a kind of New Wave meets film noir way as Jones describes the dark side of the nightlife in Paris.

After the failure of Pirates, Polanski began work in Paris on an adaptation of the Belgian comic strip character Tin-Tin with screenwriter Melissa Mathison, Ford’s then-wife. The actor flew in to visit her just as Warner Brothers asked Polanski if he had a project. The director remembers, “I said yes, of course; it was so good to be asked, because my last film, Pirates, was such a flop, so painful in every way, I was in the deepest depression.” However, he had to come up with an idea and thought of a thriller set in Paris. Polanski talked to his writing partner for 25 years, Parisian screenwriter Gerard Brach about a story and then he told Ford who agreed to do the film. The studio agreed to finance and distribute it with a budget under $20 million. With Frantic, Polanski wanted to show the Paris he knew, “the one with garbage collectors, not the one in Irma La Douce.”

The rest of the cast fell into place with Polanski being impressed by the maturity of Betty Buckley in her audition tape, and 21-year-old ex-model Emmanuelle Seigner who the director had been living with for three years. On set, Polanski has a reputation for being a very hands-on director in order to get exactly what he wants out of an actor. For the scene where Ford’s character almost falls off a steep roof, he and Polanski actually climbed out on it to work out the shots. Either one of them could have been killed had they slipped. Buckley remembers that during the climactic shoot-out, “I knelt beside a woman who’d been shot, as Harrison checked out her wounds, Roman directed me to see a horrible injury that wasn’t actually there.” Unhappy with her reaction after multiple takes, Polanski secretly told his makeup man to create extremely gory wounds. On the next take, Buckley remembers, “it was so ugly I wanted to vomit. I totally lost it on camera, which was not my choice. But Roman got exactly what he wanted.”

Most critics heralded Frantic as a return to form for Polanski after the disappointing Pirates. Roger Ebert gave the film three out of four stars and wrote, “even with its excesses, Frantic is a reminder of how absorbing a good thriller can be.” In her review for The New York Times, Janet Maslin praised Ford’s performance: “He's able to convey great determination, as well as a restraint that barely masks the character's mounting rage, and he makes a compelling if rather uncomplicated hero.” The Washington Post’s Hal Hinson wrote, “What Frantic signals is a return to form for the turbulent Pole. It’s not great, but it’s good enough to be excited about, both for itself and the promise it holds out for the future.” In his review for the Globe and Mail, Jay Scott wrote, “The humor, much of it built into Harrison Ford’s phenomenal characterization of a reasonable man drowning in irrationality, is deft and sly.” Finally, Newsweek magazine’s Jack Kroll felt that “Frantic is Polanski’s best movie since the 1974 Chinatown.”

Frantic’s premise is pure Hitchcock albeit with Polanski’s trademark perversity. The screenplay only doles out information as Richard uncovers it which helps us identify with him – we only know what he does. The director doesn’t skimp on the thriller aspects of the film either. There’s a tension-filled scene where Richard scrambles across a very precarious rooftop with the piece of luggage that everyone seems to be after. There’s also a car chase through the streets of Paris as Richard pursues the men who have his wife. Unlike most thrillers made nowadays that are all frenetic action and spastic editing, Polanski lets his story breath. He takes the time to establish the main characters and allows us to empathize with Richard’s situation, one in which is eerily relevant to today’s political climate and feeds on the anxiety Americans have with traveling abroad. Polanski still fulfills genre conventions at the film’s climax with an exciting shoot-out but delivers a bittersweet ending reminiscent of his 1970s output and this must’ve been jarring to audiences at the time expecting an uplifting ending more typical of Ford’s mainstream work in the 1980s.

Check out Movie City News which did a really nice appreciation of Polanski's film.

SOURCES

McBride, Stewart. "Roman Empire." The Advertiser. March 12, 1988.

Scott, Jay. "Polanski Has Transformed Loss into Artistic Gain." Globe and Mail. February 28, 1988.

Finally, he took a stab at comedy with Working Girl (1988) playing a no-nonsense business executive helping a plucky young secretary masquerading as a financial executive broker an ambitious merger deal. Throw in Frantic and you have a pretty diverse collection of films that saw Ford unafraid to play abrasive even sometimes unlikable characters. With Polanski’s film, Ford would be on the director’s turf, thrust in a world of moral ambiguity with a dash of paranoia. It made for a fascinating clash of styles and results in an excellent thriller and something of an under-appreciated work in both men’s filmography.

“Do you know where you are?” These are the first words spoken in Frantic and they foreshadow the feelings of displacement that the film’s protagonist will experience. Sondra Walker (Betty Buckley) says these words to her husband Dr. Richard Walker (Harrison Ford) as they drive from the airport to their Paris hotel in a taxi cab. He’s there to attend a convention and en route their taxi develops a flat tire. The driver is unable to fix it which is not a good start to the Walkers’ trip so far and a bad omen for what is to come.

Polanski establishes the dynamic between Richard and Sondra in a relatively short time as they get settled in their hotel room. Harrison Ford and Betty Buckley do an excellent job portraying a couple that have clearly been married for some time. This is evident in the familiar shorthand between them, like how they act towards each other, the playful needling Sondra gives her husband about the swanky luncheon he’s supposed to have with the chairman of the convention at the Eiffel Tower. This early scene also establishes how out of his element Richard is as she points out that he doesn’t speak French and doesn’t even know how to use the hotel room phone. We see how easily they can get on each other’s nerves and how they quickly reconcile like any couple who has been in love for a long period of time.

They soon discover that Sondra grabbed the wrong suitcase at the airport and has someone else’s luggage. Richard takes a shower and in those few minutes his wife disappears. Polanski places the camera in the shower with Richard so that we see and hear what he does. The camera slowly pushes in in an ever-so slightly way – it’s subtle but does make you wonder what’s happening in the other room. Initially, Richard most likely assumes that Sondra went out to buy some clothes or is in another part of the hotel. However, enough time passes that he becomes understandably concerned and decides to search the hotel lobby. Polanski’s camera follows Richard from a distance so that he looks slightly diminished and out of sorts in this strange and disorienting place.

When the hotel staff is unable to help him, Richard hits the streets. We quickly see how disadvantaged he is as he wanders into a flower shop and tries to explain to the two people who work there about his wife. They don’t speak English and assume that he wants to buy her flowers. He has slightly better luck at a nearby bar when a scruffy-looking, bearded barfly (played by Jean-Pierre Jeunet regular Dominique Pinon) claims that a couple of his friends saw Sondra being forcibly pushed into a car. When he asks the man to take him to the spot where it happened he finds her bracelet on the ground.

Richard goes to the local cops and then the American Embassy but neither are much help, mired as they are in bureaucracy and paperwork. Understandably frustrated, he decides to conduct his own investigation, one that takes him through a Paris you won’t see in any tourism ads. Along the way, he tries some cocaine (?!), discovers a dead body and meets Michelle (Emmanuelle Seigner), a mysterious and beautiful young woman who picked up Sondra’s suitcase. With Michelle’s help, he begins to figure out what happened to his wife.

Harrison Ford is quite good as a man clearly out of his element, the classic stranger in a strange land. He plays a normal guy thrust into extraordinary circumstances. As the film progresses, Richard becomes more savvy and uses his intelligence to piece things together. This is not your typical man-of-action role that we normally associate with Ford. For example, there’s a nice scene where Richard takes a break from searching for his wife and calls home just so he can hear the reassuring sound of his daughter’s voice. Ford does a nice job of showing his character on the verge of tears, trying to keep it together as he chit chats with one of his children who is oblivious as to what is happening to her parents in Paris. Polanski lets the scene play out in one long, uninterrupted take, the camera gradually pushing in on Ford and focusing on his visibly upset face. He conveys a touching vulnerability in this scene and watching this film again is a sobering reminder of what an excellent actor he can be.

Of note, the always reliable character actor John Mahoney has a minor role as an ineffectual American bureaucrat who does little to help Richard and proves to be more of an annoyance than anything else. And what kind of influence did Grace Jones have on Polanski to get her song “I’ve Seen That Face Before (Libertango)” played so often and prominently in the film? The lyrics to the song are certainly appropriate to what Richard is going through in a kind of New Wave meets film noir way as Jones describes the dark side of the nightlife in Paris.

After the failure of Pirates, Polanski began work in Paris on an adaptation of the Belgian comic strip character Tin-Tin with screenwriter Melissa Mathison, Ford’s then-wife. The actor flew in to visit her just as Warner Brothers asked Polanski if he had a project. The director remembers, “I said yes, of course; it was so good to be asked, because my last film, Pirates, was such a flop, so painful in every way, I was in the deepest depression.” However, he had to come up with an idea and thought of a thriller set in Paris. Polanski talked to his writing partner for 25 years, Parisian screenwriter Gerard Brach about a story and then he told Ford who agreed to do the film. The studio agreed to finance and distribute it with a budget under $20 million. With Frantic, Polanski wanted to show the Paris he knew, “the one with garbage collectors, not the one in Irma La Douce.”

The rest of the cast fell into place with Polanski being impressed by the maturity of Betty Buckley in her audition tape, and 21-year-old ex-model Emmanuelle Seigner who the director had been living with for three years. On set, Polanski has a reputation for being a very hands-on director in order to get exactly what he wants out of an actor. For the scene where Ford’s character almost falls off a steep roof, he and Polanski actually climbed out on it to work out the shots. Either one of them could have been killed had they slipped. Buckley remembers that during the climactic shoot-out, “I knelt beside a woman who’d been shot, as Harrison checked out her wounds, Roman directed me to see a horrible injury that wasn’t actually there.” Unhappy with her reaction after multiple takes, Polanski secretly told his makeup man to create extremely gory wounds. On the next take, Buckley remembers, “it was so ugly I wanted to vomit. I totally lost it on camera, which was not my choice. But Roman got exactly what he wanted.”

Most critics heralded Frantic as a return to form for Polanski after the disappointing Pirates. Roger Ebert gave the film three out of four stars and wrote, “even with its excesses, Frantic is a reminder of how absorbing a good thriller can be.” In her review for The New York Times, Janet Maslin praised Ford’s performance: “He's able to convey great determination, as well as a restraint that barely masks the character's mounting rage, and he makes a compelling if rather uncomplicated hero.” The Washington Post’s Hal Hinson wrote, “What Frantic signals is a return to form for the turbulent Pole. It’s not great, but it’s good enough to be excited about, both for itself and the promise it holds out for the future.” In his review for the Globe and Mail, Jay Scott wrote, “The humor, much of it built into Harrison Ford’s phenomenal characterization of a reasonable man drowning in irrationality, is deft and sly.” Finally, Newsweek magazine’s Jack Kroll felt that “Frantic is Polanski’s best movie since the 1974 Chinatown.”

Frantic’s premise is pure Hitchcock albeit with Polanski’s trademark perversity. The screenplay only doles out information as Richard uncovers it which helps us identify with him – we only know what he does. The director doesn’t skimp on the thriller aspects of the film either. There’s a tension-filled scene where Richard scrambles across a very precarious rooftop with the piece of luggage that everyone seems to be after. There’s also a car chase through the streets of Paris as Richard pursues the men who have his wife. Unlike most thrillers made nowadays that are all frenetic action and spastic editing, Polanski lets his story breath. He takes the time to establish the main characters and allows us to empathize with Richard’s situation, one in which is eerily relevant to today’s political climate and feeds on the anxiety Americans have with traveling abroad. Polanski still fulfills genre conventions at the film’s climax with an exciting shoot-out but delivers a bittersweet ending reminiscent of his 1970s output and this must’ve been jarring to audiences at the time expecting an uplifting ending more typical of Ford’s mainstream work in the 1980s.

Check out Movie City News which did a really nice appreciation of Polanski's film.

SOURCES

McBride, Stewart. "Roman Empire." The Advertiser. March 12, 1988.

Scott, Jay. "Polanski Has Transformed Loss into Artistic Gain." Globe and Mail. February 28, 1988.

Friday, June 11, 2010

The Doors

Anticipation was high when it was announced that Oliver Stone would be filming a biopic about the popular rock band the Doors. With Platoon (1986) and Born on the Fourth of July (1989), he was gaining a reputation for being the premiere chronicler of America in the 1960s so it made sense that he would tackle that decade’s most famous (and infamous) musical acts. The question remained, what kind of approach would Stone take on the material? Many books had been written by journalists, people that knew him and even by members of the band itself, all with their own perspective and opinion on what the Doors meant to them and to popular culture. The world found out what Stone’s take was on March 1, 1991 when The Doors was released to wildly mixed reviews and strong box office. While many critics felt that Val Kilmer delivered an excellent performance as the band’s lead singer Jim Morrison, they felt that the film dwelled too much on his darker aspects and excesses and that Stone played fast and loose with the facts.

One should look at The Doors much like Stone’s subsequent film JFK (1992), as a mythical take on historical figures and events and not as documentary-like authenticity. I find The Doors to be a big, bloated, fascinating mess of a film that reflects the tumultuous times of the ‘60s. Despite the miscasting of a few roles and the rather one-sided view we get of Morrison, Stone’s film is a beautifully-shot acid trip through the ‘60s with some of the best choreographed live concert sequences every recreated on film. Best of all, it brought the Doors’ music back into the mainstream, reminded everyone what a brilliant band they were, and how much they influenced and reflected their times.

The film starts off with Morrison (Val Kilmer) recording An American Prayer and reciting lines that rather nicely apply to the beginning of this biopic. Then, Stone takes us back to New Mexico, 1949 when the singer was just a boy. As Robert Richardson’s camera floats over desolate, sun-drenched desert, the first atmospheric strains of “Riders on the Storm” plays over the soundtrack. Right from the get-go, Stone establishes the mythical approach he plans to adopt for the film by recreating a popular story told by Morrison that as a young boy his family passed by a car accident involving an elderly Native American Indian. As the story goes, at the moment when he died, his spirit left his body and went into the young Morrison. The story was meant to explain Morrison’s fascination with shamanism and mysticism.

We quickly jump to Venice Beach, 1965 where Morrison is attending film school at UCLA along with Ray Manzarek (Kyle MacLachlan). He also meets Pamela Courson (Meg Ryan), who would go on to become the great love of his life, and they quickly become romantically involved. The appearance of these two people exposes early on one of the film’s flaws – the miscasting of Kyle MacLachlan as Manzarek and Meg Ryan as Pamela. Whereas from his first appearance on-screen, you instantly accept Val Kilmer as Morrison, MacLachlan comes across as too stiff and the dialogue doesn’t sound natural coming out of his mouth. Not to mention, his wig is a distraction. With Ryan, it is her identification with romantic comedies like When Harry Met Sally... (1989) and Joe Versus the Volcano (1990) that makes it so hard to believe her as a free-spirited flower child that eventually transforms into a promiscuous drug user. In scenes where Pamela is supposed to come across as naive, Ryan conveys a clueless vacancy. It’s too bad because she would go on to demonstrate an ability to tap into a darker side with Prelude to a Kiss (1992) and more significantly with the little-seen Flesh and Bone (1993). However, with The Doors, she is clearly out of her comfort zone and it is glaringly obvious.

From there we go to that fateful day when Morrison sang some of the lyrics to “Moonlight Drive” to Manzarek and they proposed starting a band, coming up with the name, the Doors. Stone jumps to the band now with drummer John Densmore (Kevin Dillon) and guitarist Robby Krieger (Frank Whaley) rehearsing “Break on Through (To the Other Side).” This is a really strong scene as it shows the genesis for their biggest song, “Light My Fire” and Stone makes a point of showing that Morrison didn’t write all of their songs. Stone also shows how they all contributed to the song’s evolution that resulted in the classic it became. I also like how we see the Doors starting out, playing a small dive on the Sunset Strip called London Fog. Morrison is still so shy on stage that he can’t face the audience. This is the film at its best, showing the band creating music and in action, performing live.

It goes without saying that The Doors truly comes to life during the concert scenes as all the theatrical stage lighting and dynamic camera movements showcases Richardson’s skill as one of the best cinematographers ever to get behind the camera. The warm colors he uses in the London Fog scenes conveys an intimacy representative of the small venue and symbolizes a band still learning their chops, both musically and how they perform in a live setting. Richardson really gets a chance to cut loose in the sequence where the band go out into the desert and take peyote. He employs all sorts of trippy effects and also creates some stunningly beautiful shots, like that of a blue sky populated by all kinds of fragmented clouds or a pan across a rocky formation with shadows creeping upwards, animated via time lapse photography.

Stone then segues to the Doors playing at the Whisky a Go Go in 1966 – the next step to the big time. We see them perform “The End,” an epic Oedipal nightmare. It’s a hypnotic song that shows how far the band had come. Morrison is no longer shy and commands the stage like no other before him. Kilmer is mesmerizing in this scene and you can see how fully committed he is to the role. It’s not just the ability to recreate Morrison’s signature moves but he has an uncanny knack to immerse himself in the singer’s headspace. In these concert scenes it is incredible to see the actor throw himself completely into them just as Morrison would.

In the spot-on casting department, it was an absolute delight to see Michael Wincott freed from the shackles of playing clichéd heavies and make an appearance as legendary music producer Paul Rothchild who worked on many of the Doors’ albums. He has a fantastic scene later on when he tries to get through to a drunken Morrison during an awful recording session and delivers an impassioned speech even though the singer tunes him out.

Stone’s film starts to lose its mind when the Doors arrive in New York City in 1967 and the way he presents the hysteria of their arrival is like the Second Coming of the Beatles. There are moments of amusing levity as Stone shows the obvious culture clash between the square staff at The Ed Sullivan Show when the producers try to be hip by talking to the band in their own “lingo” using words like “groovy” and “dig it” that sound forced and fabricated. The Doors are told to change a lyric in “Light My Fire” so as to satisfy standards and practices. Stone has a bit of fun with their televised appearance, fudging how Morrison defied the censors.

Stone shows the skyrocketing of Morrison’s ego and how he began to believe his own hype. He also suggests that Morrison really started to lose control when he and his bandmates attended a party at Andy Warhol’s The Factory. All sorts of pretentious weirdoes vie for Morrison’s attention. Manzarek sums it up best when he tells Morrison, “These people are vampires.” However, it’s when the rest of the band departs the party leaving Morrison to fend for himself that Stone suggests the moment when the first schism between them was created. The look of distrust on the singer’s face as his bandmates depart says it all. There is no one to keep his indulgent behavior in check. We are subjected to an unfortunate fey caricature of Warhol thanks to the usually reliable Crispin Glover. Hanging out with Nico and Warhol’s regulars brings out Morrison’s worst excesses which Richardson shoots like some kind of monstrous nightmare, a bad trip that we want desperately to end. This sequence starts Stone’s escalation of depicting Morrison’s self-destructive journey.

And so we get a scene where Morrison does cocaine with a self-professed witch (played by a vampy Kathleen Quinlan) and participates in a silly, over-the-top ceremony whose inclusion stops the narrative cold. Stone is playing with the mythic figure that we know as Jim Morrison. The Doors tries to show both sides: the mythic persona and the real man drowning in fame, drugs and alcohol. Stone hints at this transformation when Morrison does the famous photo shoot that has been immortalized in posters and in the pages of glossy rock magazines like Rolling Stone. Morrison is drunk on alcohol and one might argue his own fame. He begins to believe in his own image and the photographer (Mimi Rogers) only coaxes him on when she says, “Forget the Doors. You’re the one they want. You are the Doors.” It is at this point in the film that Morrison is no longer an artist or a poet, but a commodity to be used up by everyone: the media and the masses. On Morrison’s rise to the top, everyone wants a piece of him, to capture a little bit of the exhilarating ride. Morrison’s mistake was that he obliged and thought that he could handle it.

We see how drugs and alcohol fuel Morrison’s irrational behavior and he becomes verbally and physically abusive towards Pamela. Anything that was good about Morrison depicted in the film is now gone and all we’re treated to is a series of scenes showing what an asshole he had become and how he had been consumed by his own fame. His bad behavior reaches new heights of ridiculousness during a scene where he and Pamela host a dinner party for their friends and hanger-ons. Stoned out of his mind (and probably drunk), Morrison provokes Pamela who starts throwing food around hysterically and then tries to stab him with a carving knife while he taunts her. Stone sledgehammers the point home by playing “Love Me Two Times” on the soundtrack as if to reinforce Morrison repeatedly cheating on Pamela with other women. If there is anything good that comes from this wildly over-the-top scene it is that it shows how estranged Morrison has become from the rest of his bandmates.

Fortunately, the film has amazingly choreographed concert sequences that repeatedly bring it back from the brink of its own excesses. The New Haven ’68 concert depicts Morrison’s run-in with the law when he was maced in the face backstage by a cop. It’s no longer about the music but the abuse of his power as a lead singer with a microphone to air his grievances. The best concert sequence in the film is the San Francisco ’68 one. Bathed in hellish red light, Morrison whips the crowd into a frenzy. His increasingly desperate performance is juxtaposed with his out of control personal life as he almost traps Pamela in their bedroom closet and proceeds to burn it down, gets in a car accident and is involved in a Wiccan marriage ceremony. We see Morrison in a wonderfully hallucinatory moment channel his Native American Indian spirit as he loses himself in the music. The last shot of this powerful sequence shows Morrison drunk on his own power and fame as much as he’s drunk on alcohol. The expression on Kilmer’s face says it all.

Over the years, directors like Brian De Palma, Martin Scorsese and William Friedkin flirted with directing a Doors biopic. In 1985, Columbia Pictures acquired the rights from the Doors and the Morrison estate to make a film. Producer Sasha Harari wanted Oliver Stone to write the screenplay but never heard back from the filmmaker’s agent. After two unsatisfactory scripts were produced, Imagine Films replaced Columbia. Harari tried contacting Stone again and the director met with the surviving band members. He told them that he wanted to keep a particularly wild scene from one of the early drafts. The group was offended and exercised their right of approval over the director and rejected Stone. By 1989, Mario Kassar and Andy Vajna, who owned Carolco Pictures, acquired the rights to the project and wanted Stone to direct. The Doors had seen Platoon (1986) and were impressed with what Stone had done.

Stone agreed to make The Doors after his next project, Evita (1996). After spending years on it and courting Madonna and later Meryl Streep to play the lead role, the film fell apart over salary negotiations with Streep. Stone quickly moved on to The Doors and went right into pre-production. Guitarist Robby Krieger had always opposed a Doors film until Stone signed on to direct. Stone first heard the Doors when he was a 21-year-old soldier serving in Vietnam. Historically, keyboardist Ray Manzarek had been the biggest advocate of immortalizing the band on film but opposed Stone’s involvement. According to Krieger, “When the Doors broke up Ray had his idea of how the band should be portrayed and John and I had ours.” Manzarek was not happy with the direction Stone wanted to take and refused to give his approval to the film. According to Kyle MacLachlan, “I know that he and Oliver weren’t speaking. I think it was hard for Ray, he being the keeper of the Doors myth for so long.” Manzarek claims that he was not even asked to consult on the film and if he had his way wanted it to be about four members equally rather than the focus being on Morrison. Stone claims that he repeatedly tried to get the keyboardist involved, but “all he did was rave and shout. He went on for three hours about his point of view ... I didn’t want Ray to be dominant, but Ray thought he knew better than anybody else.”

While researching the film, Stone read through transcripts of interviews with over 100 people. The cast was expected to get educated about 1960s culture and literature. Stone wrote his own script in the summer of 1989. He said, “The Doors script was always problematic. Even when we shot, but the music helped fuse it together.” He picked the songs he wanted to use and then wrote “each piece of the movie as a mood to fit that song.” Before filming, Stone and his producers had to negotiate with the three surviving band members, their label Elektra Records, and the parents of Morrison and Pamela Courson. Morrison’s parents would only allow themselves to be depicted in a dream-like flashback sequence at the beginning of the film. The Coursons wanted there to be no suggestion in any way that their daughter caused Morrison’s death. Stone found her parents to be the most difficult to deal with because they wanted Pamela to be “portrayed as an angel.” The Coursons tried to slow the production down by refusing to allow any of Morrison’s later poetry to be used in the film. After he died, Pamela got the rights to his poetry and when she died, her parents got the rights. Legendary concert promoter Bill Graham, who promoted Doors concerts in San Francisco and New York in the ‘60s, played a key role in negotiations.

When Stone began talking about the project as far back as 1986, he had Kilmer in mind to play Morrison, impressed by his work in the Ron Howard fantasy film Willow (1988). However, during this time actors ranging from John Travolta to Richard Gere to Tom Cruise and the lead singers from INXS and U2 were considered for the part. Stone auditioned nearly 200 actors to play Morrison in 1989. In his favor, Kilmer had the same kind of singing voice as Morrison and to convince Stone that he was right for the role he spent thousands of dollars of his own money to make his own eight-minute video, singing and looking like the Lizard King at various stages of his life. When the Doors heard Kilmer singing they couldn’t tell if it was him or Morrison’s voice. Once he got the part, he lost weight and spent six months rehearsing Doors songs every day. Kilmer learned 50 songs, 15 of which are actively performing in the film. He also spent hundreds of hours with record producer Paul Rothchild who told him, “anecdotes, stories, tragic moments, humorous moments, how Jim thought, what were my interpretation of Jim’s lyrics,” he said. He also took Kilmer into the studio and helped him with “some pronunciations, idiomatic things that Jim would do that made the song sound like Jim.” The actor also met with Krieger and Densmore but Manzarek refused to talk to him.

Stone auditioned approximately 60 actresses for the role of Pamela Courson. The part required nudity and the script featured some wild sex scenes which generated a fair amount of controversy. Casting director Risa Bramon Garcia felt that Patricia Arquette auditioned very well and should have gotten the part. However, Meg Ryan was cast and to prepare for the role, she talked to the Coursons and people that knew Pamela and encountered several conflicting views of her. Before doing the film, Ryan was not at all familiar with Morrison and “liked a few songs.” She had trouble relating to the culture of the ‘60s and said, “I had to reexamine all my beliefs about it in order to do this movie.”

Stone originally hired Paula Abdul to choreograph the film’s concert scenes but dropped out because she did not understand Morrison’s on-stage actions and was not familiar with the time period. She recommended Bill and Jacqui Landrum. They watched hours of concert footage before working with Kilmer. They got him to loosen up his upper body with dance exercises and jumping routines to develop his stamina for the demanding concert scenes. During them, he did the actual singing and Stone used the Doors’ master tapes without Morrison’s lead vocals to avoid lip-synching. Kilmer’s endurance was put to the test during these sequences, with each one often taking several days to film. Stone said, “his voice would start to deteriorate after two or three takes. We had to take that into consideration.” One sequence, filmed inside the Whisky a Go Go was harder than the others due to all the smoke and the sweat, a result of the body heat and intense camera lights. For five days Kilmer performed “The End” and after the 24th take, Stone got what he wanted and the actor was left totally exhausted.

With a budget of $32 million, The Doors was filmed over 13 weeks predominantly in and around Los Angeles. Krieger acted as a technical adviser on the film and this mainly involved showing his cinematic alter ego Frank Whaley where to put his fingers on the fretboard. Densmore also acted as a consultant, tutoring Kevin Dillon who played him in the film. Controversy arose during principal photography when a memo linked to Kilmer circulated to cast and crew members listing rules of how the actor was to be treated for the duration of filming. These included people being forbidden to approach him on the set without good reason, not to address him by his own name while he was in character, and no one could “stare” at him on the set. Understandably upset, Stone contacted Kilmer’s agent and the actor claimed it was all a huge misunderstanding and that the memo was for his own people and not the film crew.

Not surprisingly, The Doors received mixed to negative reviews from critics. Roger Ebert gave the film two-and-a-half stars out of four and wrote, “The experience of watching The Doors is not always very pleasant. There are the songs, of course, and some electrifying concert moments, but mostly there is the mournful, self-pitying descent of this young man into selfish and boring stupor … The last hour of the film, in particular, is a dirge of wretched excess, of drunken would-be orgies and obnoxious behavior.” In her review for The New York Times, Caryn James wrote, “At its best, the film's haunted Doors music and visceral look creates the sense of being in some hypnotic trance. But by the end, audiences may feel they have been beaten over the head with a stick for two hours.” Time magazine’s Richard Corliss wrote, “His movies make people edgy, and that's a good thing. But this time Stone is a symptom of the disease he would chart … Maybe it was fun to bathe in decadence back then. But this is no time to wallow in that mire.” In his review for the Washington Post, Hal Hinson wrote, “Amid all this trippy incoherence, the performances are almost irrelevant. Kilmer does a noteworthy impersonation of the singer, especially onstage, where he gets Morrison's self-absorption. He gets his coiled explosiveness too, but the element of danger in Morrison is missing.”

The Chicago Reader’s Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote, “Some of the effects are arresting, and apart from some unfortunate attempts to ‘re-create’ Ed Sullivan, Andy Warhol, and Nico, the movie does a pretty good job with period ambience. But it's a long haul waiting for the hero to keel over.” Famous conservative pundit George Will not only attacked Morrison, calling him, “not particularly interesting” and that he “left some embarrassing poetry and a few mediocre rock albums,” but also the film: “for today’s audiences, Stone’s loving re-creation of San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district is just a low-rent Williamsburg, an interesting artifact but no place for a pilgrimage.” However, Entertainment Weekly gave the film a “B” rating and Owen Gleiberman wrote, “As Morrison, Val Kilmer gives a star-making performance. Lolling around in his love beads and black-leather pants, his thick dark mane falling over features that are at once baby-sweet and preternaturally dangerous, Kilmer captures, to an astonishing degree, the hooded, pantherish charisma that made Morrison the most erotically charged pop performer since the early days of Elvis.”

So how did the actual Doors feel about the film? Robby Krieger was impressed with Kilmer’s portrayal of Morrison: “It was really weird. I even called him ‘Jim’ a few times without meaning to.” In his memoirs, John Densmore wrote, “For what it is, I do think Oliver Stone’s vision of Jim Morrison has integrity; however, it is a film about the myth of Jim Morrison.” Ray Manzarek said of the film, “The movie misses out – Oliver Stone blew it ... The movie looks good, sure, but the basic heart is stone cold.”

Stone also uses several film techniques like special lighting to create a red hue over everything and a swaying, chaotic camera to create an off-kilter hallucinogenic world that he would later perfect in Natural Born Killers (1994). This effect gives the film the overall effect of a peyote experience without actually taking drugs. The Doors also captures the madness and paranoia of the era with quick edits of the horrors of Vietnam, and the Robert F. Kenney assassination juxtaposed with the belligerent cops at every concert, and the rampant drug use associated with this scene. One band member says during the film that he took drugs to expand his mind not to escape as Morrison did. As the scenes of Morrison’s excessive behavior pile up, a feeling of exhaustion sets in as it begins to be all too much which, I guess, is kind of how Morrison felt towards the end. A feeling of burn out takes over and the end of the film can’t come soon enough. The experience of watching The Doors leaves one drained and you really feel like you’ve been somewhere and experienced something.

The Doors is a potent reminder of the self-destructive power of rock stars that the media manipulates and thrives on. At one point in the film during a press conference, Morrison says, “I believe in excess,” and in doing so underlines the whole thesis of the film. The Doors is a film about excess on many levels: on a individual level with Morrison himself, on a national level with thousands of fans going crazy at the mere sight of the singer, and on a personal level with Stone’s own preoccupations permeating throughout. The Doors also examines the seductive power of the cult of personality, the god-like status to which people like Morrison or someone like Kurt Cobain are elevated to and the inevitable crash that follows when they can’t handle the responsibility. Morrison represents a generation trying to escape the pain of a crazy world. Like Cobain, Morrison wanted to ultimately be seen as an artist, but was treated in life and after his death like a commodity (Morrison was once referred to as the “ultimate Barbie doll.”). Both men were consumed by the very thing that created them: the media. They also ended their own lives, Cobain via suicide and Morrison through alcohol abuse. The Doors is a powerful study of excesses of every kind: sex, drugs, alcohol, and fame on an individual and on a society.

One should look at The Doors much like Stone’s subsequent film JFK (1992), as a mythical take on historical figures and events and not as documentary-like authenticity. I find The Doors to be a big, bloated, fascinating mess of a film that reflects the tumultuous times of the ‘60s. Despite the miscasting of a few roles and the rather one-sided view we get of Morrison, Stone’s film is a beautifully-shot acid trip through the ‘60s with some of the best choreographed live concert sequences every recreated on film. Best of all, it brought the Doors’ music back into the mainstream, reminded everyone what a brilliant band they were, and how much they influenced and reflected their times.

The film starts off with Morrison (Val Kilmer) recording An American Prayer and reciting lines that rather nicely apply to the beginning of this biopic. Then, Stone takes us back to New Mexico, 1949 when the singer was just a boy. As Robert Richardson’s camera floats over desolate, sun-drenched desert, the first atmospheric strains of “Riders on the Storm” plays over the soundtrack. Right from the get-go, Stone establishes the mythical approach he plans to adopt for the film by recreating a popular story told by Morrison that as a young boy his family passed by a car accident involving an elderly Native American Indian. As the story goes, at the moment when he died, his spirit left his body and went into the young Morrison. The story was meant to explain Morrison’s fascination with shamanism and mysticism.

We quickly jump to Venice Beach, 1965 where Morrison is attending film school at UCLA along with Ray Manzarek (Kyle MacLachlan). He also meets Pamela Courson (Meg Ryan), who would go on to become the great love of his life, and they quickly become romantically involved. The appearance of these two people exposes early on one of the film’s flaws – the miscasting of Kyle MacLachlan as Manzarek and Meg Ryan as Pamela. Whereas from his first appearance on-screen, you instantly accept Val Kilmer as Morrison, MacLachlan comes across as too stiff and the dialogue doesn’t sound natural coming out of his mouth. Not to mention, his wig is a distraction. With Ryan, it is her identification with romantic comedies like When Harry Met Sally... (1989) and Joe Versus the Volcano (1990) that makes it so hard to believe her as a free-spirited flower child that eventually transforms into a promiscuous drug user. In scenes where Pamela is supposed to come across as naive, Ryan conveys a clueless vacancy. It’s too bad because she would go on to demonstrate an ability to tap into a darker side with Prelude to a Kiss (1992) and more significantly with the little-seen Flesh and Bone (1993). However, with The Doors, she is clearly out of her comfort zone and it is glaringly obvious.

From there we go to that fateful day when Morrison sang some of the lyrics to “Moonlight Drive” to Manzarek and they proposed starting a band, coming up with the name, the Doors. Stone jumps to the band now with drummer John Densmore (Kevin Dillon) and guitarist Robby Krieger (Frank Whaley) rehearsing “Break on Through (To the Other Side).” This is a really strong scene as it shows the genesis for their biggest song, “Light My Fire” and Stone makes a point of showing that Morrison didn’t write all of their songs. Stone also shows how they all contributed to the song’s evolution that resulted in the classic it became. I also like how we see the Doors starting out, playing a small dive on the Sunset Strip called London Fog. Morrison is still so shy on stage that he can’t face the audience. This is the film at its best, showing the band creating music and in action, performing live.

It goes without saying that The Doors truly comes to life during the concert scenes as all the theatrical stage lighting and dynamic camera movements showcases Richardson’s skill as one of the best cinematographers ever to get behind the camera. The warm colors he uses in the London Fog scenes conveys an intimacy representative of the small venue and symbolizes a band still learning their chops, both musically and how they perform in a live setting. Richardson really gets a chance to cut loose in the sequence where the band go out into the desert and take peyote. He employs all sorts of trippy effects and also creates some stunningly beautiful shots, like that of a blue sky populated by all kinds of fragmented clouds or a pan across a rocky formation with shadows creeping upwards, animated via time lapse photography.