The Lonely Guy (1984), starring Steve Martin and Charles Grodin, is part of a popular

subgenre of the romantic comedy with sad sack protagonists unlucky in and often

looking for love such as Woody Allen’s Annie

Hall (1977) and Albert Brooks’ Modern

Romance (1981) with the female equivalent in movies like Bridget Jones’s Diary (2001) and Someone Like You (2001). These movies

often feature socially awkward protagonists fumbling their way through

unsuccessful relationships. The Lonely

Guy fancies itself as a grandiose cinematic statement on the subgenre right

down to the mock-epic-style opening that playfully references 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968).

Larry Hubbard (Martin) is a

successful greeting card writer living in New York City. He comes home one day

to find his girlfriend in bed with another man and seems completely oblivious

to it all in an amusing bit where he carries on with his daily routine as if

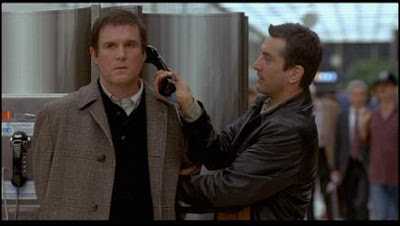

nothing is wrong. Kicked to curb, Larry wanders the streets until he sits on a

park bench and meets experienced “lonely guy” Warren Evans (Grodin) whose

girlfriend just left him for a guy robbing her apartment (“It’s probably for

the best. She was really starting to let herself go,” he deadpans.).

Warren gives Larry a lot of

helpful advice, like avoiding wealthy neighborhoods to live in because they

have high crime rates (he even sees a man thrown off a building and another guy

shot on the sidewalk in front of him!). These early scenes between Steve Martin

and Charles Grodin are among the strongest of the movie as the former’s

optimism clashes hilariously with the latter’s pessimism.

Larry soon discovers that

there are all kinds of other lonely, single guys like him out there and they

need advice like he did and so he decides to write a book entitled, A Guide for the Lonely Guy. It becomes

hugely successful and Larry finds himself not so lonely any more. He even tries

to pick up a woman at a bar by telling her that he’s looking for a real

relationship while she admits that she just wants to have sex. As if on cue,

Warren shows up and asks Larry, “Ever think about getting a dog?”

This scene demonstrates how The Lonely Guy deftly juggles satire

with keen observations on human behavior. Everything is heightened for comedic

effect reminiscent of the Zucker Abrams Zucker movies only not quite as zany.

In some respects, this movie, with its self-reflexive voiceover narration and

breaking of the fourth wall, feels like a warm-up for Martin’s comedic opus L.A. Story (1991), which manages to

balance satire with poignant observations about relationships much more

successfully.

Larry meets Iris (Judith Ivey), an attractive woman he keeps running into but is unable to make it work

because the timing isn’t right. They have an on-again-off-again relationship

that plays out over the course of the movie.

Martin manages to

effortlessly tread a fine comedic line between hapless doormat and hopeless

romantic. The problem with a lot of romantic comedies is that they’re populated

by impossibly good-looking people that would never have a problem finding love

and while he is a handsome guy Martin is able to convey the awkwardness of

someone lacking confidence – that makes him a believable lonely guy.

Grodin plays Warren as the

ultimate dweeb who refers to his plants as “guys.” In the 1980s, he excelled at

playing uptight, nebbish characters (Midnight

Run) and this is one of the best takes on this type. In a movie with many

outrageous gags and set pieces, he wisely underplays, delivering a less is more

performance that is quite funny. The best scenes in the movie are between him

and Martin. They play well off each other and it’s a shame they didn’t do more

movies together.

Neil Simon adapted Bruce Jay Friedman’s book, The Lonely Guy’s Book of

Life and then Jay Friedman and Stan Daniels, known for their work on

television sitcoms like The Mary Tyler

Moore Show and Taxi, wrote the

screenplay. The project was a challenging change of pace for them as the latter

said, “We were used to writing about real people and real problems – in other

words, just straightforward realistic comedy. The Lonely Guy is a stylized way of getting at reality.”

Principal photography began

in spring of 1983 at Universal Studios’ famous New York City backlot on Stage

28 with Larry and Warren’s apartments built on the same soundstage. Incredibly,

a life-sized scale replica of the Manhattan Bridge was constructed, standing

eight feet in the air and was 44-feet wide, taking four weeks to build. In

addition, actual location shooting took place in Los Angeles and for three

weeks in New York.

The Lonely Guy was savaged by critics with Roger Ebert giving it one-and-a-half out of

four stars and writing, “The Lonely Guy

is the kind of movie that seems to have been made to play in empty theaters on

overcast January afternoons.” In her review for The New York Times, Janet Maslin wrote, “Whenever the film tries

for sprightliness, it stumbles. When it gives in to the basic misery of Larry

and his situation, though, it begins to make some sort of morose comic sense.”

Pauline Kael felt that is had “some wonderful gags and a lot of other good

ideas for gags, but it was directed by Arthur Hiller, who is the opposite of a

perfectionist, and it makes you feel as if you were watching television.” The Washington Post’s Gary Arnold wrote,

“Nevertheless, despite the flailing around, the picture fitfully accumulates a

handful of modest highlights and silly brainstorms. They may seem sufficient to

justify the trouble, especially if you extend Martin & Co. the courtesy of

not expecting a classic.” Even Martin wasn’t too crazy with the end result. He

didn’t like Larry and felt that as a character he was “too weak. I realized I

played too nebbishy. That’s what was written, but it’s not a character I

especially want to play anymore.”

Even though the situations

Larry finds himself in are heightened for comedic effect, The Lonely Guy does capture the single guy mindset quite well – the

desperation and the rationalization that a lot of men experience as they try to

find that special someone. Ultimately, the movie suggests that you have to be

willing to put yourself out there if you want to meet someone and that takes

courage as you run the risk of being rejected. There’s something to be said

about making an attempt and the movie champions this approach albeit in a

satirical way. If The Lonely Guy is

remembered at all its as a commercial and critical failure that not even its

star liked but I think he, Kael and other film critics have been too hard on

this trifle of a movie that is funny and features a stand-out performance by

Charles Grodin.

SOURCES

Pollock, Dale. “Steve

Martin: A Wild and Serious Guy.” Los Angeles Times. September 16, 1984.

The Lonely Guy Production Notes. 1984.