After the phenomenal success

of Annie Hall (1977), Woody Allen

confounded the expectations of his critics and fans with Interiors (1978), which saw him doing his best Ingmar Bergman

impression. It was his first dramatic film and while critical reaction was

mostly positive, it hardly set the box office on fire. With Manhattan (1979), Allen returned to

familiar material – the witty romantic comedy – with what many consider his

masterpiece but a film that he famously felt was so bad that he offered to make

another one for the studio for free if they agreed to not release it.

Thankfully, they didn’t listen to him and the end result is one of the greatest

cinematic love letters to New York City ever committed to film while also

taking an entertaining and insightful look at the love lives of a handful of

its inhabitants.

Allen establishes his

ambitious intentions right from the start with a grandiose montage of the city

scored to George Gershwin and photographed in gorgeous black and white by cinematographer

Gordon Willis. The opening voiceover narration that plays over this footage

works on several levels. On the surface, it is Isaac Davis (Allen) trying to

start his novel but rejecting his multiple attempts because the tone is too

corny, too preachy or too angry until he comes up with an introduction that

makes him sound good and he ends it with the immortal words, “New York was his

town and it always would be.” This opening monologue plays over and often

comments on images of New York bustling with life from various neighborhoods

and all kinds of people from all social strata. That last line would also be

prophetic words as Allen’s name has become synonymous with the city he’s

immortalized on film so many times.

This is the Big Apple as

seen through Allen’s eyes as he presents his unique world populated by a rarefied

social strata of well-educated, neurotic people entangled in messy

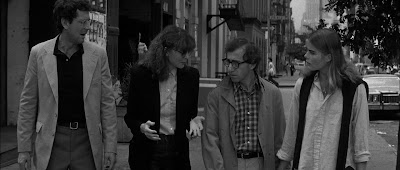

relationships with each other. Still stinging from a bitter divorce, television

comedy writer Isaac (Allen) is now dating Tracy (Mariel Hemingway), a

17-year-old girl (“I’m dating a girl who does homework.”). His best friend Yale

(Michael Murphy), a college professor, is having an affair with a journalist

named Mary (Diane Keaton). We meet Isaac and his narcissistic friends at

Elaine’s, a then-trendy restaurant on the Upper East Side, which Allen uses to

set-up their relationships.

Isaac and Yale’s lives are a

mess with the former writing for a television show he loathes and the latter

trying to finish a book and start up a magazine. The last thing they need is to

complicate their romantic lives. Isaac realizes that Tracy is too young for him

(“You should think of me as a detour on the highway of life.”) and gets

involved with Mary after Yale introduces them. At first, Isaac and Mary can’t

stand each other, arguing over an art exhibit and several artists she feels are

overrated but he thinks are great (i.e. Lenny Bruce, Vincent Van Gogh, Ingmar

Bergman, and so on). Mary is everything that Tracy is not – worldly and not

afraid to speak her mind (at one point, he describes her way with words as

“pithy yet degenerate.”). Isaac is instantly put-off by this because she isn’t

easily controllable like Tracy. Mary is not afraid to challenge Isaac, which is

what ultimately appeals to him.

He breaks up with Tracy and

starts up with Mary. She is more his equal in every way and it makes sense that

they get together. She is brutally honest in her assessment of his and her own

shortcomings and he likes that. They connect while spending a night into early

morning talking through the streets of the city, walking her dog and then

getting food at a local diner to the dreamy strains of “Someone to Watch Over

Me.” This wonderful scene culminates with the iconic shot of Isaac and Mary

sitting on a bench in front of the Queensboro Bridge at dawn, which

was also used in the film’s poster.

Woody Allen and Diane Keaton

continue their undeniable on-screen chemistry as they play so well off each

other. She is allowed to tone down the more exaggerated comedic gestures she

used in Annie Hall to create a more

nuanced character in Manhattan. Initially,

Mary comes across as abrasive but once she’s alone with Isaac her tough

exterior softens and we realize that they have a lot in common. He makes her

laugh and we can see the attraction between them growing. This complicates

things because it prompts Isaac to breakup with Tracy to be with Mary who

breaks up with Yale, which puts a strain on his friendship with Isaac.

Keaton displays a wonderful

level of vulnerability over the course of the film as Mary feels comfortable

enough around Isaac to share her insecurities, admitting that she gets involved

with dominating men. Keaton’s Mary is a wonderful mix of smarts, beauty and

humor – it’s no wonder that both Isaac and Yale are in love with her. The

actress is also good during the more serious scenes, like when Mary and Yale

breakup and then later she talks to Isaac about it. Keaton convincingly conveys

how upset her character is even if ultimately it is the best thing as it opens

the door for her and Isaac to get together.

Woody Allen essentially

plays himself, which sounds like a backhanded compliment when it actually isn’t

as he bounces back and forth between witty one-liners and neurotic hand

wringing. Allen is more than a neurotic joke machine as Isaac wrestles with his

own moral dilemmas – his love for Tracy, even though he knows she’s too young

for him, and his attraction to Mary who is much more compatible. It’s hard not

to see Isaac’s relationship with the much younger Tracy eerily foreshadowing

Allen’s real-life relationship with his young adopted daughter Soon-Yin Previn

and this gives the on-screen relationship between the characters an added

uncomfortable vibe at times – one that already exists with the vast age

difference and Isaac initially making light of it.

Mariel Hemingway is

excellent as Tracy, the young woman that adores Isaac and is able to hold her

own with him and his pseudo-intellectual friends. Ironically, she is the most

mature character in the film and also the one that is the nicest while also

being the youngest. Perhaps she hasn’t lived long enough to become jaded and

cynical like Isaac and his friends. There is still an innocence to her and

perhaps this is what draws Isaac to Tracy. The actress displays an impressive

range of emotions, culminating in the heartbreaking scene where Isaac breaks up

with Tracy. The hurt her character feels in this scene is almost tangible and

we really empathize with her.

While Manhattan features an abundance of Allen’s funny one-liners, the

screenplay he co-wrote with Marshall Brickman tempers it somewhat with the

characters’ messy personal lives, like the resentment Isaac feels towards his

ex-wife (Meryl Streep) for leaving him for another woman, or Yale cheating on

his perfectly lovely wife (Anne Byrne) with Mary. Allen expertly shifts gears

from comedy to drama from scene to scene and sometimes even within the same

scene.

Allen takes us through a

guided tour through the city with key scenes taking place at famous

establishments, like Elaine’s and the Russian Tea Room, or tourist spots like

the Hayden Planetarium, in such a way that New York becomes a character unto

itself. Willis’ gorgeously textured black and white cinematography not only

evokes the classic Hollywood cinema that Allen loves so much but at the time of

Manhattan’s release black and white

film stock was rarely used in popular contemporary cinema. Whether they meant

to or not, Allen and Willis were making a bold artistic statement with this

choice, which elevated the film from being just another romantic comedy to

something more. For example, there is a fantastic scene in the aforementioned

Planetarium where Isaac and Mary walk through the exhibits, including a Lunar

landscape and Saturn looming large in the background in another room while the

two characters appear almost entirely in silhouette. Sadly, several of the

places the characters frequent no longer exist making Manhattan a historical document of sorts.

Woody Allen first started

talking about the origins of Manhattan

over dinners with cinematographer Gordon Willis while they were filming Interiors. Allen wanted to make “an

intimate romantic picture” in a widescreen aspect ratio and do it in black and

white because “that had a Manhattan feel to it.” At the time, he was listening

to recordings of Gershwin overtures and thought of setting a scene to that

music.

Allen began working on a

story with regular collaborator Marshall Brickman (Annie Hall). They would talk about potential ideas, like, “Wouldn’t

it be funny if I liked this really young girl and if Keaton was this major

pseudo-intellectual?” Brickman would envision a scene and ad-lib it. Allen

would do the same and they’d go back and forth. The two men ran into a roadblock

when neither of them could figure out the film’s climax until during filming

Brickman’s wife told him they needed a scene where Isaac confronts Yale, which

became the climactic scene in the latter’s classroom.

Originally, the opening

montage scene was going to be scored to “I Can’t Get Started” by Bunny Berigan

because that song played several times every night at Elaine’s on the jukebox.

During post-production, editor Susan E. Morse suggested they use “Rhapsody in

Blue” instead. Allen agreed and decided to use Gershwin music throughout. When Manhattan was finished, he was so

disappointed with the film that he asked United Pictures not to release it: “I

wanted to offer them to make one free movie, if they would just throw it away.”

Fortunately, they declined Allen’s offer.

Manhattan received

mostly positive reviews from mainstream critics at the time. Roger Ebert gave

the film three-and-a-half out of four stars and wrote, “The relationships

aren’t really the point of the movie: It’s more about what people say during

relationships – or, to put it more bluntly, it’s about how people lie

technically telling the truth.” In his review for The New York Times, Vincent Canby wrote, “The movie is full of

moments that are uproariously funny and others that are sometimes shattering

for the degree in which they evoke civilized desolation.” The Village Voice’s Andrew Sarris said of

the film that it “materialized out of the void as the one truly great American

films of the ‘70s.” In her review for The

New Yorker, Pauline Kael wrote, “What man in his forties but Woody Allen

could pass off a predilection for teenagers as a quest for true values?” The Washington Post’s Gary Arnold wrote,

“There’s no opportunity to heap condescending abuse on the phonies and sellouts

decorating the Hollywood landscape. The result appears to be a more authentic

and magnanimous comic perception of human vanity and foolhardiness.” In recent

years, critics like J. Hoberman offered their assessment of the film when he

wrote, “What’s most authentic about Manhattan

is its fantasy. The New York City that Woody so tediously defended in Annie Hall was in crisis. And so he

imagined an improved version. More than that, he cast this shining city in the

form of those movies that he might have seen as a child in Coney Island—freeing

the visions that he sensed to be locked up in the silver screen.”

After the failure of Interiors, Manhattan could be seen as Allen’s return to the same formula that

made Annie Hall a success. While

there are similarities between the two films, Manhattan showed how much he had

matured as a filmmaker by injecting more dramatic weight without upsetting the

overall balance of the film. He wasn’t simply content to make an entertaining

romantic comedy. Manhattan not only

expressed his feelings for New York but also his views on relationships. It is

arguably Allen’s most complete expression of his unique cinematic worldview – highly

educated people with very little common sense when it comes to their personal

lives, making bad decisions even when they realize it. But like the rest of us,

they keep on trying, hoping that the next relationship is the one. He continues

to explore it with numerous variations, such as locations, time periods, but

they can be traced back to Annie Hall

and Manhattan.

Ultimately, Manhattan is about figuring out what you

want in life and going for it. Isaac doesn’t do this until late in the film

during a classic scene where he lists the things that make life worth living

for him and in doing so achieves an epiphany. The film ends on a bit of

ambiguous note as we are left wondering that the woman he picked was the right

one and if so, how long the relationship will last. In a way, it is cinematic

litmus test for the viewer – if you’re an optimist, the ending is hopeful and

if you’re a pessimist, it is bittersweet. In other words, this scene conveys

the same uncertainty that goes with relationships that the rest of us

experience. That being said, I think Tracy sums it up best when she tells

Isaac, “You have to have a little faith in people.”

SOURCES

Bjorkman, Stig. Woody Allen on Woody Allen. Grove Press.

1993.

Lax, Eric. Conversations with Woody Allen. Alfred

A. Knopf. 2007.